by Ryan Boyle, Senior Economist, Northern Trust

Metals from Mexico may have a much further point of origin.

Growing up near a river taught me how water will always find its own level. During floods, stacked sandbags were rarely impervious, and submersible pumps were no match for a river's flow. Houses on our street were at risk not from direct inundation, but from the river filling storm drains and backing into home sewer lines.

The global economy has been reckoning with a flood of exports out of China, and hastily erected barriers are struggling to contain the flow. The United States has led the push against China's export power, levying an array of tariffs and export controls meant to reduce the competitiveness of Chinese output. These polices are showing some evidence of progress, such as the share of U.S. imports from China now falling to second place behind a resurgent Mexico. But some of that shift is likely a redirected flow, not the end of the flood.

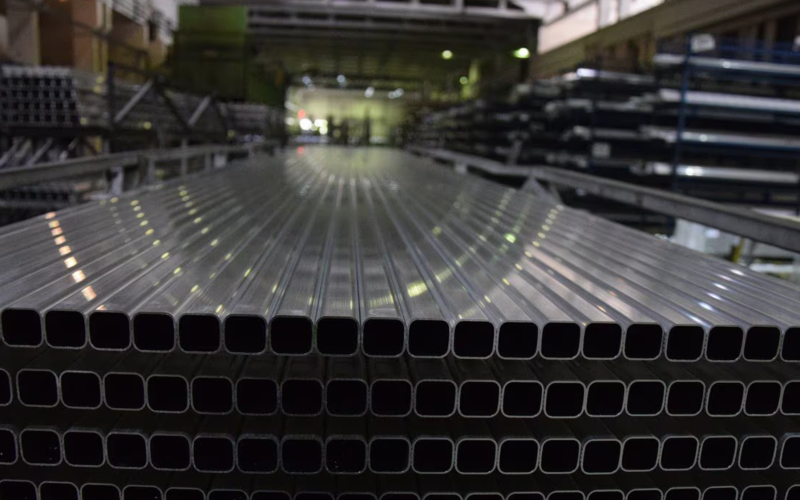

The world has become awash in exported metals from China. The U.S. has tried to reduce its use of these metals by levying tariffs of 25% on imported steel and 10% on imported aluminum since 2018. Only a handful of nations have negotiated exceptions, including America's neighbors through the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) free trade deal.

As China's obstacles at the U.S. border accumulated, Chinese metals started flowing south to Mexico, and then finding their way north with the advantage of the USMCA. This allowed China to keep its foundries running, despite much lower domestic demand for new construction.

The backdoor is not as simple as shipping to an alternate port. Trans-shipments, or goods passing directly through Mexico to the U.S., are identified and tariffed. Instead, raw materials like metals are traveling from China to Mexico, to be processed and finished for export to the U.S.

In many cases, the processing may be done by Chinese entities. Foreign direct investment from China into Mexico reached a record high in 2022 and has remained elevated. Whole industrial parks are being built and populated by Chinese investors. Chinese inputs are manipulated enough to place a Made in Mexico label on the finished product.

This process of white-labeling is drawing increased scrutiny. The scheme was not addressed in the terms of USMCA, nor its predecessor NAFTA. The white-labeled metal products are produced in Mexican factories using Mexican labor; the claim that they are made in Mexico is not fraudulent. The automotive industry has long had a similar tension between vehicles' material origins and their point of final assembly.

Last week, the Biden administration imposed a new set of national security tariffs to curb white labeling. Any steel entering the U.S. from Mexico must have been melted and poured in North America, or it will face 25% tariffs. The statement was made jointly by the Mexican administration, which promised to require importers to provide more information about metal products' origins.

Like the recent round of tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles, the measure is intended to stop a foreseeable outcome before it gains momentum. U.S. officials estimate 13% of steel and 6% of aluminum imports from Mexico are processed outside the continent and will now face the tariffs.

Mexican metals are just one market. Chinese steel can flow to other nations, distorting domestic metal production elsewhere. And more broadly, the U.S. is the world's largest consumer, and China is the world's leading exporter. Container shipments from China to Mexico are on the rise, poised to distort many other product categories. Piecemeal barriers to trade will not overcome such sizable forces of demand and supply.

Flood-prone communities understand that lasting, effective remediation is a slow and expensive process. Civil engineering to reduce flooding is costly and time consuming; relocating to higher ground is disruptive. Faced with rising flood waters, simple but imperfect measures like sandbags are the only option.

A realignment of global supply chains will also be a cumbersome process, but thoughtful interventions today can help reduce the mess that will need to be cleaned up in the years to come.

Copyright © Northern Trust