by Eugenio J. Alemán, Chief Economist, Raymond James

Chief Economist Eugenio J. Alemán discusses current economic conditions.

Back in May of 2024, we wrote a weekly commentary called: “We Can’t Import Cheap Homes; But We Could Import Cheap EV Cars.” In that weekly we argued that since the U.S. auto industry, does not want to build small cars because it is not competitive, then we should open the lower-end EV automåobile industry to imports from China. The weekly was in response to former President Biden’s tariff on Chinese EV imports of 100%. The measure also included a 50% tariff on solar cells, and a 25% tariff on electric vehicle batteries, critical minerals, steel, aluminum, etc.

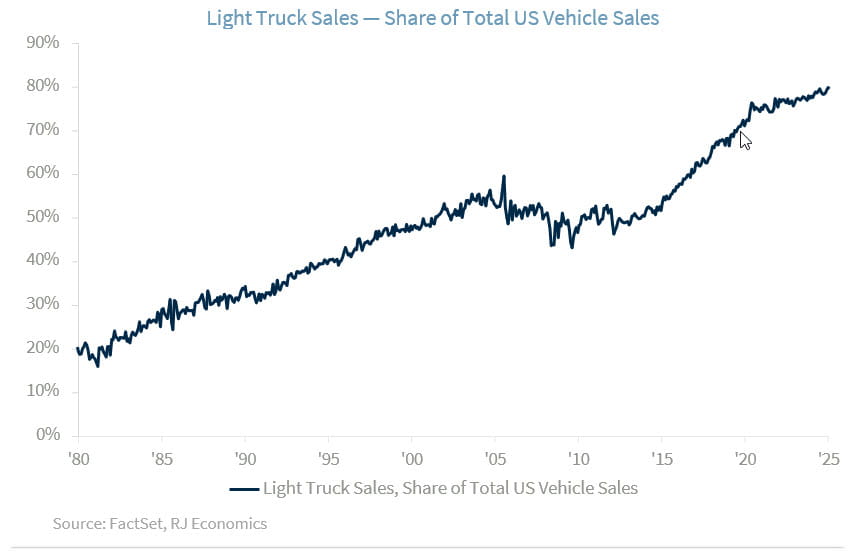

Our argument was based on the fact that our automobile industry was not competitive in small cars (sedans) and had pivoted to the production of large, and very expensive, ‘light trucks.’ Many of these light trucks are gas-guzzling vehicles that are probably only driven in U.S. markets but are not very competitive in other continents. This means that it is very difficult to export them to other countries. More recently, in our February 7, 2025, weekly, which we titled “Fiscal Revenues from Tariffs? We Have Been There Before!,” we talked about a tariff provision we have had since the 1960’s ‘Chicken War,’ which has been called the ‘Chicken Tax,’ a 25% tariff on imported light trucks.

Although there are other reasons for our automobile industry’s tilt towards the production of ‘light trucks,’ we will argue in this weekly that one of the biggest reasons for the tilt (see graph on the previous page) has been as a consequence of the Chicken Tax, that is, the imposition of the 25% tax on the importation of light trucks.1 We argue that the U.S. automobile industry lost its desire to compete in the small passenger car market and concentrated on the production of those automobile segments where the US government provided protection to sustain higher profits over the long run. And, of course, these higher profits were possible due to the shield provided by the Chicken Tax.2

Once again, as we have said in the past, tariffs may be a good policy instrument to fix temporary issues in a specific market but keeping the protection for a long period of time acts against the industry’s competitiveness and sustainability and typically fosters even more protection. That is, tariffs reduce competition and increase the costs of entry into an industry, making that industry less competitive.

Again, there may be good arguments to protect an industry temporarily from unfair competition. In our case, it may be a good idea to protect the new EV industry from competition until our automobile industry becomes more competitive. However, protecting our automobile industry from EV competition when the industry is not interested in producing low-cost EVs for mass consumption because they rather produce for the high-end EV market while also taking advantage of the Chicken Tax, is not a good reason for imposing tariffs on cheap EV automobiles. In this case, tariffs should be imposed if there is an understanding between the government and the automobile sector that the tariff is temporary and conditional on re-engaging in the low-end EV sedan market until they can compete in the global economy.

Footnotes:

1: Other probable reasons include regulatory reasons, like the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA) and the Clean Air Act (CAA) which, together have set lower fuel economy and emission standards than those imposed on passenger cars.

2: See “The Big Three’s Shameful Secret,” by Daniel J. Ikenson, CATO Institute, July 6, 2003. https://www.cato.org/commentary/big-threes-shameful-secret

Copyright © Raymond James