by Marc Seidner, CIOm Non-traditional Strategies, & Pramol Dhawan, Portfolio Manager, PIMCO

The term “bond vigilantes” refers to investors who discipline excessive government spending by demanding higher sovereign debt yields. Since the 1980s, when strategist Ed Yardeni coined the term, episodes of fiscal excess regularly give rise to questions about when these vigilantes might turn up.

Predicting sudden market responses to long-term trends is difficult. There is no organized group of vigilantes poised to act at a specific debt threshold; shifts in investor behavior typically occur at the margin and over time. Therefore, if you’re seeking clues about the potential for bond vigilantism, you might start by asking the largest fixed income investors – who theoretically hold the most market sway – what they’re doing.

At PIMCO, we are already making incremental adjustments in response to rising U.S. deficits. Specifically, we’re less inclined to lend to the U.S. government at the long end of the yield curve, favoring opportunities elsewhere. Here’s our latest thinking.

Concerns and opportunities

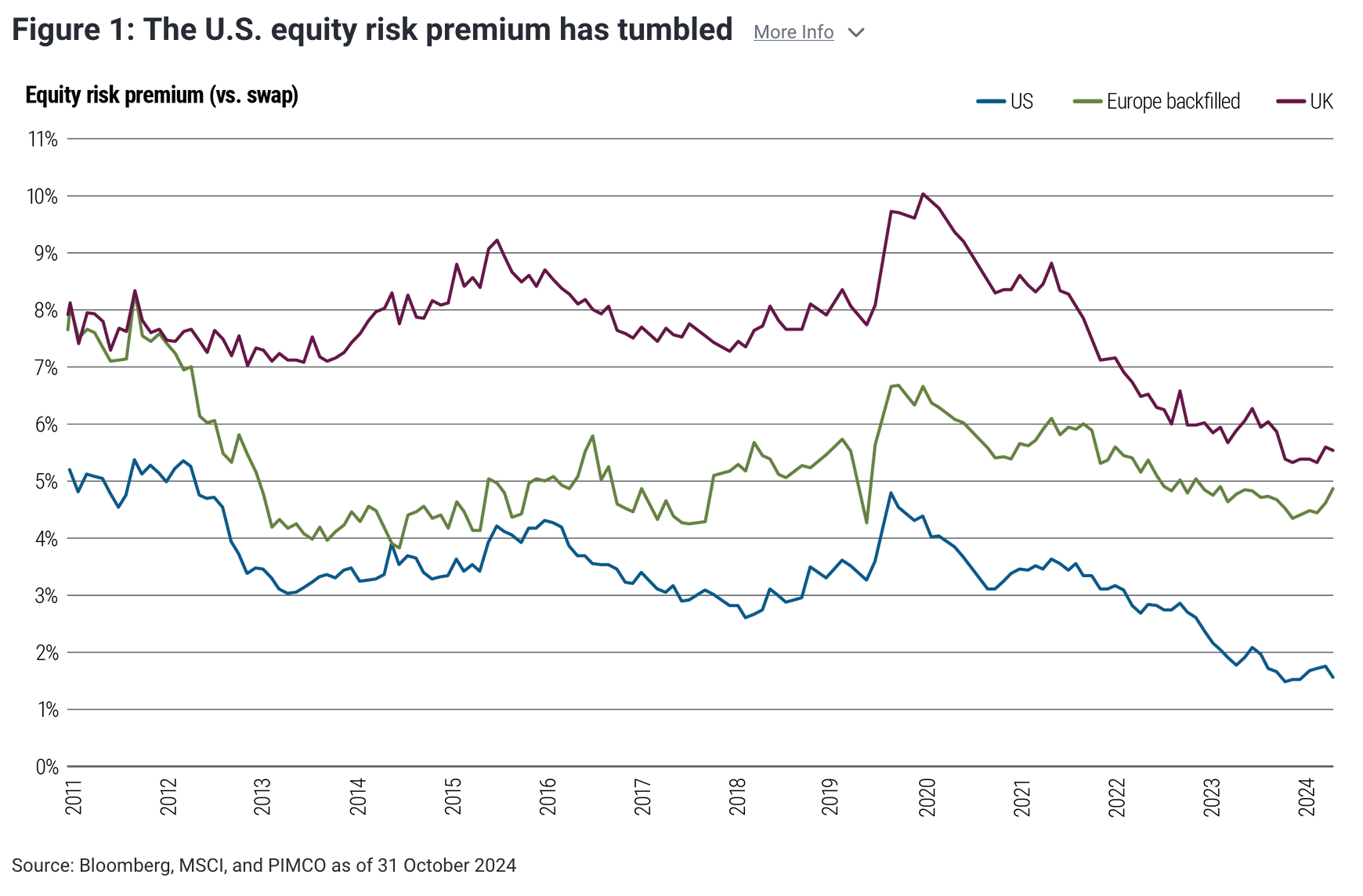

Fiscal stimulus helped to fuel a post-pandemic U.S. economic recovery while propelling stock markets to record heights. Although equities may rise further, valuations appear more stretched, with the U.S. equity risk premium – a gauge of investor compensation for owning stocks over a risk-free rate – near record low levels (see Figure 1).

That stimulus also fueled a surge in U.S. indebtedness. Debt and deficit levels are high even in today’s strong economy and will likely keep growing. The Federal Reserve in November cited U.S. debt sustainability as the biggest concern among survey participants in its semiannual financial stability report.

Given the potential investment implications of this rising U.S. debt trajectory, here are three approaches we favor:

-

- Targeting short- and intermediate-dated bonds. We expect the U.S. Treasury yield curve to steepen, fueled in part by deteriorating deficit dynamics (for more, see our July Economic and Market Commentary, “Developed Market Public Debt: Risks and Realities”). That implies a relative rise in yields for longer-term bonds, which are influenced by the prospects for inflation, economic growth, and government policies – including the potential for increased Treasury issuance to fund deficits. Longer-term bonds typically have a higher duration, or price sensitivity to interest rate changes.We have been reducing allocations to longer-dated bonds, which we find relatively less attractive. Over time, and at scale, that’s the kind of investor behavior that can fulfill the bond vigilante role of disciplining governments by demanding more compensation. We prefer short and intermediate maturities, where investors can find attractive yields without taking greater interest rate risk.

Although we regularly adjust allocations along the yield curve to express evolving views on duration and relative value, rising sovereign debt has become a greater factor in these decisions.

- Targeting short- and intermediate-dated bonds. We expect the U.S. Treasury yield curve to steepen, fueled in part by deteriorating deficit dynamics (for more, see our July Economic and Market Commentary, “Developed Market Public Debt: Risks and Realities”). That implies a relative rise in yields for longer-term bonds, which are influenced by the prospects for inflation, economic growth, and government policies – including the potential for increased Treasury issuance to fund deficits. Longer-term bonds typically have a higher duration, or price sensitivity to interest rate changes.We have been reducing allocations to longer-dated bonds, which we find relatively less attractive. Over time, and at scale, that’s the kind of investor behavior that can fulfill the bond vigilante role of disciplining governments by demanding more compensation. We prefer short and intermediate maturities, where investors can find attractive yields without taking greater interest rate risk.

- Diversifying globally. We’re lending in global markets to diversify our interest rate exposures. The U.K. and Australia exemplify high quality sovereign issuers with stronger fiscal positions than the U.S. They face greater economic risks as well, which can benefit bond investors. We also like high quality areas of emerging markets that offer yield advantages over developed markets.Non-U.S. bonds can also help hedge equity exposure in portfolios. If you contrast fiscal policies, we believe it makes sense to be structurally short the U.S. public sector versus the private sector, while the opposite generally holds true in Europe, where growth momentum has stalled and fiscal responses remain constrained.

In essence, the U.S. boasts a stronger income statement while the European Union largely has a stronger balance sheet. It’s a trade-off between growth and durability. The U.S. can grow but is in uncharted deficit territory. The EU is struggling to grow but has been able to navigate turbulence, such as Brexit and the Greek debt crisis, although we remain cautious on select European countries.

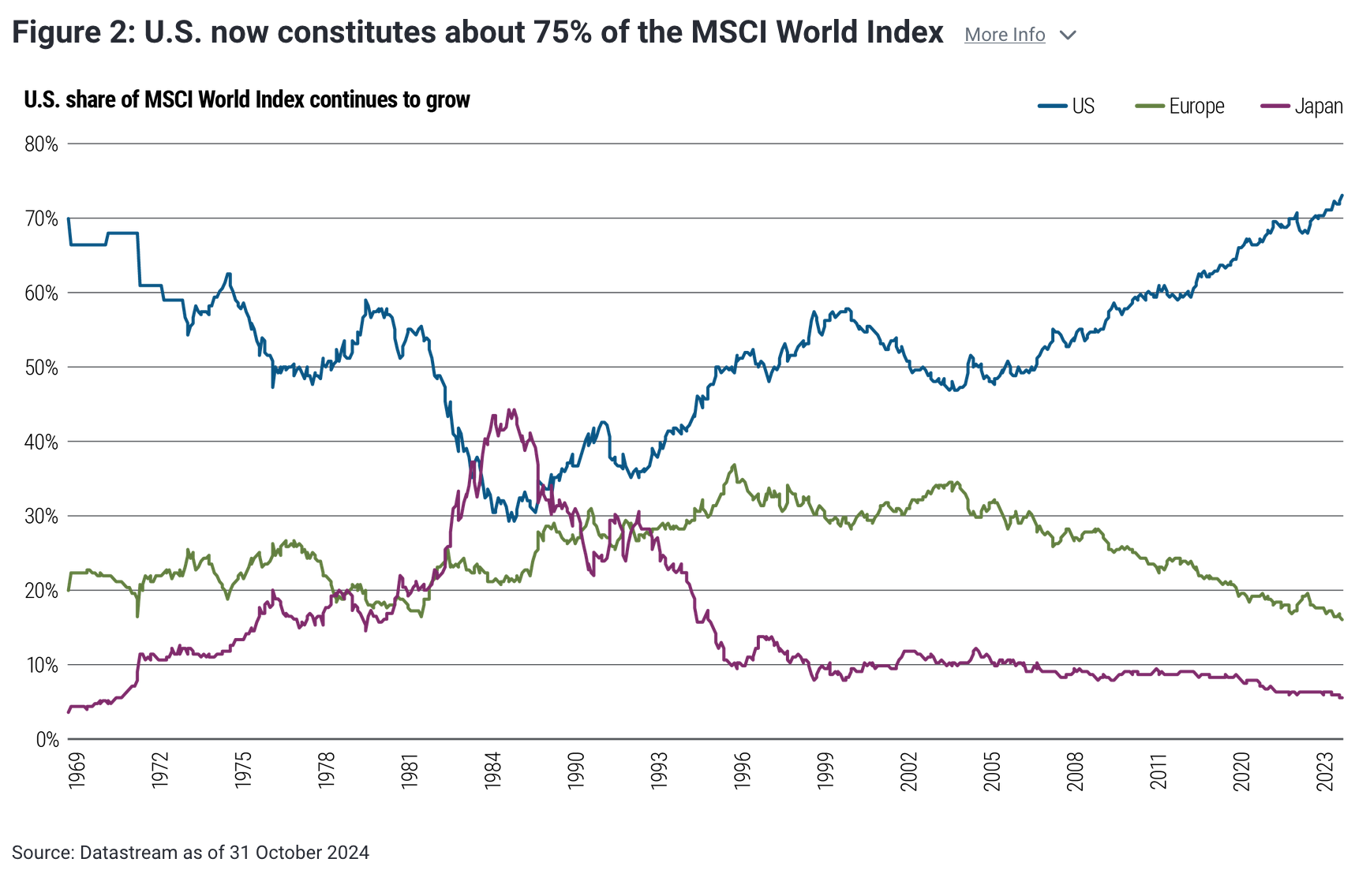

The U.S. might ultimately prove resilient, but uncertainty builds as debt keeps rising. The U.S. social contract – large deficit-fueled growth – has spurred a productivity and technology boom to the benefit of U.S. companies and stock investors (see Figure 2). We therefore believe it makes sense to take equity exposure in the U.S. and prefer debt exposure in Europe.

- Targeting higher credit quality. For companies as well as governments, rising debt levels can affect creditworthiness. We favor lending to higher-quality companies in public and private markets alike. Credit spreads are near historic lows in some sectors, with diminished reward for moving down in credit quality to boost yield. In public credit markets, high quality bonds offer attractive yields and appear well positioned across various economic scenarios. In private markets, we favor asset-based finance over lower-rated areas of corporate direct lending.

Vigilance before vigilantism

By some measures, investors have already been demanding higher yields to lend in the bond market. In November, the yield to worst on the benchmark Bloomberg US Aggregate Index climbed above the effective federal funds rate for the first time in more than a year. That also illustrates how bond yields overall have become more attractive than cash rates as the Fed has begun to cut its policy rate.

At the same time, we have become more hesitant to lend longer term given U.S. debt sustainability questions and potential inflation catalysts, such as tariffs and the effects of immigration restrictions on the labor force. The U.S. remains in a unique position because the dollar is the global reserve currency and Treasuries are the global reserve asset. But at some point, if you borrow too much, lenders may question your ability to pay it all back. It doesn’t take a vigilante to point that out.

Copyright © PIMCO