by Carl R. Tannenbaum, Ryan James Boyle, Vaibhav Tandon, Northern Trust

Governmental instability is not a new experience for Italy; the country has had 64 governments since the end of World War II. In the 1970s, Italians were terrorized by the Brigate Rosse, a leftist group that killed a former prime minister and sought to remove Italy from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. More recently, former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi (whose appetite for vice was exceeded only by his appetite for power) was convicted of tax fraud and banned from holding office.

In light of that history, the drama that unfolded earlier this week should not be viewed as altogether unusual. On Monday, Italian President Sergio Mattarella prevented a prospective coalition from forming a government, as is his right under the constitution. But the reason for the denial—the potential that Italy would drop the euro—raised an uncomfortable issue that many thought had been closed.

The conditions that led to Monday’s imbroglio are not unique to Italy. The government of Spain is under renewed stress as its economy struggles to sustain momentum. The underlying issues in Europe’s periphery require a broad remedy. But the dissolution of the euro is a very remote possibility.

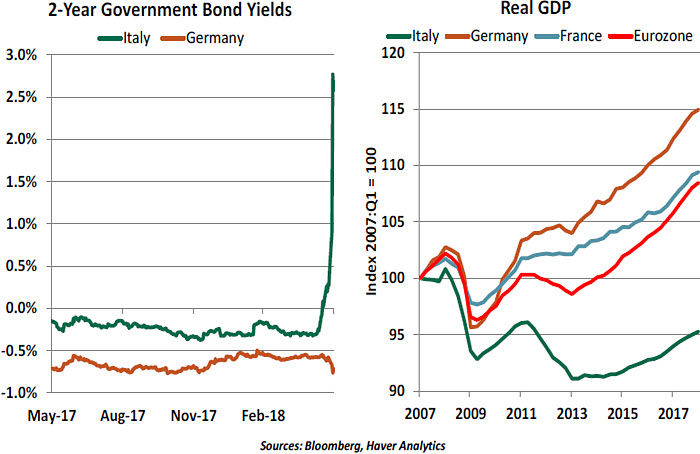

To be sure, the governance crisis in Italy came at an unfortunate time. The eurozone has been riding a nice wave of economic growth and market outperformance. Unemployment has been falling, and reform efforts were back on the table. But first-quarter results were soft, and recent headlines put a dent in investor confidence. Markets reacted angrily to Italy’s impasse, punishing Italian bonds and the euro.

While headline outcomes for the eurozone have been encouraging, conditions beneath the surface are far from perfect. Performance among member nations has been uneven; Germany has prospered, while Italy has foundered. Italy’s real gross domestic product (GDP) has yet to surpass its pre-crisis high, and its unemployment rate of 11% is one of the highest in the euro area.

Italy’s banks remain troubled, almost a decade after the onset of the financial crisis. The failure to resolve bad debts created by the recession (authorities preferred a strategy referred to as “delay and pray”) has left the country’s financial institutions poorly positioned to support economic activity. The close relationship between some Italian

Italy’s banks remain troubled, almost a decade after the onset of the financial crisis. The failure to resolve bad debts created by the recession (authorities preferred a strategy referred to as “delay and pray”) has left the country’s financial institutions poorly positioned to support economic activity. The close relationship between some Italian

lenders and their government has delayed the kind of financial rehabilitation that provided a foundation for recovery in other countries.

The lingering malaise in Italy and other Mediterranean countries provides fertile ground for populism. The movement has different forms in different places, but its supporters are united by their antipathy toward trade, immigration and multinational organizations like the European Union. Elections last year threatened to create a populist wave, but outcomes in the Netherlands, France and Germany produced conventional leaders. Markets breathed a sigh of relief.

But anti-establishment parties garnered substantial support and have a growing voice in European affairs. Until and unless the root causes of discontent are addressed, populism will remain a significant force in regional and global politics.

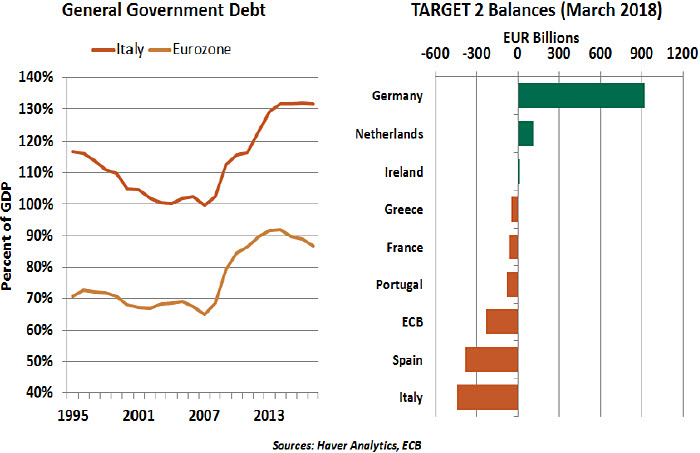

Italy is especially vulnerable, given its political history and the crushing weight of the national debt. Government borrowing totals more than 130% of GDP, and Italy’s central bank has a substantial deficit to its eurozone counterparts through the eurozone’s payment system (known as “TARGET2”). There is no clear path to bringing either situation under control.

The euro has been described as a marriage with no potential for divorce. Procedural steps for a departure do not exist. But Paolo Savona, the gentleman who was originally designated to become Italy’s next finance minister, had apparently developed a playbook to achieve separation.

One wonders if that playbook includes the wide range of adverse consequences that would ensue from such a step. There would almost certainly be a default on Italian debt and stress on the eurozone payment system. Italian banks would be cut off from international funding and capital markets, leading to widespread failures. The new lira would be a weak currency; while that would promote Italian exports, most economists anticipate that negative effects would dwarf this benefit. The Italian economy could be in ruins for quite some time.

Syriza, the Greek populist party, was elected in 2015 on a platform of economic confrontation with Germany and the eurozone more generally. But its leaders were forced to capitulate after the realities of international finance became painfully apparent. Italy is not Greece, for a number of reasons. But the lesson is instructive nonetheless. Once you peer over the cliff, you may decide not to jump.

And that may be what motivated a settlement in Italy at the end of the week. The populist coalition agreed to appoint a more conventional finance minister, who is (at least outwardly) more supportive of remaining in the eurozone. The new government was approved on Thursday. Markets calmed, but will have to await the direction that Italy’s new

And that may be what motivated a settlement in Italy at the end of the week. The populist coalition agreed to appoint a more conventional finance minister, who is (at least outwardly) more supportive of remaining in the eurozone. The new government was approved on Thursday. Markets calmed, but will have to await the direction that Italy’s new

leadership chooses.

It will be very interesting to see what comments Mario Draghi, president of the European Central Bank (ECB), offers on this subject after the next ECB meeting on June 14. The ECB had dropped a reference to downside risks in its official statement and seemed on track to end its asset purchase program before the end of the year. But renewed uncertainty in Italy may extend the effort by some months. And Draghi must avoid appearing to be overly partisan.

It has been a volatile few days, and more may follow. The Italian flair for the dramatic could keep the situation in the headlines for some time. But eurozone leaders have shown the will and the capacity to defend their common currency. And if an existential threat arises, we believe that it will be dealt with effectively.

Help Wanted: Entrepreneurs

Entrepreneurship has gained a new level of respect. Founders of successful businesses are regarded as celebrities and even future political leaders. Reality television series like Shark Tank and Dragon’s Den seek to find the next breakaway success. As a field of study, entrepreneurship continues to gain in popularity at business schools. However, actual new business launches in the United States are not growing at the rate that this buzz might lead us to believe.

Business formation is key to growth in a free market economy. New competitors innovate and create the jobs of the future. New businesses are good today, but great tomorrow. And conversely, a slowdown in new business formation today will weigh on the economy indefinitely.

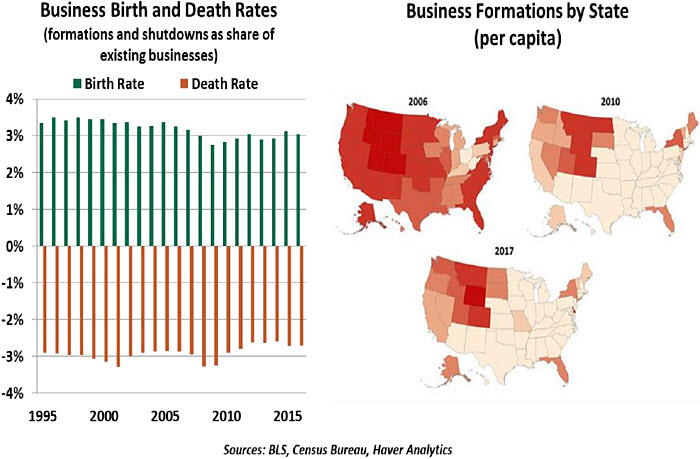

The birth rate of businesses therefore presents some cause for concern. Despite an extended recovery, low costs of credit and ample capital available for investment, new business creation has grown only modestly throughout this economic cycle. As seen below, the “birth rate” of new businesses has remained under the rate seen in past cycles. New research from the U.S. Census Bureau has confirmed that the number of applications to create wage-paying businesses plummeted during the Great Recession and has yet to recover.

The lack of growth is not for lack of business support. The U.S. Small Business Administration subsidizes loans to small businesses. Limited liability laws reduce the personal risk of entrepreneurship. Health insurance requirements, a significant cost of employment, do not apply to firms with fewer than 50 employees.

In the private sector, investors are helping to support business growth by launching incubator programs. Also known as accelerators, budding entrepreneurs bring an idea to an incubator and receive guidance, sometimes with a small sum of seed money, to help build their idea out. Mentors give guidance on crafting business plans, and the entrepreneurs are given resources to build a prototype of their future product or service. Entrepreneurs gain from the guidance they receive, while incubator sponsors get a chance to make an early investment in the next breakout idea.

Once new ideas have demonstrated their potential to become viable businesses, they launch and grow. This is the economically crucial moment at which they may take on employees. New firms that hire people create jobs and broaden the tax base. New businesses serve as a fountain of youth for an economy, creating continued employment

Once new ideas have demonstrated their potential to become viable businesses, they launch and grow. This is the economically crucial moment at which they may take on employees. New firms that hire people create jobs and broaden the tax base. New businesses serve as a fountain of youth for an economy, creating continued employment

opportunities and continually refreshing the competitive playfield. To support the growth of these businesses, small business lenders and private equity funds are continually seeking opportunities to invest in promising young businesses.

Given a substantial support infrastructure and the potential rewards, why isn’t entrepreneurship more common? Market forces are a major impairment. As established competitors grow larger, they exert greater market power. Unless a new entrant can create a new market or find a niche, it is likely to face a large competitor with an established brand and low cost basis.

These large competitors often bring the efficiencies of a national scale to markets that were once local, such as delivery services and grocery stores. They are adept at navigating regulations that can present a challenge to small businesses. We have previously discussed the myriad effects Amazon is having on markets. We cannot quantify how many businesses never launched due to the presence of competitors like Amazon.

The potential entrepreneur’s perspective is worth considering as well. The unemployment rate in the U.S. stands at an 18-year low. The latest Job Openings and Labor Terminations Survey indicated, for the first time in the survey’s existence, that there is a job available for every person who is seeking one. Launching a new venture requires working long hours, begging for funding and shouldering a high risk of failure. Interviewing for a job is a simple and low-risk effort in comparison. It takes fortitude and a strong belief in one’s idea to prefer the risks of entrepreneurship to taking an available position with predictable hours and health insurance.

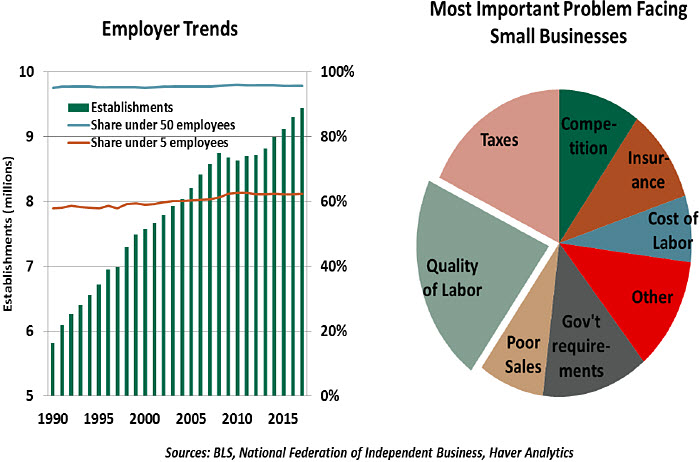

Despite the competitive forces, today’s small business owners are optimistic. The National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) monthly survey of economic trends has, for the past year, shown greater optimism and less uncertainty. When small business owners were asked in the most recent survey to select the greatest challenge they face, the

Despite the competitive forces, today’s small business owners are optimistic. The National Federation of Independent Business (NFIB) monthly survey of economic trends has, for the past year, shown greater optimism and less uncertainty. When small business owners were asked in the most recent survey to select the greatest challenge they face, the

most common answer was a shortage of qualified applicants to fill available jobs.

Small businesses play an important role in every economy. Most businesses that start small stay small – and that’s fine. Across industries, the majority of employers have fewer than 50 employees. As seen above, even as the number of companies in the U.S. has nearly doubled since 1990, the shares with up to five and with fewer than 50 employees have remained steady. While some may have failed and others grown into larger employers, many have found their right size staying small. They are no less valuable to the economy.

High-growth “unicorn” start-ups get a lot of attention but are not the norm. It’s easy to daydream about building an empire after watching a feature-length film about Steve Jobs or Mark Zuckerberg. But for every runaway success, there have been thousands of medical offices, repair services, factories and specialty shops that have collectively sustained millions of jobs. These will continue to form the foundation of our economy, and we applaud efforts to support small business creation.

northerntrust.com

Information is not intended to be and should not be construed as an offer, solicitation or recommendation with respect to any transaction and should not be treated as legal advice, investment advice or tax advice. Under no circumstances should you rely upon this information as a substitute for obtaining specific legal or tax advice from your own professional legal or tax advisors. Information is subject to change based on market or other conditions and is not intended to influence your investment decisions.

Copyright © Northern Trust