by Scott DiMaggio, CFA, Co-Head—Fixed Income; Director—Global Fixed Income

Gershon M. Distenfeld, CFA, Co-Head—Fixed Income; Director—Credit

Matthew Sheridan, CFA, Lead Portfolio Manager—Income Strategies, AllianceBernstein

Do high-yield bonds still make sense for income investors at this stage of the credit cycle? We think so.

With the global economy slowing under the weight of central bank rate hikes, many income-seeking investors are shying away from high-yield corporate bonds. We understand. Historically, high yield took a hit when growth slowed. But instead of bracing for a wave of downgrades and defaults, we think income-seeking investors should embrace high yield. Here’s why.

Fundamentals Remain Unusually Strong

At the brink of most slowdowns, corporate fundamentals are typically already weak. And while high-yield issuer fundamentals are beginning to weaken now, they’re starting from an unusually strong position at this late stage of the credit cycle.

Today’s high-yield bond issuers are in much better shape financially than issuers entering past slowdowns, thanks in part to the extended period of uncertainty surrounding the coronavirus pandemic. This uncertainty led companies to manage their balance sheets and liquidity conservatively over the past few years, even as profitability recovered. As a result, leverage and coverage ratios, margins, and free cash flow improved.

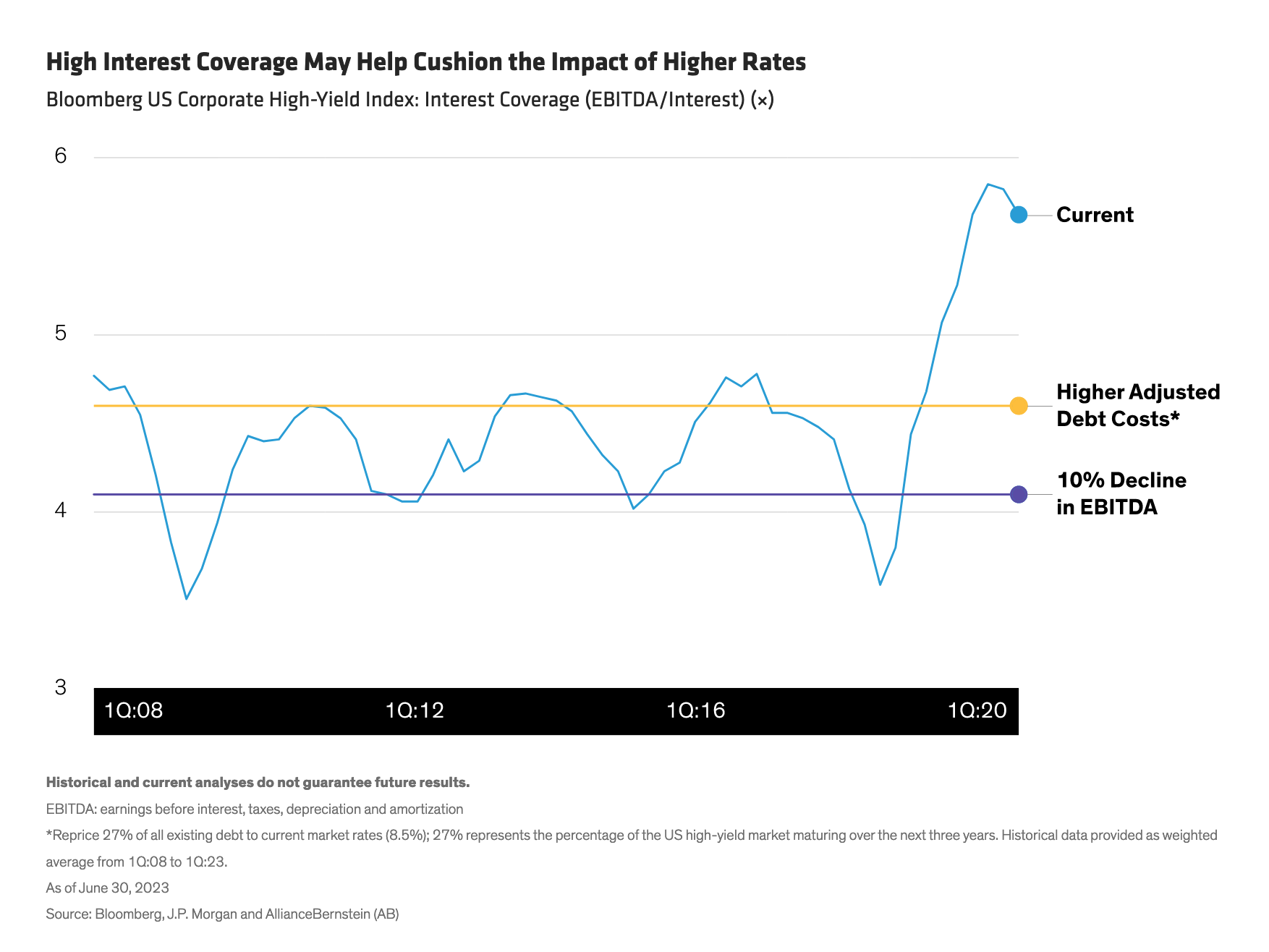

In fact, interest coverage ratios are currently so high that they’re likely to remain above 4× even if issuers refinance at today’s rates or earnings decline sharply (Display). This relative strength in balance sheets means corporate issuers can withstand more pressure as growth and demand slow.

Prudent fiscal management isn’t the only reason the corporate universe is well positioned. The default cycle triggered by the pandemic—with defaults peaking at 6.3% in October 2020—effectively cleaned up the sector. The weakest companies defaulted and are now no longer part of the investable universe. Only the strong survived. That was less than three years ago. Since then, there simply hasn’t been enough time for the survivors to develop unhealthy financial habits.

The pandemic-led wave of defaults and downgrades boosted the average quality of the high-yield market. Even as many of the lowest-rated high-yield bonds defaulted and fell out of indices, many of the lowest-rated investment-grade bonds fell into the high-yield market as fallen angels. Consequently, the quality of today’s high-yield market is unusually high, with BB-rated bonds comprising 49% of the market, versus 43% on average over the past 20 years.

Since the start of the pandemic, companies have also alleviated financial pressure by extending their maturity runways. That means there’s no approaching maturity wall, where a large share of bond issues matures and issuers are compelled to procure new debt at prevailing rates. (Today, the average high-yield coupon is 5.9%—significantly lower than prevailing yields, at 8.5%.) In fact, only 5% of the market will mature by the end of 2024, with most maturities coming between 2027 and 2033. Gradual and extended maturities slow the impact of higher yields on companies.

As a result, we expect a moderate default rate for the next 12 to 18 months—around 4% to 5%. What’s more, the share of the high-yield bond market that is secured—31% as of December 31, 2022—is high by historical measures, which may translate into higher recovery rates in the event of default.

That said, we think investors should favor higher-quality credits, be selective and pay attention to liquidity. CCC-rated credits—particularly those in cyclical industries—are most vulnerable in an economic downturn and represent the lion’s share of defaults. Yield spreads for CCC debt also tend to widen more dramatically than those of higher-quality bonds—about three times as much, in our analysis. Debt rated B and BB may be a better choice in today’s environment.

High-Yield Bonds at Bargain Prices

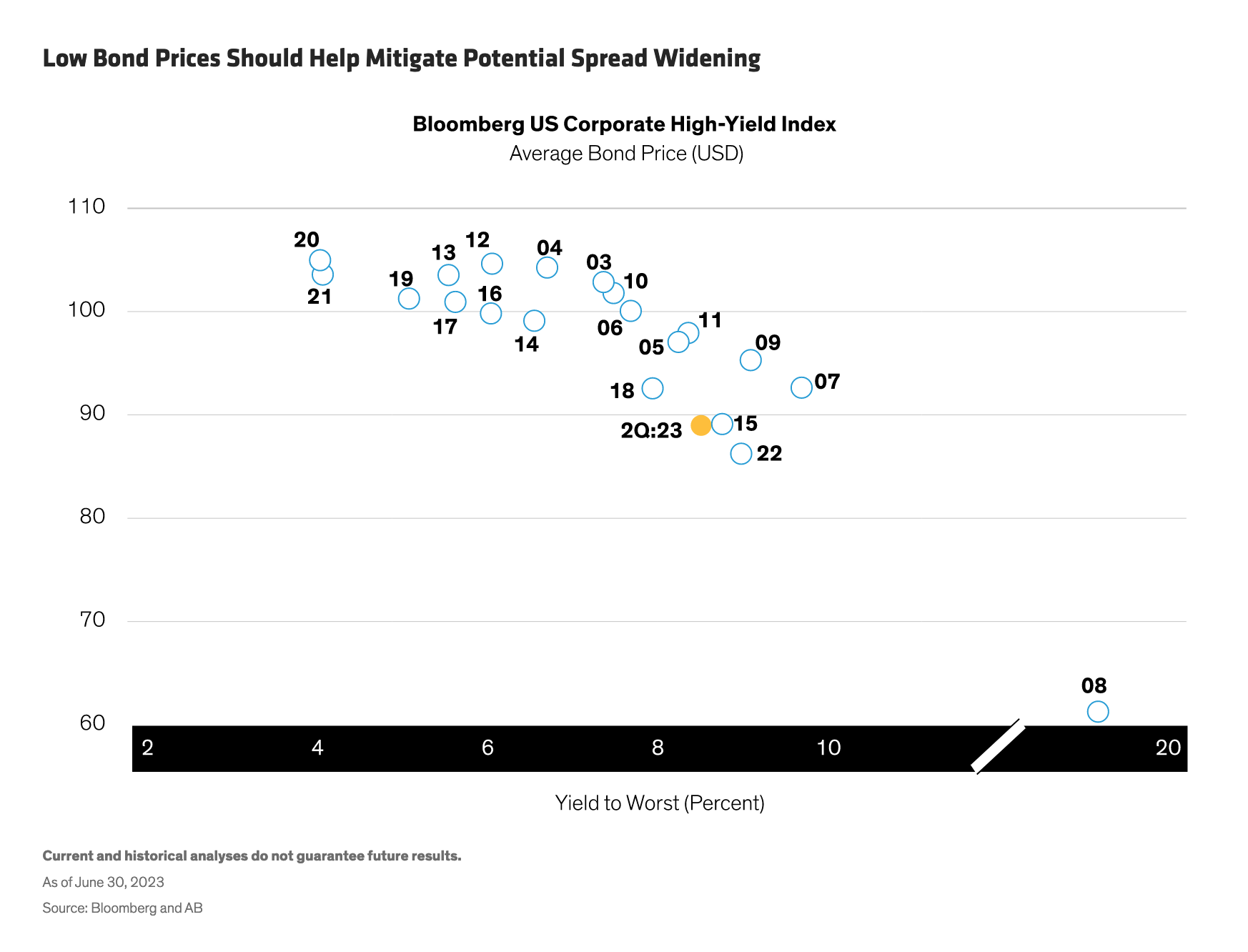

Yields on high-yield corporate bonds are higher today than they’ve been in years, giving income-seeking investors a long-awaited opportunity to fill their tanks. And because yields are so high, bond prices are extremely low, contributing to a compelling convexity profile. When bonds have high positive convexity, their prices rise more than would be expected as interest rates fall, and their prices fall less than would be expected as rates rise.

In fact, at less than $90 today, average bond prices have rarely been lower (Display). It would take an extreme shock to push prices much further down. Because bonds eventually mature at par, prices are much more likely to rise from today’s bargain levels than to fall further. And if bond prices do fall, ample yield levels would cushion the effect.

Consider a range of possible scenarios. If economic growth plateaus over the next 12 months, we’d expect Treasury yields to hold steady and spreads to tighten slightly. But our base-case scenario—and one that’s becoming increasingly the consensus—calls for a soft landing, which would likely result in modestly lower Treasury yields, modestly wider spreads and mid-single-digit returns over the next 12 months. It would take a hard landing and a dramatic widening of spreads to drive high-yield returns into negative territory. That scenario is least likely, in our analysis.

(Notably, even in the event of a hard landing, an allocation to high-yield debt can be a good thing. High-yield drawdowns have historically been less severe than equity-market drawdowns, helping high yield provide downside mitigation in the context of overall allocations.)

Locking in High Yield’s High Yields

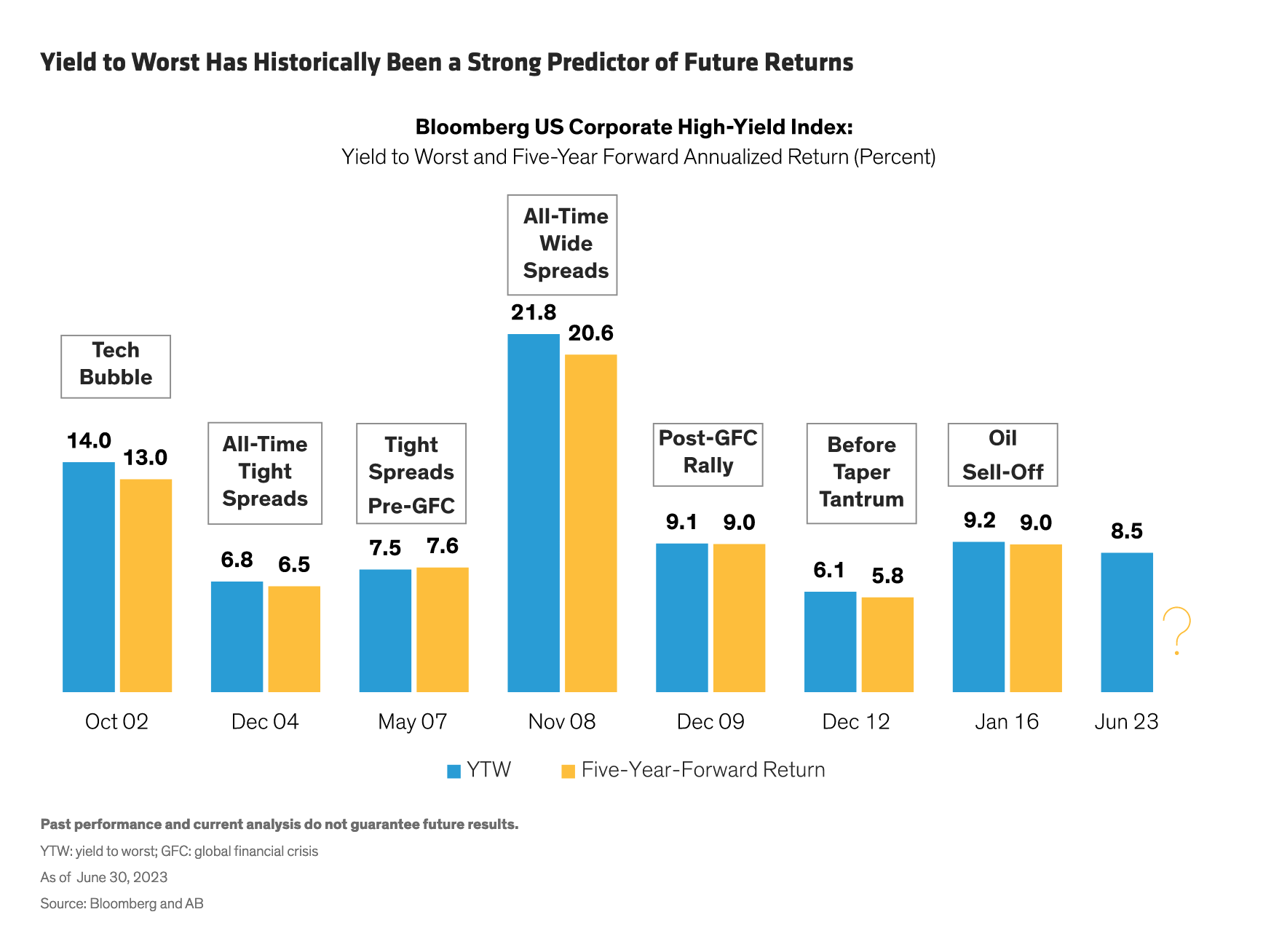

Take a longer view—an investment horizon of four or five years, say—and the picture gets even better. History shows that the high-yield sector’s yield to worst has been an excellent proxy for its return over the following five years. In fact, high yield has performed predictably, even through rough markets (Display).

The relationship between starting yield and five-year forward return held steady even during the Global Financial Crisis, one of the most stressful periods of economic and market turmoil on record. If an investor had bought high yield in May 2007 at a yield to worst of 7.5% and held onto that investment for the next five years—riding out a 36% drawdown in the high-yield market—that investor would have earned 7.6% in total return on an annualized basis.

Why? High-yield bonds supply an income stream that few other assets can match. And when high-yield issuers call their bonds before they mature, they pay bondholders a premium for the privilege. This helps compensate investors for losses suffered when some bonds default.

Instead of Sitting Out, Find Ballast in Balanced Portfolios

Despite these positive signals, many income-seeking investors remain leery of jumping on the high-yield bandwagon when spreads are merely average. But sitting on the sidelines can be a costly mistake: the yield give-up is significant today, and yields may be lower in future.

At any rate, it can be virtually impossible to time market entry. High yield is among the most resilient asset classes and tends to rebound quickly after downturns. On average, since 2000, high yield rebounded from peak-to-trough losses exceeding 5% in just five months—and as few as two. And when it did rebound, it went big. Over the 12 months following such losses, the high-yield market returned 22% on average. Reluctant investors missed out.

Instead of waiting on the sidelines, we think income investors should consider holding both government bonds and high yield in portfolios in the late stages of the credit cycle. While higher-yielding sectors, including high-yield corporate bonds, select emerging-market debt and commercial mortgage-backed securities, serve as a portfolio’s heavy income hitters, duration (sensitivity to interest rates) from Treasuries and other government bonds provides ballast.

After all, when risk assets sell off, government bonds typically rally, and vice versa. Indeed, correlated sell-offs of government bonds and risk assets have been rare over the last 30 years. Yet even when the two types of assets do decline in tandem, a barbell strategy may help to minimize the damage.

That’s why, even in the late stages of the credit cycle, we think high-yield bonds and other high-yielding assets should play a role in portfolios, helping income-seeking investors meet their goals.

About the Authors

Scott DiMaggio, Senior Vice President, is Co-Head of Fixed Income, Director of Global Fixed Income and a member of the Operating Committee. As Co-Head of Fixed Income, he is responsible for the management and strategic growth of AB’s fixed-income business. As Director of Global Fixed Income, DiMaggio oversees all of AB’s Global Fixed Income, Canada Fixed Income and US Multi-Sector Fixed Income strategies, as well as their associated investment strategy, activities and portfolio-management teams. In this capacity, he leads AB’s internal Rates and Currencies and Multi-Sector Fixed Income Research Review Committees, the primary investment policy and decision-making committees for the portfolios the firm manages. Prior to joining AB’s Fixed Income portfolio-management team, DiMaggio performed quantitative investment analysis, including asset-liability, asset-allocation, return attribution and risk analysis for the firm. Before joining the firm in 1999, DiMaggio was a risk management market analyst at Santander Investment Securities. He also held positions as a senior consultant at Ernst & Young and Andersen Consulting. DiMaggio holds a BS in business administration from the State University of New York, Albany, and an MS in finance from Baruch College. He is a member of the Global Association of Risk Professionals and a CFA charterholder. Location: New York

Gershon M. Distenfeld, Senior Vice President, is Co-Head of Fixed Income, Director of Credit and a member of the Operating Committee. As Co-Head of Fixed Income, he is responsible for the management and strategic growth of AB’s fixed-income business. As Director of Credit, Distenfeld oversees all of AB’s credit-related strategies, including all global and regional investment-grade and high-yield strategies, as well as their associated investment strategy, activities and portfolio-management teams. In this capacity, he leads AB’s internal Credit Research Review Committee, the primary investment policy and decision-making committee for all credit-related portfolios the firm manages. Distenfeld also co-manages AB’s multiple-award-winning High Income Fund, named “Best Fund over 10 Years” by Lipper from 2012 to 2015, and the multiple-award-winning Global High Yield and American Income portfolios, flagship fixed-income funds on the firm’s Luxembourg-domiciled fund platform for non-US investors. He joined AB in 1998 as a fixed-income business analyst, and served as a high-yield trader (1999–2002) and high-yield portfolio manager (2002–2006) before being named director of High Yield in 2006. Distenfeld began his career as an operations analyst supporting Emerging Markets Debt at Lehman Brothers. He holds a BS in finance from the Sy Syms School of Business at Yeshiva University and is a CFA charterholder. Location: New York

Matthew Sheridan is a Senior Vice President and Portfolio Manager at AB, primarily focusing on the Income Strategies portfolios. He is a member of the Global Fixed Income, Global High Income and Emerging Market Debt portfolio-management teams. Additionally, Sheridan is a member of the Rates and Currency Research Review team and the Emerging Market Debt Research Review team. He joined AB in 1998 and previously worked in the firm’s Structured Asset Securities Group. Sheridan holds a BS in finance from Syracuse University. He is a CFA charterholder. Location: New York