by Martin Jaugietis, Russell Investments

At Russell Investments’ year-end all-employee meeting, our Global Chief Investment Officer, Jeff Hussey, reminded the audience that former U.S. Federal Reserve Chair Alan Greenspan made his now famous “irrational exuberance”1 comment about equity market valuations a full three years before the dot-com bubble eventually burst in March 2000 and equity markets sold off heavily. Jeff was alluding to the idea that momentum can be a powerful force in late cycle rallies, with investor psychology likely playing a big part in driving markets higher for longer periods of time than many industry analysts believe possible.

Jeff’s comment prompted a thought in my mind: at Russell Investments, we spend a lot of time demonstrating the quantitative reasons why one might consider a different approach to investing in today’s low-return environment—as quantitative analysis remains a critically important component of any investment decision. However, we believe it’s also important to not overlook the behavioral traits that may be necessary when transitioning to a new approach. Specifically, the ability to weather the next market downturn may require making investment decisions that are uncomfortable, and go against the herd.

Over the next few years, the trick may be to find an investment approach that still meets your near and medium-term investment goals (but may not exceed them), yet has a far higher probability of withstanding a severe market downturn, if and when one occurs. Similar to being the designated driver at a party, or saying no to that second helping of Christmas pudding, avoiding the impetus to capitulate from this more defensive posture will likely require sticking to positions that don’t feel great at the time, but may likely be the best courses of action in order to achieve the outcomes you want in the end.

But why the impetus—the constant urge to jump ship at the possibility of more short-term gain? Why is it so difficult for all of us to adhere to a plan that may very well be in our own best interests?

Enter the theory of behavioral finance.

Decision-making explained

Behavioral finance theory has its roots in the late 1960s and early 1970s, when psychologists attempted to explain the sometimes irrational behavior of humans in making economic decisions. Two of the leading early academics in the field were Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky, who in 1979 presented an idea called prospect theory. In a nutshell, prospect theory contends that people value gains and losses differently, and, as such, will base decisions on perceived gains rather than perceived losses.2

To demonstrate prospect theory in action, Kahneman and Tversky conducted a series of tests in which subjects answered questions that involved making judgments between two monetary decisions associated with prospective losses and gains. The following questions were used in their study:

1. You have $1,000 and you must pick one of the following choices:

- Choice A: You have a 50% chance of gaining $1,000, and a 50% chance of gaining $0

- Choice B: You have a 100% chance of gaining $500

2. You have $2,000 and you must pick one of the following choices:

- Choice A: You have a 50% chance of losing $1,000, and a 50% chance of losing $0

- Choice B: You have a 100% chance of losing $500

Logic suggests that people choosing B would be more risk adverse than those choosing A, and that there might be somewhat of an even distribution of risk-seeking and risk-averse people. However, the results showed that an overwhelming majority of people chose B for question 1 and A for question 2. The investment implication here is that people are willing to settle for a reasonable level of gains (even if they have a reasonable chance of earning more), but are willing to engage in risk-seeking behaviors where they can limit their losses. In other words, losses are weighted more heavily than an equivalent amount of gains.

Relating Kahneman and Tversky’s test to today’s markets, we are likely in an environment presented in question 2—where our portfolios have grown handily over the past nine years since the global financial crisis, and where we are now presented with scenarios that allow us to either:

- 1. Hang onto our existing portfolios and ride the markets a bit more (i.e., the 50% chance of losing $0), but in doing so potentially risk an outsized loss (i.e., the 50% chance of losing $1000); or

- 2. Take a more defensive stance (i.e., 100% chance of losing $500)

To be clear, we’re not suggesting taking the example in question 2 literally, as most often, adopting a more defensive investing stance doesn’t equal negative results. Rather, it typically means that it may result in marginally lower returns if the markets keep climbing, which—like the designated driver, or the person avoiding that second round of pudding—may not feel great at the time, but may likely be a better choice in the long run.

Multi-asset investing: A potential approach to weathering future storms

At Russell Investments, we believe that a dynamic multi-asset investing approach is worth considering today, in light of our concerns about U.S. equity valuations (which have only been this high twice in the past 100 years—in 1929 and 1999). In a multi-asset approach, active tilting decisions are often focused on downside risk protection, versus an approach that uses a static asset allocation and is therefore fully exposed to any market downturn.

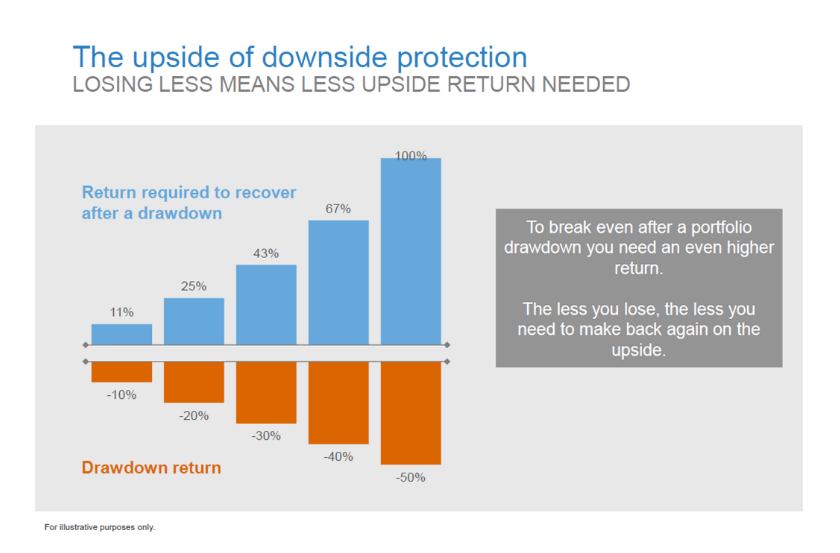

Similar to the results above, prioritizing downside protection over growth may seem like a tough pill to swallow—yet we believe it may be important than chasing the upside. This is because the returns needed to recover after a market downturn increase significantly as losses go deeper. To wit, at the extreme end of things, a 50% drawdown requires a 100% return just to get back to the same dollar level of wealth.3

The recent equity market correction in early February 2018 reminds us of the potential benefits of multi-asset strategies that have the nimbleness to take a more defensive posture when necessary—even if it means only achieving one’s objectives for a while, rather than exceeding them. It might make things more uncomfortable in the short term, but you’ll likely end up in much better shape down the road.

1 Speech by Alan Greenspan to the American Enterprise Institute, December 6, 1996

2 Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky, 1979. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–292

3 This was calculated using mathematical principles of percentages. For example, a 10% loss of $100 is $90. An 11% gain—or an additional $10—is needed to go from $90 to $100. A 20% loss of $100 is $80. A 25% gain—or an additional $20—is needed to go from $80 to $100.

*****

Disclosures

These views are subject to change at any time based upon market or other conditions and are current as of the date at the top of the page.

Investing involves risk and principal loss is possible.

Past performance does not guarantee future performance.

Forecasting represents predictions of market prices and/or volume patterns utilizing varying analytical data. It is not representative of a projection of the stock market, or of any specific investment.

This material is not an offer, solicitation or recommendation to purchase any security. Nothing contained in this material is intended to constitute legal, tax, securities or investment advice, nor an opinion regarding the appropriateness of any investment, nor a solicitation of any type.

The general information contained in this publication should not be acted upon without obtaining specific legal, tax and investment advice from a licensed professional. The information, analysis and opinions expressed herein are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual entity.

Indexes are unmanaged and cannot be invested in directly.

Russell Investments’ ownership is composed of a majority stake held by funds managed by TA Associates with minority stakes held by funds managed by Reverence Capital Partners and Russell Investments’ management.

Frank Russell Company is the owner of the Russell trademarks contained in this material and all trademark rights related to the Russell trademarks, which the members of the Russell Investments group of companies are permitted to use under license from Frank Russell Company. The members of the Russell Investments group of companies are not affiliated in any manner with Frank Russell Company or any entity operating under the “FTSE RUSSELL” brand.

Copyright © Russell Investments Group LLC 2018. All rights reserved.

This material is proprietary and may not be reproduced, transferred, or distributed in any form without prior written permission from Russell Investments. It is delivered on an “as is” basis without warranty.

UNI-11205

Copyright © Russell Investments