by Jeffrey Kleintop, Chief Global Market Strategist, Charles Schwab & Company

Potential for another trade war fueled by a rise in global protectionist policies has investors revisiting the potential impact on stocks, inflation, and economic growth.

A trade war is an economic conflict marked by rising tariffs and other protectionist trade barriers. After experiencing trade war tariffs in 2018-19 (Trade War 1.0), investors are revisiting the topic, and the potential impact on stocks, inflation, and growth fueled by the rise in "my country first" policies in this year's elections across the globe. In summary, here are the key impacts of a trade war for investors:

- Do tariffs hurt stock market performance? On average, our analysis shows little impact on stocks after tariff announcements during Trade War 1.0, and the stocks of more domestically focused companies did not outperform those with a high proportion of international sales.

- Do tariffs lift inflation? Although tariffs can potentially lift inflation to the extent the costs of the additional tax are passed on to consumers, the U.S. consumer price index (CPI) remained relatively stable at around 2% during Trade War 1.0 in 2018-19.

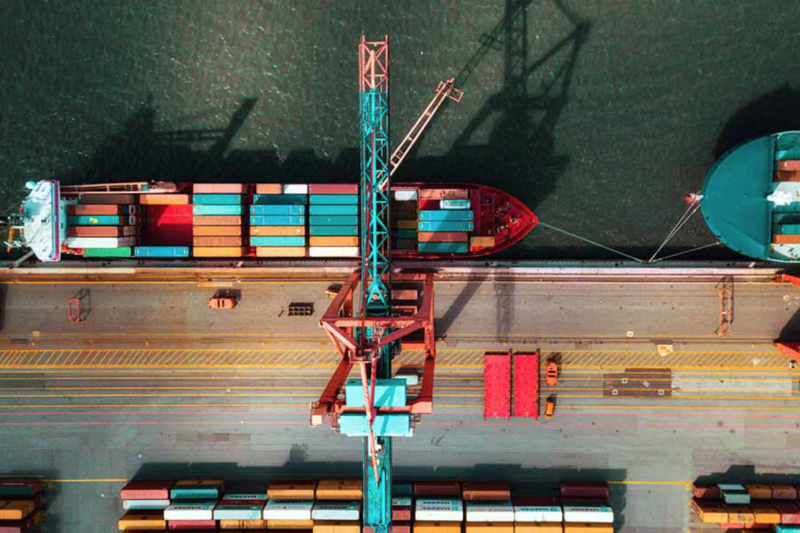

- Do tariffs hurt growth by reducing trade? We did not see a decline in global trade due to increased tariffs during Trade War 1.0 and global trade volumes are currently near an all-time high. Although rerouting of goods through intermediaries to avoid tariff expenses may be coming more common, tariffs have other effects which can act as a drag on growth.

The potential for a Trade War 2.0 re-escalation and global expansion of trade restrictions does pose a risk to expected central bank rate cuts, which are sensitive to inflation moves, and to the nascent global manufacturing recovery lifting global growth this year (especially to exporters that may be subject to retaliatory tariffs). Yet, the overall impact for investors is likely to be more volatility but less downside risk in the markets than what headlines might suggest.

Stocks

Stock markets, represented by the MSCI All Country World Index (ACWI), have had a neutral reaction to past trade war escalations, as listed in the table below. It appears that broad global growth and low inflation in 2018-19 calmed fears over an escalating U.S.–China trade war. But the manufacturing downturn, drop in trade volumes and elevated inflation over the past two years may have prompted the market to take more cautious note of trade war escalations with the worst weekly declines experienced in 2022 and 2023. There could be more to come in the lead up to the U.S. elections in November.

Market reaction to trade tensions

Source: Charles Schwab, various news sources, Bloomberg performance data as of 7/26/2024.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

The results in the above table for the overall MSCI All Country World Index were similar for the stock markets of the U.S. and China, measured by the S&P 500 and the MSCI China Index. For example, the largest of the stock market declines was in response to the U.S. announcement of an increase tariffs from 10% to 25% on $200 billion of Chinese made goods on May 10, 2019. On that day, the MSCI All Country World Index fell 1.9%, the S&P 500 Index fell 2.4% and the MSCI China Index fell 1.2%.

Of course, a Trade War 2.0 may be broader than Trade War 1.0, which primarily focused on economic conflict between the U.S. and China. The potential for an expansion can be seen in the European Union (EU) tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles. Europe is the main destination for Chinese electric vehicle exports, valued at $11.5 billion in 2023, up from just $1.6 billion in 2020, according to Rhodium Group. On June 12 of this year, following the EU parliamentary elections, the EU proposed hefty tariff increases on imports of electric vehicles made in China of 17.4% to 37.6% added on top of the existing 10% duty. These tariff hikes were implemented in early July. Although China has yet to announce any retaliatory tariffs, European auto industry executives are cautious. German auto manufacturers made a third of their sales last year in China according to company reports. The MSCI All Country World Index rose on the 12th of June and gave back some of those gains on the 13th, while five days after the announcement the index was higher.

Other post-election tariffs the EU announced included higher tariffs on imports of titanium dioxide from China on July 10, raising the tariff up to 39.7%. This chemical is commonly used in a wide range of consumer products, including pharmaceuticals, sunscreen, cosmetics, and toothpaste. Stocks around the world, including those in Europe and China, rose on the 10th.

The stock market reactions to the Trade War 1.0 and to large tariff increases in Europe suggest that the impact of a potential global Trade War 2.0 on stocks may be muted.

It is also noteworthy that stocks of companies in the S&P 500 that were domestically focused did not fare better than those with a high percentage of international sales during Trade War 1.0. In fact, a Bloomberg constructed index of S&P 500 companies with lower international sales underperformed an index of companies with higher international sales by over 9% during 2018-19. This suggests implementing a strategy to avoid stocks more exposed to rising trade tensions may not be beneficial.

Inflation

Tariffs may result in some increase in cost being passed on to end consumers, but for each product it can differ. To illustrate, we'll focus on U.S. tariffs that U.S. companies importing goods or parts from China would pay to the U.S. government at the time of customs clearance. Companies may either pass through the higher cost on to consumers or absorb the cost and lower their profit. Alternatively, Chinese exporters could reduce their selling prices to stay competitive and/or move manufacturing to other countries for future export to the U.S. to avoid the tariff.

Significantly, during the Trade War 1.0 the backdrop of weak global demand for manufactured goods and slowing trade helped keep inflation from rising. U.S. inflation, as measured by the CPI, didn't spike until 2021-22, when pandemic supply shortages combined with a demand boost from record-breaking fiscal stimulus.

Inflation remained muted during Trade War 1.0

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg data as of 7/23/2024.

Another reason inflation remained subdued during 2018-19 was that the tariffs were mainly focused just on China. U.S. importers were often able to get around tariffs by importing Chinese made goods through other nations. Overall tariff levels remained historically low.

Average tariff rates remain historically low following Trade War 1.0

Source: Charles Schwab, Macrobond, United Nations Trade & Development as of 7/26/2024.

Growth

The world has shown no evidence of a long-term decline in international trade since Trade War 1.0 began, as you can see in the chart below. In fact, global trade volume hit a new all-time high in 2021 after rebounding from the pandemic and remains near its peak.

Global trade volume near all-time high

Source: Charles Schwab, CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis, Bloomberg data as of 7/23/2024.

While there appears to be a protectionist movement on the rise around the world, the actual impact on international trade and sources of revenue for business is not straightforward. Business decisions like manufacturing relocation, such as Chinese businesses establishing operations in other countries before exporting to the U.S, or running multiple supply chains to diversify risk, localize production closer to customers and avoid the risks associated with long transportation routes can dull the impact of protectionist measures. There is also evidence that businesses in China seem to be increasingly routing trade to other Asian nations, such as Vietnam, Cambodia, and Thailand, on the way to the U.S. perhaps to avoid U.S. tariffs on Chinese goods. In the chart below, we can see the increase in Chinese exports to these countries and the offsetting U.S. imports from these Asian countries both picking up after the 2018-19 Trade War 1.0. Lastly, the impact of tariffs varies from product to product due to nuances in supply and demand of individual goods, the ability to substitute for goods not subject to tariffs, and the tariff level assigned to a particular import.

China exports rerouted to U.S. via Southeast Asia

Source: Charles Schwab, U.S. Commerce Department, China Customs Statistics Information Center, data as of 7/20/2024.

In contrast to the increasing headlines on rising trade frictions, there have been more trade facilitating actions according to the World Trade Organization, or WTO, (such as easing paperwork rules, approving new foreign businesses for expedited processing, lowering tariffs, and eliminating quotas) than trade restrictions including tariffs since the Trade War 1.0 (2018-19). The WTO data shows a steady rise in trade facilitating measures over the past 10 years relative to the rise and fall of trade restrictions in 2018-19, suggesting a more welcoming international trade environment than what might be assumed from headlines.

Trade War 1.0 spike in trade restrictions versus steady rise in trade facilitating measures

Source: WTO Secretariat, as of 7/8/2024.

Note: these figures are estimates and represent the trade coverage of the measures (i.e. annual imports of the products concerned from economies affected by the measures) introduced during each reporting period, and not the cumulative impact of the trade measures.

There are other factors to consider when assessing the impact of tariffs on growth beyond the level of trade. To the extent manufacturing can be shifted to the U.S., there is potential for increased U.S. employment in industries protected by tariffs. However, other industries dependent upon imports of intermediate goods subject to tariffs, or whose exports are hit by countervailing tariffs can end up losing jobs and profits. Job growth may also suffer if economic growth is lower due to the impact of higher inflation.

China may continue to enact countervailing tariffs on U.S. exports, which can hurt Chinese demand for U.S. goods. In April of 2018 Chinese countervailing tariffs on U.S. agricultural exports boosted the tariff on soybeans from 3% to 25%, impacting over half of U.S. exports of the commodity. This retaliation prompted the U.S. government to provide billions in aid to U.S. farmers whose soybean crops destined for China had their orders cancelled. There are many U.S. businesses across industries, not just agriculture, with a high percentage of their sales coming from China. For example, Qualcomm gets two-thirds of its revenue from China, General Motors gets nearly half, while Tesla gets about a quarter, as does Sketchers.

Trade war takeaways

Tariffs and trade trends are more complicated than headlines tend to imply. While trade restrictions appear to again be on the rise, there's uncertainty over the extent that campaign talking points end up being enacted as policies. Factors like changes in demand and countervailing tariff reactions are difficult to forecast. While a potential Trade War 2.0 may extend globally and involve higher tariffs than Trade War 1.0, suggesting higher potential volatility, the muted reaction in stocks, inflation, and growth in 2018-19 is comforting. This fact combined with the outperformance by those stocks more exposed to trade during that period suggest investors may want to stick to their long-term allocation targets and avoid making trade war trades.

Michelle Gibley, CFA®, Director of International Research, and Heather O'Leary, Senior Global Investment Research Analyst, contributed to this report.

Copyright © Charles Schwab & Company