by Sonal Desai, Ph.D., Chief Investment Officer, Franklin Templeton Fixed Income

Franklin Templeton Fixed Income CIO Sonal Desai discusses why rising investment and persistently loose US fiscal policy are simultaneously pushing in the direction of higher long-term real interest rates.

Two driving forces are now simultaneously pushing in the direction of higher long-term real interest rates. While investors and commentators often tend to conflate the two, I think it is useful instead to distinguish them clearly. They are rising investment, and persistently large fiscal deficits.

A new trend toward stronger investment has emerged and is likely to endure for the next several years, driven by a number of important priorities: (a) there is a need to make up for past under-investment in infrastructure, including traditional infrastructure as well as digital infrastructure. The American Society of Civil Engineers’ latest report assigns a failing grade to overall US infrastructure (not for the first time)1; (b) rising geopolitical tensions necessitate an increase in defense spending across Western countries; (c) growing interest in the potential of Artificial Intelligence calls for new investment in the necessary hardware (notably semiconductors), software and energy; (d) the green energy transition requires more investment to boost the role of renewables; and (e) manufacturing companies need to continue to invest in new technologies, which includes making supply chains more resilient.

Not all of this will result in rapid gains in productivity. For example, while the green energy transition is a very important goal, a lot of the required investment will not increase productivity growth in the short and medium run. Because it consists of replacing existing capital, it increases current economic growth via higher expenditures, but it does not raise productivity—much like rebuilding existing structures after they’ve been destroyed by a hurricane. The economist Jean Pisani-Ferry, in a recent report for the French government, has estimated that in fact investment in the green transition will likely reduce productivity growth by a quarter percentage point per year for the next several years. (The report also warns that the green transition increases inflation risks over the next decade)2.

However, the bulk of investment should over time result in faster productivity growth (the acceleration in US productivity during 2023 already gives hope, even if the weak first quarter of this year counsels caution). Faster productivity growth should in turn drive faster real economic growth, reversing one of the key arguments of the Secular Stagnation theory3, and implying a higher equilibrium interest rate in the long run.

Moreover, for a given level of savings, stronger investment also eliminates or reduces the “savings glut,” again pointing to higher real interest rates.

The government has and will carry out some of this, and investment is therefore often mentioned in the same breath as wider fiscal deficits. But the two need not go hand in hand. Governments could offset stronger public investment with a reduction in less productive public spending (or with higher taxes). Moreover, a significant portion of governments’ investment often turns out to be ineffective at raising productivity—the private sector has consistently been a much better allocator of capital.

The United States has experienced a persistent loosening of fiscal policy that goes well beyond the country’s public investment efforts. Therefore, quite separately from lifting investment, persistent large fiscal deficits now play their own important role in shaping the outlook for interest rates. The US government has been running a massively loose fiscal policy for a very long time now: The US fiscal deficit has averaged close to 8% of gross domestic product (GDP) for the last six years. It averaged just under 6% of GDP during 2022-2023 even as economic growth boomed, and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects the deficit to average 5.5% of GDP for the next five years and then to rise further into the future. As a consequence of persistent large deficits, the debt stock has risen sharply. A decade ago, publicly held federal debt was about 70%; now it is close to 100% of GDP and will keep rising rapidly if deficits remain as large as the CBO forecasts.

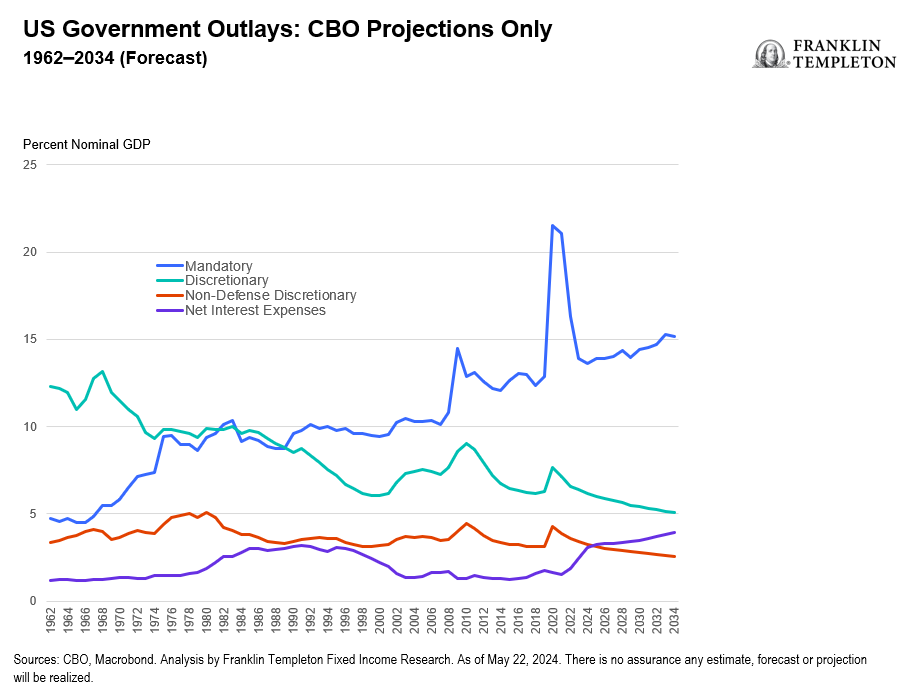

The need to fund large fiscal deficits year after year means a lot of pressure on bond supply. For a given level of demand, this tends to push bond prices down and interest rates up. Moreover, a large fiscal deficit, growing debt and high interest rates create a vicious spiral that makes it harder and harder to reduce the deficit. Currently, non-defense discretionary expenditures account for less than one-sixth of the US budget (15% of total expenditures). Interest expenditures meanwhile keep rising—they averaged just 1.5 % of GDP in the last 10 years. The CBO projects that they will average 3.5 % of GDP for the next 10 years, more than double, and will grow larger than non-defense discretionary spending by 2025. This would leave very few resources for education, infrastructure investment, transportation, homeland security and the like.

And, the underlying CBO forecasts are probably conservative: They assume that the interest rate on federal debt will remain under 3.5% over the next decade. To put this assumption in perspective, consider that through the 1990s up to the eve of the global financial crisis (GFC)—in other words before the more recent period of ultra-loose monetary policy—the interest rate on US government debt averaged close to 6%. If the average interest rate on debt were to rise even just one percentage point above the CBO assumption (still well below the pre-GFC average), within 10 years interest expenditures would be more than double their current level.

Any way you cut it, bringing the US budget deficit under control will require very serious efforts, which in my view seems implausible in the current political climate. Meanwhile, loose fiscal policy will likely continue to put upward pressure on interest rates.

I have been arguing for some time that equilibrium real interest rates are likely much higher than the markets and the Federal Reserve (Fed) still seem to assume—with the neutral fed funds rate above 4% rather than at the Fed’s current forecast of about 2.5%, and 10-year US Treasury yields correspondingly higher. The confluence of loose fiscal policy and a rising investment trend can only strengthen my conviction in this higher interest rates outlook.

*****

WHAT ARE THE RISKS?

All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal.

Fixed income securities involve interest rate, credit, inflation and reinvestment risks, and possible loss of principal. As interest rates rise, the value of fixed income securities falls. Low-rated, high-yield bonds are subject to greater price volatility, illiquidity and possibility of default.

IMPORTANT LEGAL INFORMATION

This material is intended to be of general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice. This material may not be reproduced, distributed or published without prior written permission from Franklin Templeton.

The views expressed are those of the investment manager and the comments, opinions and analyses are rendered as at publication date and may change without notice. The underlying assumptions and these views are subject to change based on market and other conditions and may differ from other portfolio managers or the firm as a whole. The information provided in this material is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region or market. There is no assurance that any prediction, projection or forecast on the economy, stock market, bond market or the economic trends of the markets will be realized. The value of investments and the income from them can go down as well as up and you may not get back the full amount that you invested. Past performance is not necessarily indicative nor a guarantee of future performance. All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal.

Any research and analysis contained in this material has been procured by Franklin Templeton for its own purposes and may be acted upon in that connection and, as such, is provided to you incidentally. Data from third party sources may have been used in the preparation of this material and Franklin Templeton (“FT”) has not independently verified, validated or audited such data. Although information has been obtained from sources that Franklin Templeton believes to be reliable, no guarantee can be given as to its accuracy and such information may be incomplete or condensed and may be subject to change at any time without notice. The mention of any individual securities should neither constitute nor be construed as a recommendation to purchase, hold or sell any securities, and the information provided regarding such individual securities (if any) is not a sufficient basis upon which to make an investment decision. FT accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss arising from use of this information, and reliance upon the comments, opinions and analyses in the material is at the sole discretion of the user.

Products, services and information may not be available in all jurisdictions and are offered outside the U.S. by other FT affiliates and/or their distributors as local laws and regulation permits. Please consult your own financial professional or Franklin Templeton institutional contact for further information on availability of products and services in your jurisdiction.

Please visit www.franklinresources.com to be directed to your local Franklin Templeton website.

Copyright © Franklin Templeton Fixed Income

___________________________

1. Source: “2021 Report Card for America’s Infrastructure.” American Society of Civil Engineers, 2021.

2. Source: Pisani-Ferry, Jean and Mahfouz, Selma. “The economic implications of climate action.” Republique Francaise. November 2023. There is no assurance that any estimate, forecast or projection will be realized.

3. Secular Stagnation theory suggests that an economy can experience persistent low GDP growth, low interest rates, and high long-term unemployment due to a deficiency in aggregate demand.