by Yusuke Hashimoto, Portfolio Manager—Japan Fixed Income, AllianceBernstein

In January, Japanese government bond (JGB) yields leapt to levels not seen in decades. Investors have long treated Japan’s bond market as a beacon of stability, so the speed and scale of the sell-off—especially in 30- and 40-year bonds—reverberated through global markets. While we don’t think this episode spells crisis, we do think it contains lessons for investors.

Surprise Election Triggers Yield Surge

On January 23, Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi—just three months into her tenure—unexpectedly dissolved the lower house of Parliament and called a surprise snap election for February 8. She also unveiled plans for a substantial fiscal stimulus package and floated a two-year suspension of Japan’s 8% food sales tax, a move that could cost ¥5 trillion annually. This policy shift raised alarms for investors, as Japan already has a high debt-to-GDP ratio of roughly 250%.

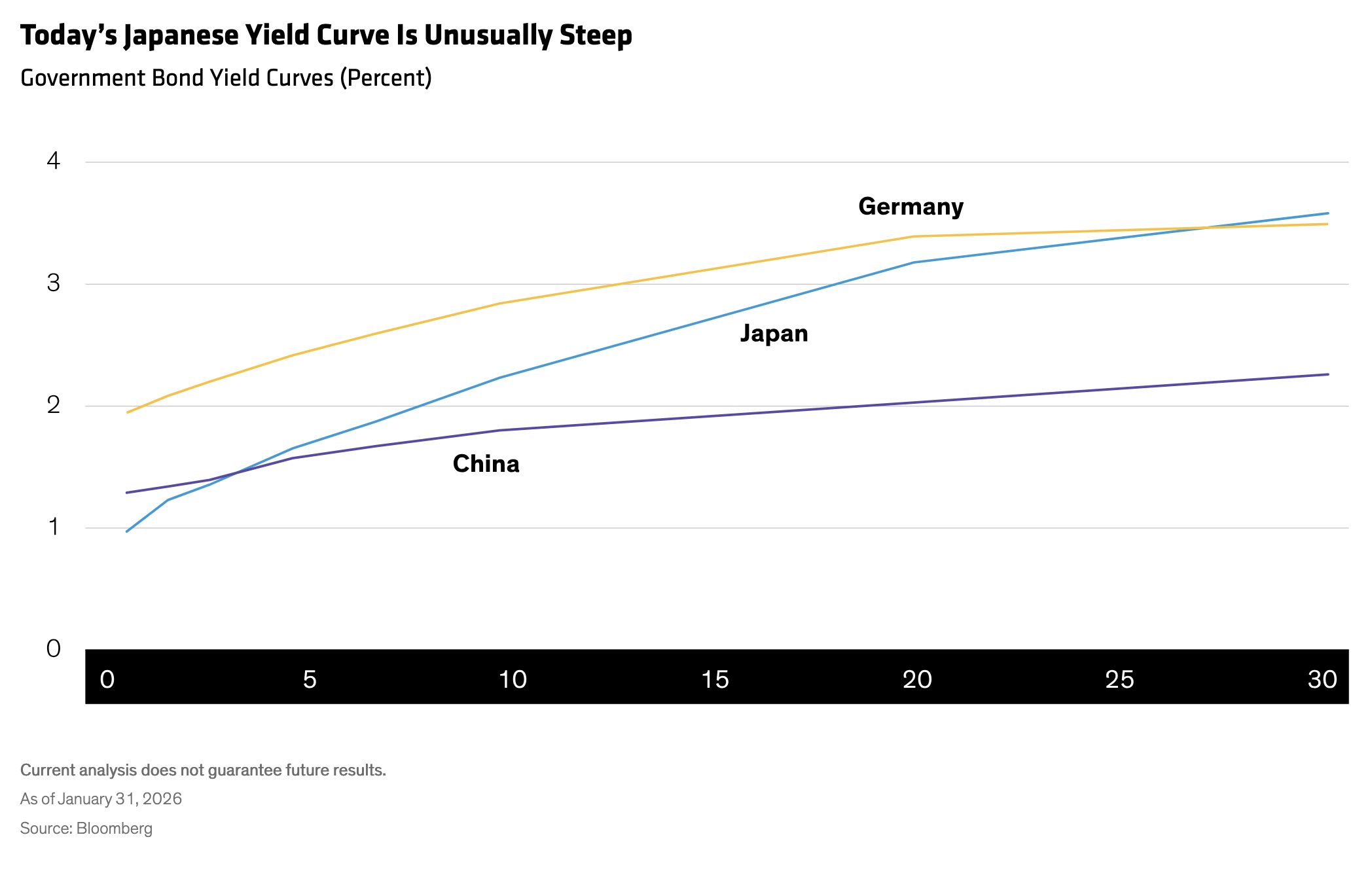

Concerns over fiscal discipline triggered a sharp sell-off in long-dated JGBs. The 30-year yield climbed roughly 20 basis points, while the 40-year yield approached 4%. The JGB yield curve is now unusually steep compared to other developed countries, with 30-year JGBs now higher than German Bunds (Display)—a striking development, given Japan’s long history of yield suppression.

Japan-led volatility reverberated through global bond markets, prompting market-calming comments from US Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent and drawing comparisons in the media to the UK’s Truss-era bond-market stress.

Is Japan Truss-Worthy?

The comparison is tempting but hard to sustain.

The UK’s 2022 crisis under then-Prime Minister Liz Truss involved a spiral of leveraged pension funds, margin calls and forced liquidations that drove rates sharply higher. However, the Truss episode resembled a typical credit-stress event, in that it ultimately flattened the yield curve; in contrast, Japan’s curve has steepened. Further, leveraged liability-driven investment strategies aren’t widely used in the JGB market, where yields have already stabilized now that the initial shock has passed.

But in our view, the most interesting takeaway from the comparison between the Truss and Takaichi episodes stems from an examination of the maturity profiles of the countries’ debt issuance.

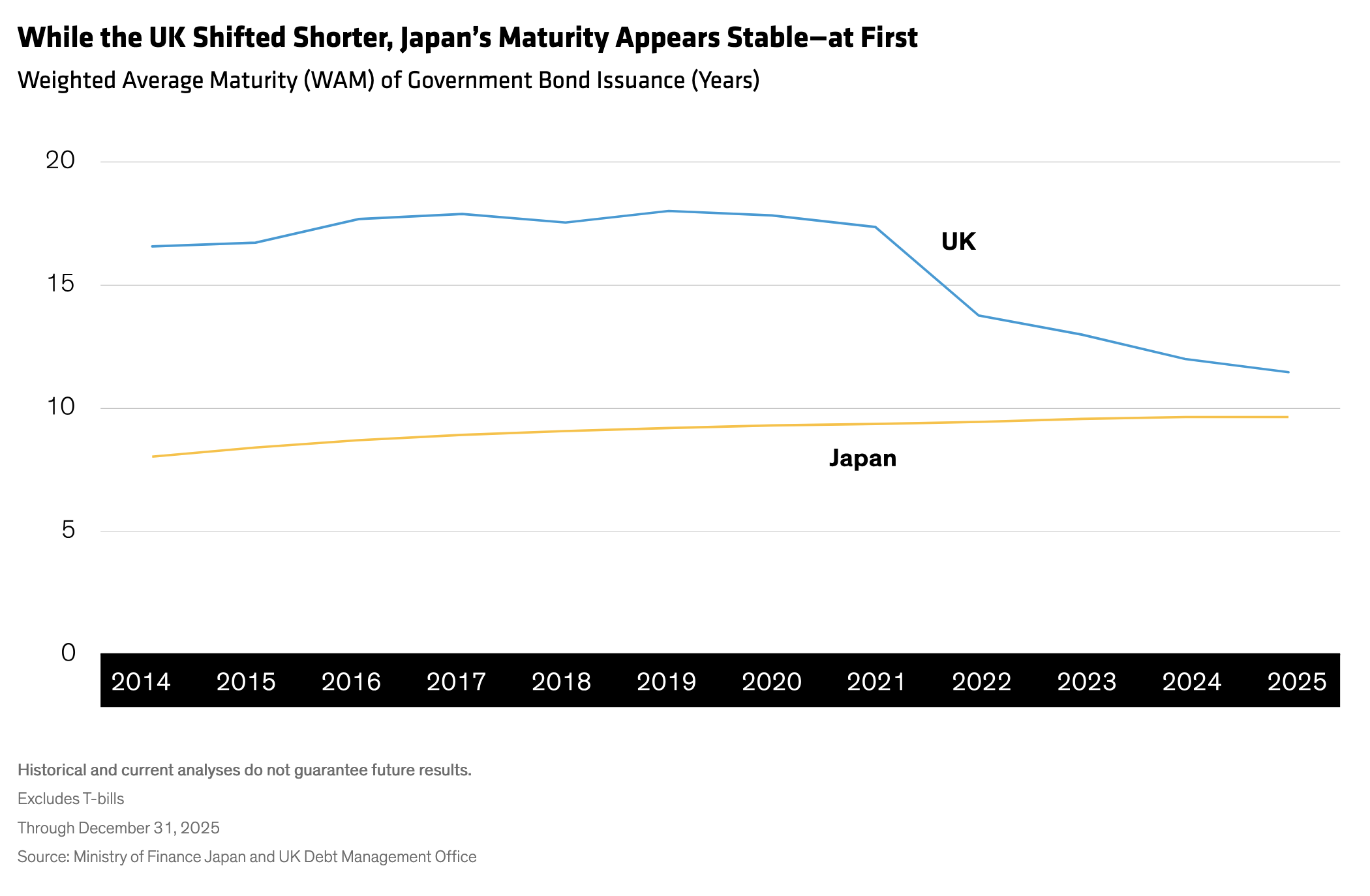

For decades, to minimize refinancing risk, the UK gilt market maintained one of the longest weighted average maturities (WAM) among developed countries. That changed in 2022, when a persistent shortage of demand for long-duration debt forced a rapid shortening of the market’s WAM—a trend that continues today (Display). By contrast, Japan’s WAM appears remarkably stable. But looks can be deceptive.

Uncovering Japan’s Hidden Duration Risk

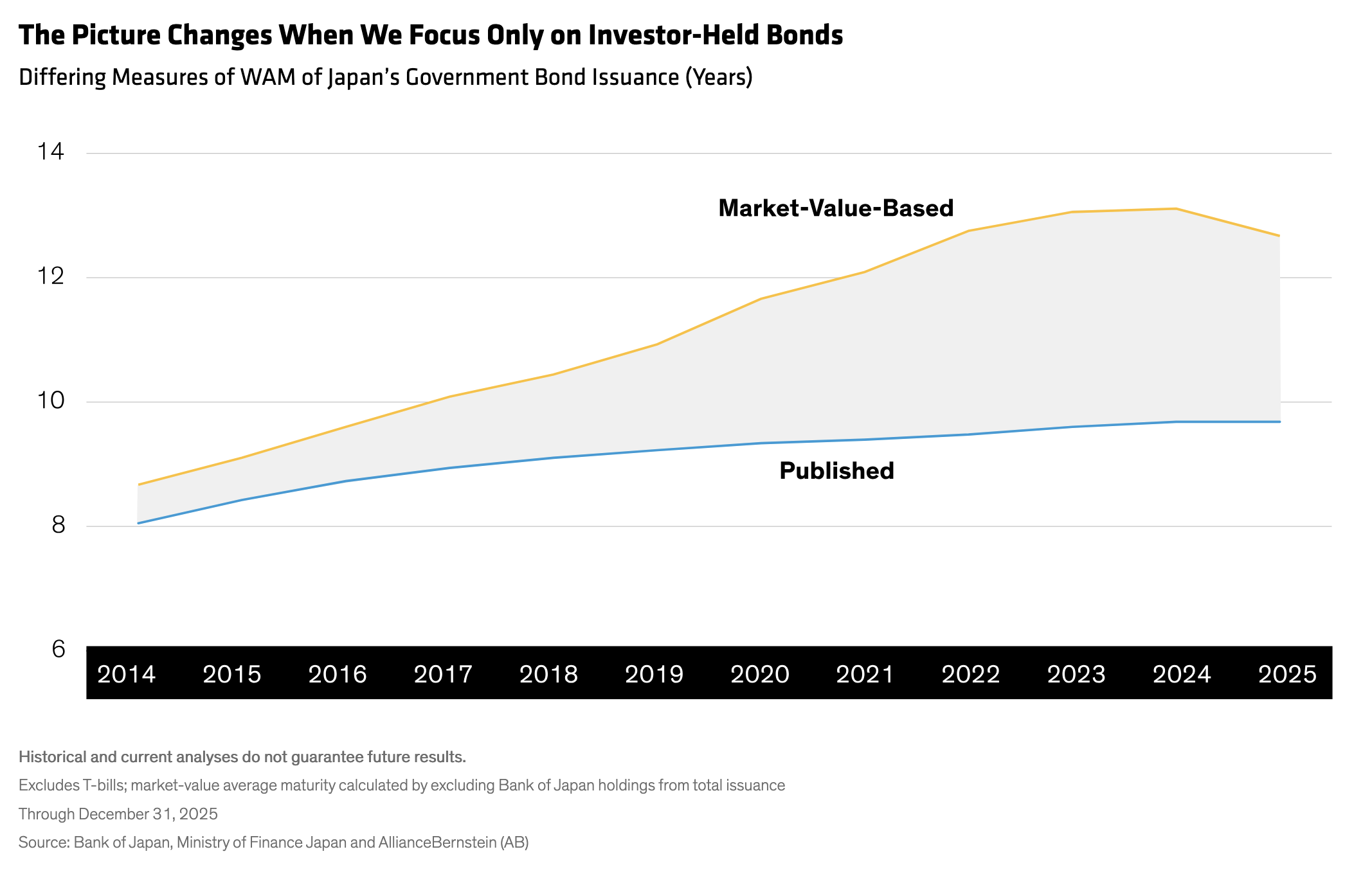

On paper, Japan’s Ministry of Finance (MOF) reports a stable WAM over the last decade. But since the Bank of Japan (BoJ) began large scale bond purchases in 2016, it has absorbed roughly half of JGB supply. Those purchases have been concentrated in bonds up to 10 years, leaving private investors holding a disproportionately long dated portfolio.

When we exclude BoJ holdings and recalculate the WAM, the effective maturity of JGBs held by the market is roughly three years longer than the official number (Display). In other words, headline WAM figures for Japan materially understate the actual duration risk borne by investors. (The Bank of England’s balance sheet is small enough that it doesn’t particularly distort the gilt market’s duration profile.)

That gap between published and market-value WAM explains why Japan’s recent yield-curve steepening was so painful: duration risk was bigger than many investors realized.

Lessons for Investors

Japan’s authorities have already begun to address this gap. Since 2024, Japan’s effective WAM has trended lower as the MOF nudges issuance toward shorter maturities and the BoJ tapers its bond purchases. Progress is slow, due to the BoJ’s outsized balance sheet, but the trend points to Japan’s flexibility in managing its maturity profile.

Looking ahead, we see scope for the MOF to continue to shorten the market’s maturity profile in the coming years through incremental issuance adjustments and for the BoJ to allow Japan’s yield curve to flatten and to ease investor stress.

For investors, the takeaway is simple: look beyond the surface. Headline maturity metrics can be misleading when a central bank holds a large share of the market. Closely tracking Japan’s issuance plans, the pace of BoJ tapering and the effective maturity of bonds in private hands can help anticipate shifts in yield curve behavior—before they surface broadly in markets.

*****

About the Authors

Yusuke Hashimoto is a Vice President and a Portfolio Manager on the Japan Fixed Income team and is a member of the Global Fixed Income and Asia Pacific Fixed Income portfolio-management teams. Prior to joining AB in 2019, he spent 12 years at UBS in several trading roles, most recently as director of Macro Rates Trading. Hashimoto holds a BEc and a MEc, both from the University of Tokyo. Location: Tokyo

Copyright © AllianceBernstein