by Lance Roberts, RIA

In bullish years, markets often have corrections. Yet, after a lengthy bullish run, it always surprises me how quickly investors and the media panic with the slightest hint of a market pullback.

During bullish years, corrections happen more often than you think. However, when corrections occur, it is not uncommon to see concerns about a “bear market” rise. However, historically speaking, the stock market increases about 73% of the time. The other 27% of the time, market corrections reverse the excesses of the previous advance. The table below shows the dispersion of returns over time. Critically, note that drawdowns of greater than 10% only occur 13% of the time.

However, 10% or less market corrections are more common and occur in every bullish year, as shown.

As investors, we must focus on probabilities versus possibilities. As noted, 38% of the time, the market is cranking out 20% or returns versus just a 6% chance of a greater than 20% correction. While the possibility of a 20% is not zero, the probability of a market advance outweigh those more rare events.

More importantly, a correction of more than 20% rarely happens in the middle of a bullish year. That is because “momentum” and “bullish psychology” drive markets higher. Secondly, drawdowns greater than 20% are almost always associated with an exogenous event like the 2008 banking crisis or the “Dot.com” crash.

Therefore, as we look at the current market, we must evaluate the possibilities versus probabilities of the current market correction devolving into something more egregious.

So Far, Just A Healthy Correction

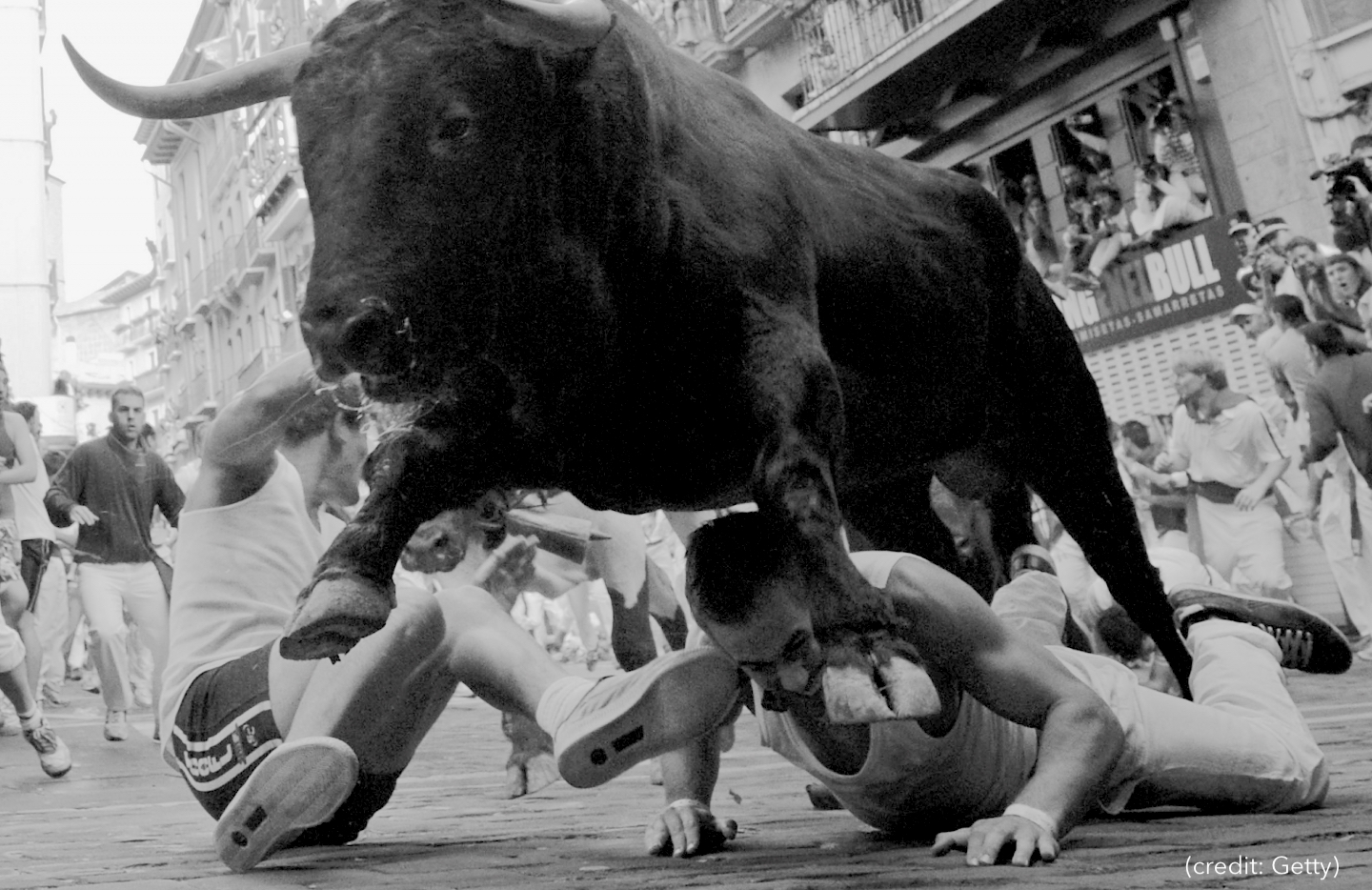

In a market driven by bullish momentum, it is challenging to abruptly change its direction without the influence of an outside force. Think about it this way via the Physics Classroom:

“The sports announcer says, ‘Going into the all-star break, the Chicago White Sox have the momentum.’ The headlines declare ‘Chicago Bulls Gaining Momentum.’ The coach pumps up his team at half-time, saying ‘You have the momentum; the critical need is that you use that momentum and bury them in this third quarter.”

Momentum is a commonly used term in sports. A team that has the momentum is on the move and is going to take some effort to stop. A team that has a lot of momentum is really on the move and is going to be hard to stop. Momentum is a physics term; it refers to the quantity of motion that an object has. A sports team that is on the move has the momentum. If an object is in motion (on the move) then it has momentum.

Momentum can be defined as “mass in motion.” All objects have mass; so if an object is moving, then it has momentum – it has its mass in motion. The amount of momentum that an object has is dependent upon two variables: how much stuff is moving and how fast the stuff is moving. Momentum depends upon the variables mass and velocity. In terms of an equation, the momentum of an object is equal to the mass of the object times the velocity of the object.“

The markets currently have both “mass,” a large contingent of equity buyers, and the “velocity” of increasing asset prices. Notably, we are nearing one of investors’ longest streaks of “risk-on” behavior. (h/t @sentimentrader)

Considering a speeding train with both mass and velocity, what would it take to stop that momentum abruptly? According to the laws of physics, applying a force “against” its motion for a given period is necessary. The more momentum an object has, the harder it is to stop. Thus, it would require a more significant amount of force, a more extended period, or both to bring such an object to a halt. As the force acts upon the object for a given amount of time, the object’s velocity is changed, and hence, the object’s momentum changes.

In the case of our speeding train, applying its brakes will slow it down gradually over a long distance, or a “derailer” can stop it immediately with devastating consequences.

The stock market has many of the same characteristics. In bullish years, market momentum can push asset prices for an extended period. However, there are points where “brakes” are applied, slowing that momentum. As shown, periods of “risk on” behavior can last for extended periods before a gradual reversal occurs.

However, you will note that in 2020, the market’s bullish momentum was “derailed” by the pandemic-related economic shutdown. That 35% decline was an unexpected, exogenous event that surprised investors. We saw the same during the “financial crisis” in 2008. However, outside of those two exogenous events, investor positioning and sentiment reversals, which lead to a loss of momentum, involved price corrections of 20% or less. As noted above, most of those corrections were 5-10%.

There is no evidence currently of an exogenous event that would “derail” the financial markets. Credit spreads, as shown, remain significantly suppressed, and economic data, while weakening, is not recessionary.

So far, the current correction, which has recently worried investors and the media, remains an expected and rather ordinary correction within a bullish year. As we noted in our previous Bull Bear Report:

“Such suggests that, as we saw in late May and June, the market will either consolidate or correct back to the 20-DMA. If the bulls can hold that level again, as they have, the market could continue to push higher. Such is possible given the current exuberance surrounding the Fed cutting rates. However, if the 20-DMA fails, as in early April, the 50-DMA becomes the next logical support, with the 100-DMA close behind. Such would encompass another 3-5% correction.“

That correction process could encompass as much as 10%, as we saw in the summer of 2023.

However, like last summer, when investors should have been buying, they didn’t. This is because declines tend to lead investors to make one of the most significant investing mistakes.

Anchoring – The Biggest Mistake We Make

The thing that pushes individuals into making investing mistakes is almost always psychological. Yes, the pullback in the indices over the last two weeks certainly woke up overly complacent investors, both retail and professional alike. However, the pullback was unsurprising and a possibility we have discussed over the last few weeks.

Market corrections often trigger the “Anchoring effect” or the “relativity trap.” Anchoring is the tendency to compare our current situation within the scope of our limited experiences. Most investors become anchored to the value of their portfolio from one day, week, or month to the next. When that value is rising, we remember that value vividly. If there is a gain in that value, it is a positive event, and therefore, we assume that the next period will have a similar result.

When an inevitable correction comes, we measure the current value as the “high water mark.” The temporary loss of market momentum triggers investors into another psychological behavior of “loss avoidance,” where they exit the financial markets to avoid further losses.

These emotionally driven decisions often lead to inferior outcomes, and “anchoring” is one of our most significant mistakes.

To minimize that risk, “anchor” on the portfolio’s value two or three years ago. In any given market year, stocks will correct anywhere from 5% to 20%. However, focusing on the difference between principal value and gains will reduce the impulse to make drastic decisions that lead to poor investing outcomes.

Make Better Bad Choices

My nutrition coach had a great saying about dieting; “make better bad choices.”

We are all going to make bad choices from time to time. The goal is to try to make bad choices that don’t have an outsized effect on our investing. For example, when it comes to dieting, if you eat a burger, order it without cheese and mayonnaise.

The current market correction is likely just that—an ordinary pullback that is normal within every bullish year. Could it devolve into something larger? Absolutely, but the credit and stock markets “technicals” will likely provide sufficient warning.

However, if you feel you must “do something,” make small changes to avoid the risks of “bad decisions.”

- Do more of what is working and less of what isn’t.

- Remember that the “Trend Is My Friend.”

- Be either bullish or bearish, but not “hoggish.” (Hogs get slaughtered)

- Remember, it is “Okay” to pay taxes.

- Maximize profits by staging buys, working orders, and getting the best price.

- Look to buy damaged opportunities, not damaged investments.

- Diversify to control risk.

- Control risk by always having pre-determined sell levels and stop-losses.

- Do your homework.

- Not allow panic to influence buy/sell decisions.

- Remember that “cash” is for winners.

- Expect, but do not fear corrections.

- Expect to be wrong, and will correct errors quickly.

- Check “hope” at the door.

- Be flexible.

- Have the patience to allow your discipline and strategy to work.

- Turn off the television, put down the newspaper, and focus on your analysis.

Importantly, keep your market perspectives and behavioral traits in check. We aim to ensure that reliable data and psychological emotions influence our decisions.

Most importantly, if you don’t have an investment strategy and discipline you are stringently following, that is an ideal place to begin.

Copyright © RIA