by John H. Fogarty, CFA, Chris Kotowicz, CFA, Adam Yee, AllianceBernstein

Tax cuts alone can’t save a weak business, but high-quality companies can put a tax-break windfall to good use for investors.

The prospect of corporate tax cuts put a brief charge into the US financial markets following the November election of Donald Trump as US president. This short-lived “Trump trade” saw the Dow Jones Industrial Average notch its biggest one-day gain in two years, while the S&P 500 and tech-heavy NASDAQ also climbed to record highs. The bump at least in part reflected investors’ expectations for corporate tax cuts under a new administration that would conceivably boost corporate earnings. But tax cuts don’t affect companies equally, and we believe investors should spend more time focusing on business models than tax regimes.

We’ve been here before. After President-elect Trump’s first victory in 2016, stocks rallied on hopes for corporate tax cuts. Eventually, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017 lopped the top corporate income tax rate from 35% to 21%. This sweeping tax overhaul also repealed the corporate alternative minimum tax, accelerated business deductions and changed how foreign-sourced corporate income is taxed.

Lower taxes help support the competitiveness of US companies on the global stage. But tax cuts don’t make better businesses, and no struggling firm magically became a better buy under the TCJA. On the contrary, corporate tax cuts tend to benefit already-thriving businesses, while undercutting more vulnerable firms. This is especially true in the current environment.

To understand why, we first need to examine how companies react to tax cuts.

Pricing Power Matters in Competitive Markets

Companies can pass along the profit-margin pickup from lower tax rates by reducing prices. But in any market, the return on invested capital (ROIC) within most industries tends to be at or slightly above the cost of capital. This is indicative of a competitive environment where the least-efficient producer tends to set the price of a product. It also works to the advantage of high-quality firms that generate attractive margins at prices that barely sustain weaker competitors. Because these companies enjoy strong pricing power, they can retain a tax windfall for reinvestment rather than pass it on to customers—a strategy we generally favor for growth-oriented companies.

But unlike their weaker peers, strong firms also have other options—especially now. After an extended period of inflation, businesses are currently engaged in some of the most intense price competition seen in decades—a far cry from 2017, when pricing pressure wasn’t nearly as heated. As a result, only the strongest companies can cut prices without doing lasting damage to their bottom line. And some high-quality companies are doing just that—deliberately giving back price to injure weaker competitors. For example, some of the stronger trucking firms are able to make money at rates that would put smaller competitors out of business, while well-positioned big-box retailers are using their scale to invest in meaningful strategic initiatives and take share from smaller players like dollar stores.

The Strong Will Get Stronger with More Tax Cuts

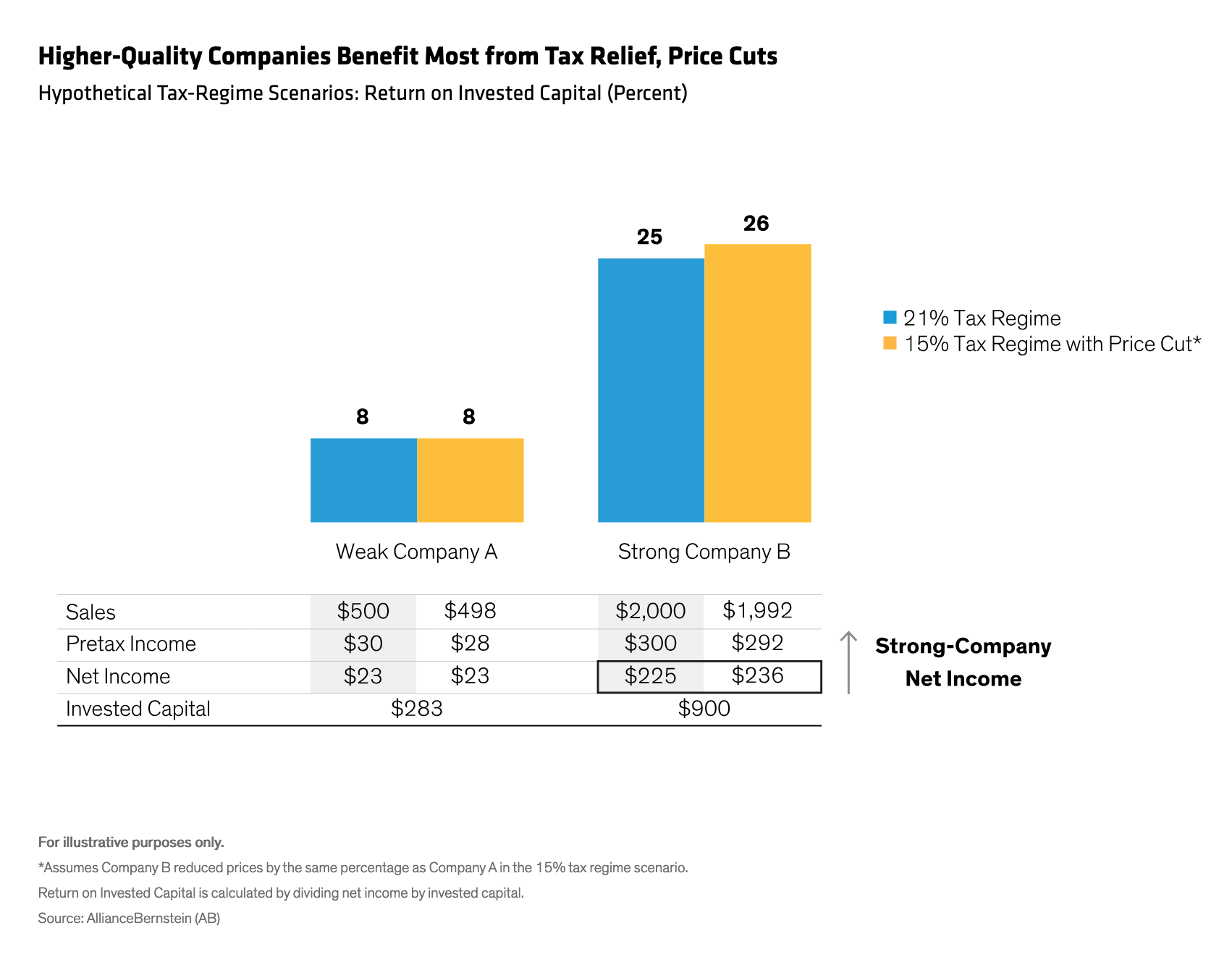

Granted, the strongest companies will only concede as much pricing as the market requires. But at minimum, high-quality firms should be able to match the price cuts of peers and bolster their net income and ROIC if corporate federal tax rates are pared from 21% to 15% (Display), as the president-elect has pledged.

The larger the ROIC gap between the strongest and weakest competitors in an industry, the greater the relative benefit of a tax cut to the strongest players. This allows the strong to get stronger, forcing weaker competitors to the sidelines and increasing industry concentration.

Regardless of what they do with tax cuts, the strongest companies are well-positioned, and we’d expect the after-tax returns of high-quality, cost-efficient companies to surpass those of low-quality, inefficient firms under the new administration.

Investors Should Focus on Quality

What does this mean for investors? If US companies do see lower tax rates under a unified government, we expect at least part of the increased cash flow to be funneled toward investors in the form of stock buybacks and increased dividends. This can be a double-edged sword. Buybacks can goose a company’s earnings per share, but they may also prevent firms from funding otherwise sound ideas in the name of short-term profits.

Longer-term, we believe investors should keep a close eye on competitive positioning, and harness active management to select high-quality companies. After all, it makes little sense to apply a high multiple to what could be a short-lived market boost accruing from lower tax rates. Over extended periods, the stocks of high-quality companies with sustainable business models and strong competitive advantages tend to outperform—even after the sugar high of lower taxes has worn off.

About the Authors

John H. Fogarty is a Senior Vice President and Co-Chief Investment Officer for US Growth Equities. He rejoined the firm in 2006 as a fundamental research analyst covering consumer-discretionary stocks in the US, having previously spent nearly three years as a hedge fund manager at Dialectic Capital Management and Vardon Partners. Fogarty began his career at AB in 1988, performing quantitative research, and joined the US Large Cap Growth team as a generalist and quantitative analyst in 1995. He became a portfolio manager in 1997. Fogarty holds a BA in history from Columbia University and is a CFA charterholder. Location: New York

Chris Kotowicz joined the firm in 2007 and is a Portfolio Manager and Senior Research Analyst for US Relative Value. He is also a Senior Research Analyst for the US Growth Equities team. As a Senior Research Analyst, Kotowicz is responsible for lead coverage of the industrials, energy and materials sectors. He was previously a sell-side analyst at A.G. Edwards, where he followed the electrical equipment and multi-industry group for four years. Prior to that, Kotowicz worked in the industrial sector, mostly in a technical sales and business development capacity, for Nooter/Eriksen and Nooter Fabricators, each a subsidiary of CIC Group. He holds a BS in civil engineering from the University of Missouri, Columbia, and an MBA (with honors) from the Olin Business School at Washington University. He is a CFA charterholder. Location: Chicago

Adam Yee joined the firm in 2004 and is a Senior Vice President and Senior Quantitative Analyst for the US Growth Equities portfolios. He previously served as a senior associate portfolio manager within the Global Portfolio Management Group, where he covered growth equity products. Yee holds a BA in economics from Trinity College and an MBA in finance from Fordham University's Graduate School of Business (now the Gabelli School of Business). Location: New York

Copyright © AllianceBernstein