by Richard Bernstein Advisors

The current speculative environment seems to increasingly resemble the Technology Bubble of 1999/2000. Leadership is narrow, valuation dispersions are massive, relative strength and momentum are the primary drivers of performance, and investors are shunning diversification to take impulsive near-record portfolio risk.

All bubbles eventually burst, and the bursting of the Tech Bubble led to the so-called lost decade in equities during which the S&P 500® provided negative returns for a decade. When today’s speculative burst ends, the equity markets’ extreme concentration again makes it likely an extended period of subpar performance for equities will occur.

Today’s consensus remains focused on the Magnificent 7¹ stocks, but no sound financial theory counsels that seven stocks constitute a well-diversified portfolio as a core for building wealth. The possibility of another lost decade in equities and the broad range of investment opportunities outside the Magnificent 7 leads us to position our portfolios with significant diversification (See Chart 1).

1999/2000 bubble formation

The combination of the excitement of new internet technology changing the economy and considerable central bank liquidity that couldn’t be fully absorbed by the real economy helped fuel the 1999/2000 Tech Bubble.

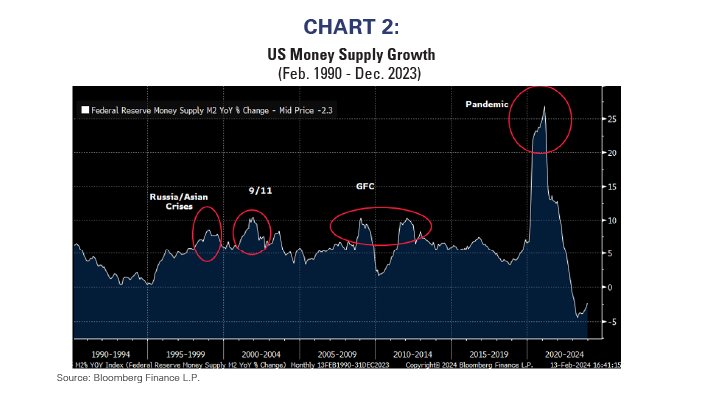

Despite consistently strong US GDP growth between 3.5% and 6.5%, the Fed eased in 1997/98 because of several emerging market financial crises (mainly the Russian Ruble and Asian crises and the collapse of Long-Term Capital Management). US M2 money supply growth rose to nearly 8%, but the economy was already healthy and couldn’t absorb the excess liquidity. The excess liquidity acted as a stimulant for the Tech Bubble.

While it’s true that US money growth was higher following 9/11, the global financial crisis, and the COVID pandemic, 1998’s liquidity infusion wasn’t associated with a falloff in economic activity, so excess liquidity flowed to financial assets rather than to rebuilding the economy (see Chart 2).

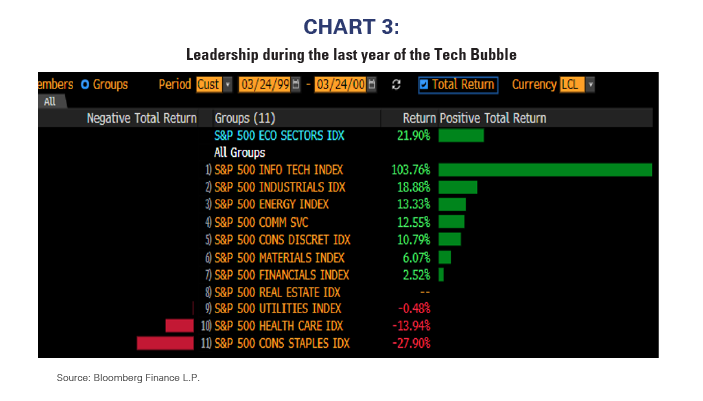

There was very narrow leadership during the Tech Bubble as only a few sectors were considered part of the “new economy” (stocks related to the potential growth of the internet). Traditional businesses, termed “old economy” stocks, significantly underperformed. Chart 3 highlights that only one sector, Technology, outperformed the overall market during the last year of the bubble.

The lost decade in equities

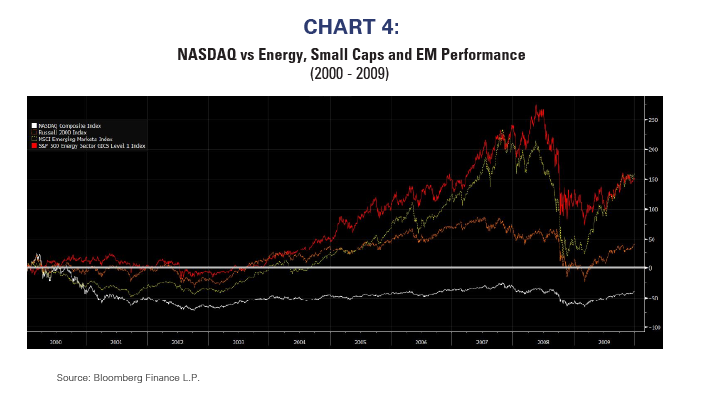

Once the Tech Bubble deflated, the equity market began an extended period of underperformance which came to be known as “the lost decade in equities.” From December 31, 1999 to December 31, 2009, the S&P 500® returned -1%/year, whereas NASDAQ returned -5%/year [or -6%/year for the NASDAQ 100]. In fact, if one had bought NASDAQ at the peak of the Tech Bubble in March 2000, it would’ve taken nearly 14 years to simply break even!

However, certain segments within the global equity markets performed extremely well during the lost decade. Chart 4 shows NASDAQ’s extended underperformance (white line) versus the significant outperformance of the energy sector, small caps, and emerging markets.

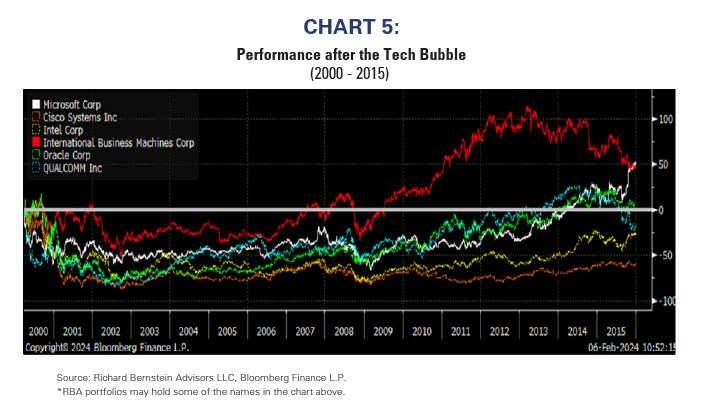

There seems a common misperception that the current speculative period of narrow outperformance is vastly different from that during the Tech Bubble because the Magnificent 7 companies are “real companies” and not the worthless IPOs issued during the Tech Bubble. Few seem to realize the Tech Bubble was indeed led by real companies.

Chart 5 recaps what happened to the 6 largest Technology companies (as of December 1999) after the Tech Bubble burst. These were real companies with strong balance sheets and cash flow. The quickest stock to post positive returns still took roughly 7 years to recover. The longest recovery among these real companies was more than 20 years, i.e., much longer than the period shown in the chart. (Note: RBA may own the companies mentioned in various portfolios.)

Today’s bubble

The bubble today isn’t being inflated by stories of the internet, but by a similar story about the exciting future of artificial intelligence (AI). The combination the AI hype and immense pandemic-related liquidity that has not been fully absorbed into the real economy has inflated equity valuations and created highly speculative and narrow leadership.

US M2 growth peaked at 27% which is the highest in modern US history. That huge money growth, like the money growth that fueled the Tech Bubble, could not be fully absorbed into the real economy, and has fueled another financial bubble.

The extreme amounts of excess liquidity have also fueled a bubble in cryptocurrencies. Chart 6 shows the close relationship between financial conditions and Bitcoin. As there is no tangible legitimate economic use for Bitcoin, this relationship demonstrates well that excess liquidity and easier financial conditions are prime determinants of Bitcoin’s value.

Investors should seriously question the narrow leadership and valuations of the so-called Magnificent 7 stocks. Whereas some of today’s Magnificent 7 do have strong fundamental growth, that growth isn’t uniform within the seven stocks nor is it unique relative to many non-Magnificent 7 companies’ growth prospects. Chart 7 shows there are currently about 140 stocks within the G-7 equity markets (US, Canada, Germany, Japan, France, the UK, and Italy) projected to grow earnings 25% or more over the next year. Most importantly, only 3 of the Magnificent 7 pass the screen and the fastest growing of the Magnificent 7 ranks only 25th.

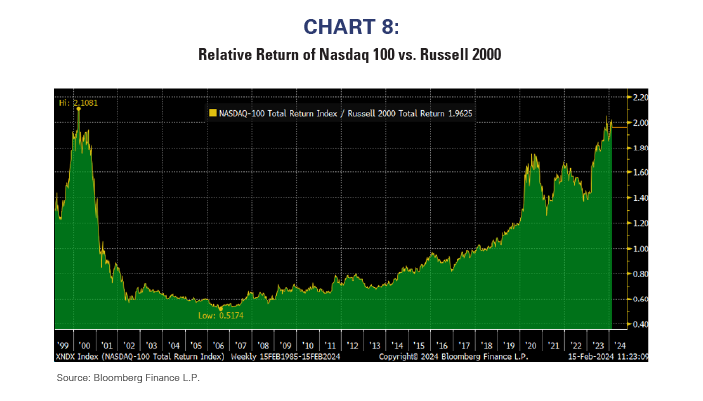

The relative performance between the NASDAQ 100 and the Russell 2000 is as extreme as it was during the Tech Bubble. Chart 8 shows the relative total return between the two indices. History seems to be repeating: new technology hype, significant liquidity, bubble outperformance, investors’ enthusiasm and risk-taking. Will another lost decade in equities be next?

Diversification is the key to avoiding another lost decade

Investors should consider what they are missing with their Magnificent 7 myopia. Shunning diversification has never been prudent, and that’s certainly true during bubble environments. The key to future returns may be simple, basic diversification.

As we emphasized in the first chart, the range of underappreciated investment opportunities seems historically broad and historically attractive. Given the last time similar opportunities arose was after the Tech Bubble, which was 24 years ago, we don’t think we are exaggerating when we describe this as a once-in-a-generation opportunity.

¹Mag 7: Magnificent 7: Alphabet, Nvidia, Tesla, Microsoft, Apple, Amazon, Meta

INDEX DESCRIPTIONS: The following descriptions, while believed to be accurate, are in some cases abbreviated versions of more detailed or comprehensive definitions available from the sponsors or originators of the respective indices. Anyone interested in such further details is free to consult each such sponsor’s or originator’s website. The past performance of an index is not a guarantee of future results. Each index reflects an unmanaged universe of securities without any deduction for advisory fees or other expenses that would reduce actual returns, as well as the reinvestment of all income and dividends. An actual investment in the securities included in the index would require an investor to incur transaction costs, which would lower the performance results. Indices are not actively managed and investors cannot invest directly in the indices. S&P 500®: S&P 500® Index: The S&P 500® Index is an unmanaged, capitalization-weighted index designed to measure the performance of the broad US economy through changes in the aggregate market value of 500 stocks representing all major industries. Sector/Industries: Sector/industry references in this report are in accordance with the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS®) developed by MSCI Barra and S&P Global. Small Caps: Russell 2000. The Russell 2000 Index is an unmanaged, market-capitalization-weighted index designed to measure the performance of the small-cap segment of the US equity universe. The Russell 2000 Index is a subset of the Russell 3000® Index. Nasdaq: The Nasdaq Composite Index: The NASDAQ Composite Index is a broad-based market-capitalization-weighted index of stocks that includes all domestic and international based common type stocks listed on The NASDAQ Stock Market. Nasdaq®-100: The NASDAQ-100 Index is a modified capitalization-weighted index of the 100 largest and most active non-financial domestic and international issues listed on the NASDAQ. No security can have more than a 24% weighting. The index was developed with a base value of 125 as of February 1, 1985. Prior to December 21,1998 the Nasdaq 100 was a cap-weighted index. EM: MSCI Emerging Markets (EM) Index. The MSCI EM Index is a free-float-adjusted, market-capitalization-weighted index designed to measure the equity-market performance of emerging markets.