by Jeffrey Rosenberg, Sr. Portfolio Manager, Systematic Fixed Income, Blackrock

Key takeaways

- Policy tightening “cracks” appear: Bank failures mark the latest (and likely not the last) vulnerability to surface from the policy tightening cycle. Subsequent rate volatility reflects fears of widespread contagion across the economy, but also consensus positioning unwinds.

- A return to inflation fundamentals: Market and policy focus can only return to the longer-term challenge of persistent inflation if the bank run episode is effectively contained by liquidity support and implicit deposit guarantees. A liquidity crisis is more easily dealt with than solvency, but highly uncertain.

- Financial conditions in focus: Persistent inflation means that tighter financial conditions may be required to tame inflation. How much tightening the banking crisis implies for policy remains a critical unknown, but the prospects of immaculate deflation without breaking a few eggs looks increasingly implausible.

You can’t tighten monetary policy without breaking a few eggs. The recent banking crisis exposes the latest causalities of the policy tightening phase. The episode led to the sharpest rally in front-end yields since the 1987 stock market crash as markets reassessed the potential spillover of the crisis and the resulting policy response.

The US Federal Reserve (“Fed”) reacted to the regional bank failures with large liquidity provisions aimed at protecting depositors and preventing widespread economic damage, but kept monetary policy separate and on track to tackle inflation. The effectiveness of the policy response and the degree of financial conditions tightening from the crisis remain uncertain. As inflation persists well above target, policy rates may need to remain higher for longer than the market expects.

Policy tightening “cracks” appear

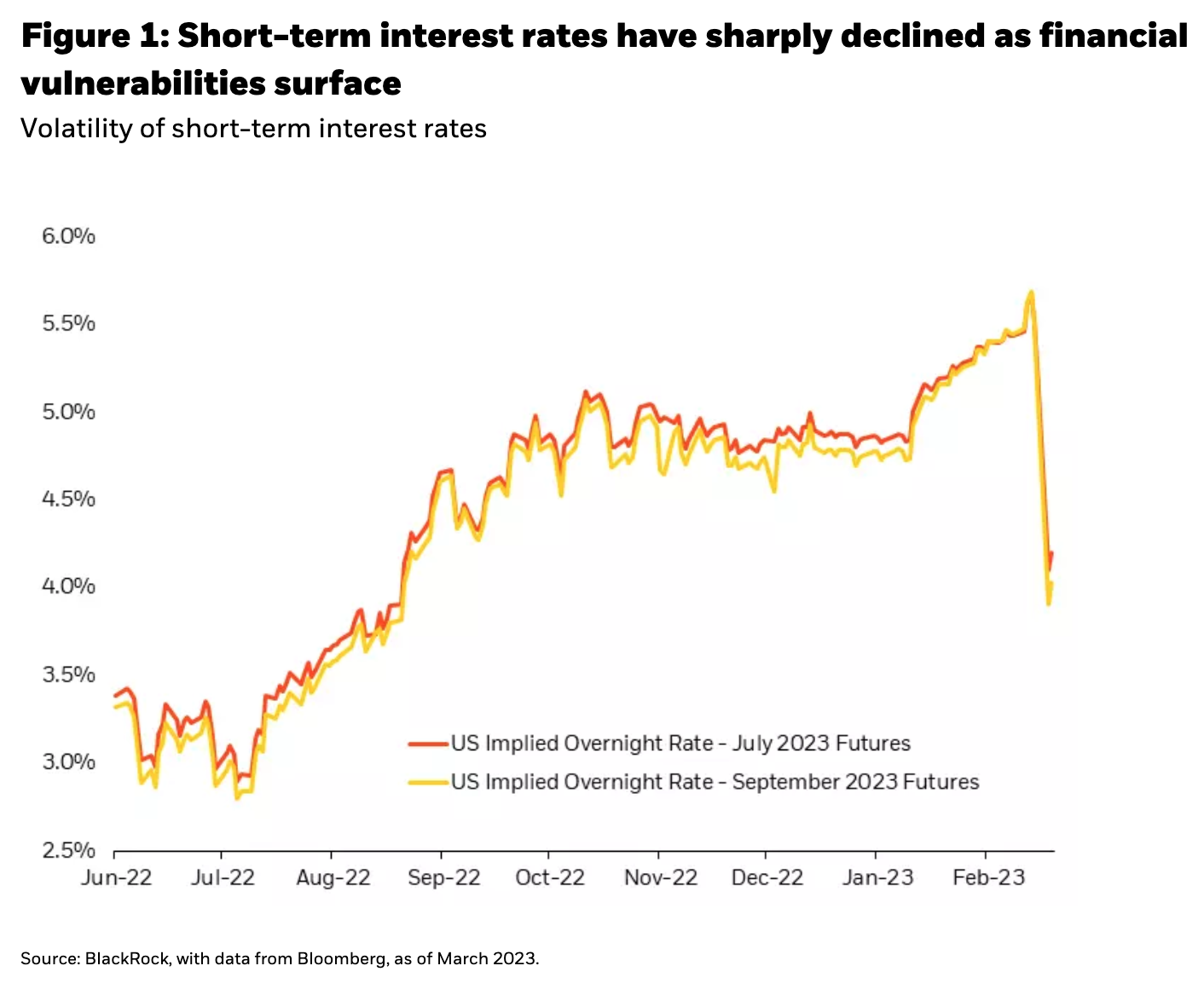

Financial stability risks that typically surface during tightening cycles are now at the forefront of investors’ minds. The first of these risks showed up last year in the UK market with the liability-driven investment (“LDI”) crisis. Similar to current fears arising from the potential runs on regional banks, LDI risks originated from an underlying mismatch between assets and liabilities. Rapidly rising interest rates left UK pension funds scrambling to match the pace of markets. These vulnerabilities likely won’t be the last revealed before central bank tightening cycles end. The risk that financial instability accelerates the traditional capitulation of Fed tightening into an accommodative policy shift is driving a rapid repricing of terminal rate expectations and historically sharp declines in short-term interest rates (Figure 1).

Unlike past episodes of financial instability when central banks faced a deficit of inflation, current financial stability concerns in the banking system operate in concert with tightening goals—albeit with a highly uncertain degree. Consequently, the recent banking crisis both in the US and in Europe leads to lower expectations for rate increases. However, fundamentally interpreting the repricing of rates policy is complicated by large capitulation of investor positions in mitigating losses from popular bets on rising interest rates.

The Fed’s recent backstopping of commercial bank liquidity and the Swiss National Bank’s support for Credit Suisse arguably exceeded market expectations. These moves may also represent a loosening of policy that poses a similar challenge to what the Bank of England (“BoE”) faced during its LDI financial crisis. The BoE resorted to purchasing bonds to calm the turmoil—a reversal of their original plan to tighten policy through the sale of bonds. However, once the immediacy of the crisis passed, and policymakers arrested the near-term threat of financial instability, the BoE resumed its tightening cycle to address the longer-term issues of persistently high inflation. The European Central Bank’s recent decision to stick with its planned interest rate increase of 50 basis points appears to successfully separate financial stability risks from inflation concerns, for the time being.

If the US policy reaction is effective at containing the bank run, we could see a similar path for the US as we did for the BoE: a temporary easing of policy to address the near-term crisis, followed by a return to the longer-term task of addressing inflation. The March Federal Open Market Committee (“FOMC”) decision to raise interest rates by 25 basis points appears to walk the line between maintaining a focus on inflation fighting credibility while acknowledging the financial stability concerns.

A return to the inflation fundamentals

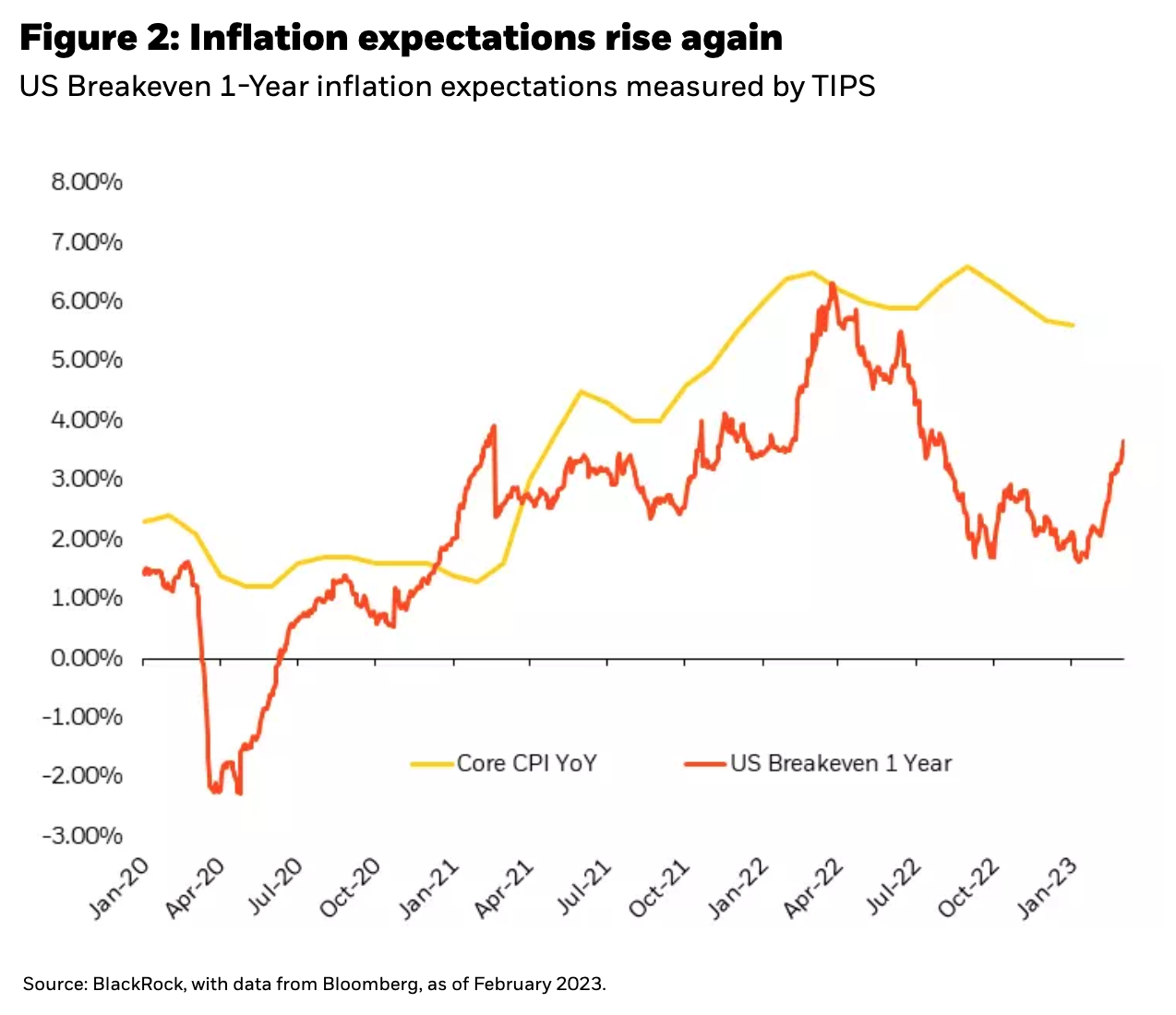

After peaking in late October and early November, inflation fears began to ease as headline and core measures of inflation finally receded from their local highs. Our Winter 2023 Outlook in December asked the question, “Now what?”— suggesting that taming inflation may take longer than markets expect. The following months brought stickier-than-expected inflationary data and a resilient job market to validate that perspective, but the path has been volatile. Rapid shifts in inflation expectations are reflected in the near-term breakeven inflation rate shown below.

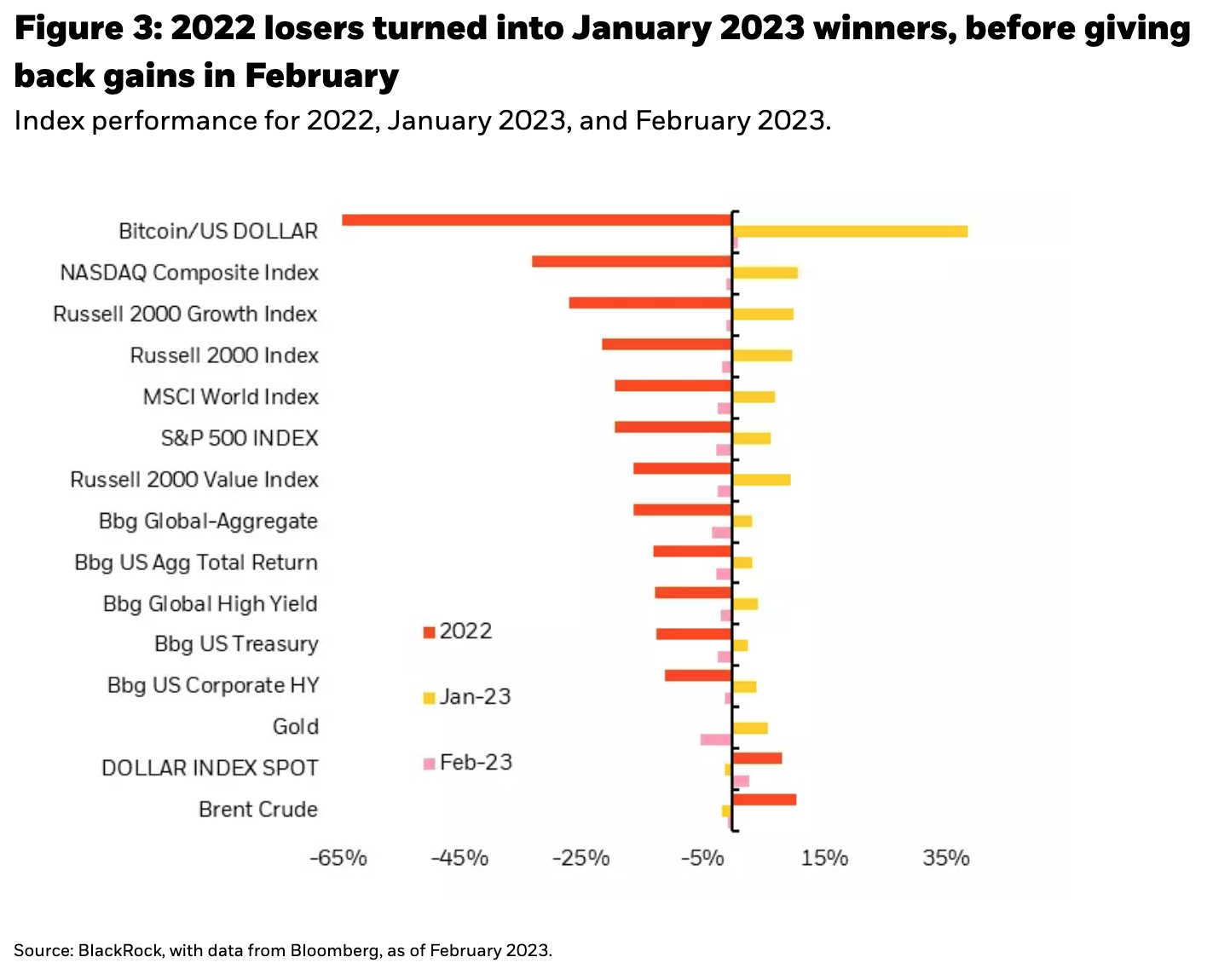

Figure 2 reveals the steady decline in inflation expectations after COVID-induced supply side price surges began to subside. Peak inflation arrived in October of 2022 and the market narrative shifted to “inflation was indeed transitory, and the Fed’s policy tightening has been successful.” With this perceived success, the market could move on to focus on “soft landing” (and briefly “no landing”) scenarios. The result of this shift in the market narrative was rising stock and bond prices. This was a rapid about-face for markets, as securities that registered some the biggest losses in 2022, became the biggest winners at the start of 2023 (Figure 3).

Volatility is the consequence of moving from forecast-dependence to data-dependence

Dramatic swings in both the market narrative and market performance reflect rapid shifts in Fed policy expectations. This volatility has been exacerbated by a recent evolution in Fed policy to reduce its reliance on forecasts for inflation and instead rely on realized inflation. This means that short-run changes in inflationary data have an outsized impact on policy expectations, and as a result, market behavior.

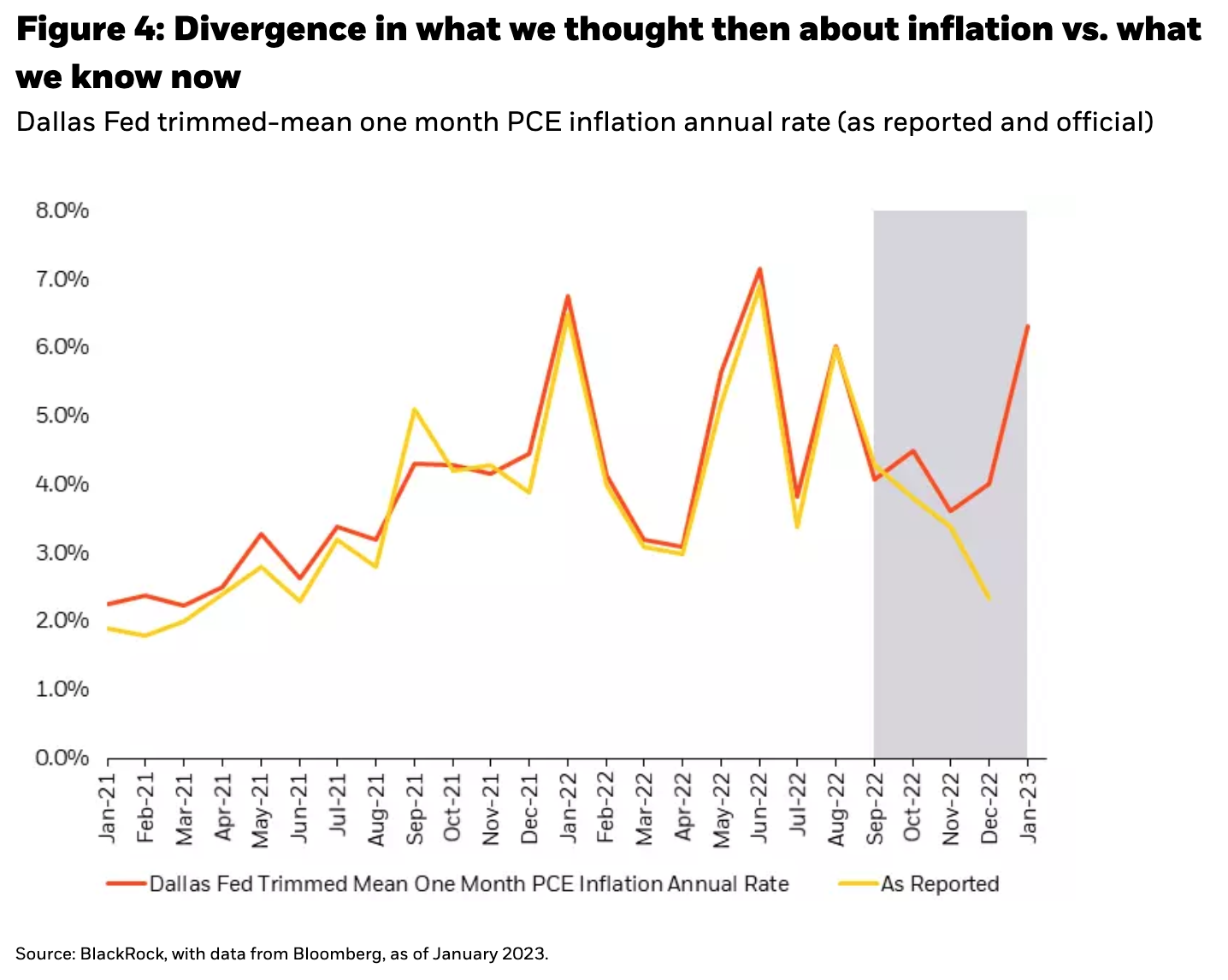

This volatility is further intensified by the fact that data estimates of realized inflation are just that—estimates. As a result, these readings are subject to later revisions. Recent revisions to prior inflation prints have had an outsized impact on the changing perception of progress towards taming inflation. Figure 4 shows the recent divergence between initially reported and official revised figures of the Dallas Fed trimmed-mean Personal Consumption Expenditures (“PCE”) inflation measure.

Progress in reducing inflation that was first reported last fall turned out to be overstated as initial inflation readings were revised higher. Following these revisions, reports on employment, wages, monthly inflation prints, and business surveys each reinforced the idea that inflation remained stickier than what was previously expected.

The key issue underpinning persistent inflation remains labor market tightness and wage inflation. However, compositional shifts can heavily distort measures of wage inflation, with Average Hourly Earnings (“AHE”) being the most susceptible to this issue. The Atlanta Fed’s Wage Growth Tracker is arguably the best measure of wage inflation as it controls for compositional changes. This measure ticked back up to its highest level since June, unwinding all of the previous perceived improvements in wage inflation. Survey data pointing to continued labor constraints and elevated job openings relative to unemployment reinforce the idea that labor markets remain too tight for inflation to return to the Fed’s 2% target. Fed Chairman Jerome Powell took note of this in his March congressional testimony, reminding markets of the Fed’s determination to continue slowing the economy to bring down inflation and again repeated those concerns in the March FOMC press conference.

The more that policymakers and market participants believe that higher rates are needed to slow the economy, the longer and further the tightening cycle may need to go. As this plays out, the pressure on bond market returns may reemerge as market pricing for inflation and terminal rates catches up to stubborn inflationary data.

Bond yield vs. bond ballast: decoding the underlying dynamics

Bonds have historically played a critical role in portfolios for their ability to go up when stocks go down. The recent banking crisis saw that property on display again. Over the past thirty years, bond ballast acted as a reliable portfolio diversifier and the anchor to 60/40 portfolios and risk parity strategies. Behind that success stood an aspect of the global economy that’s now missing: too little inflation. Bonds could effectively diversify equity risk because of the expectation for highly accommodative monetary policy to counteract recessionary (growth) shocks. And the large magnitude of that policy accommodation expectation was due to an environment of persistently below target inflation.

With little concerns over inflation overshooting in the decades leading up to COVID-19, monetary policy benefitted from a “divine coincidence.”1 Under this structural characteristic, shortfalls in economic growth and inflation could be addressed at the same time with the same tool of accommodative monetary policy. But today – as in the 1970s – 1990s – too much inflation now means that policymakers face a tradeoff between their growth and inflation objectives. Stabilizing growth no longer implies stabilizing inflation. This tradeoff limits just how accommodative policymakers can be when faced with a growth shock.

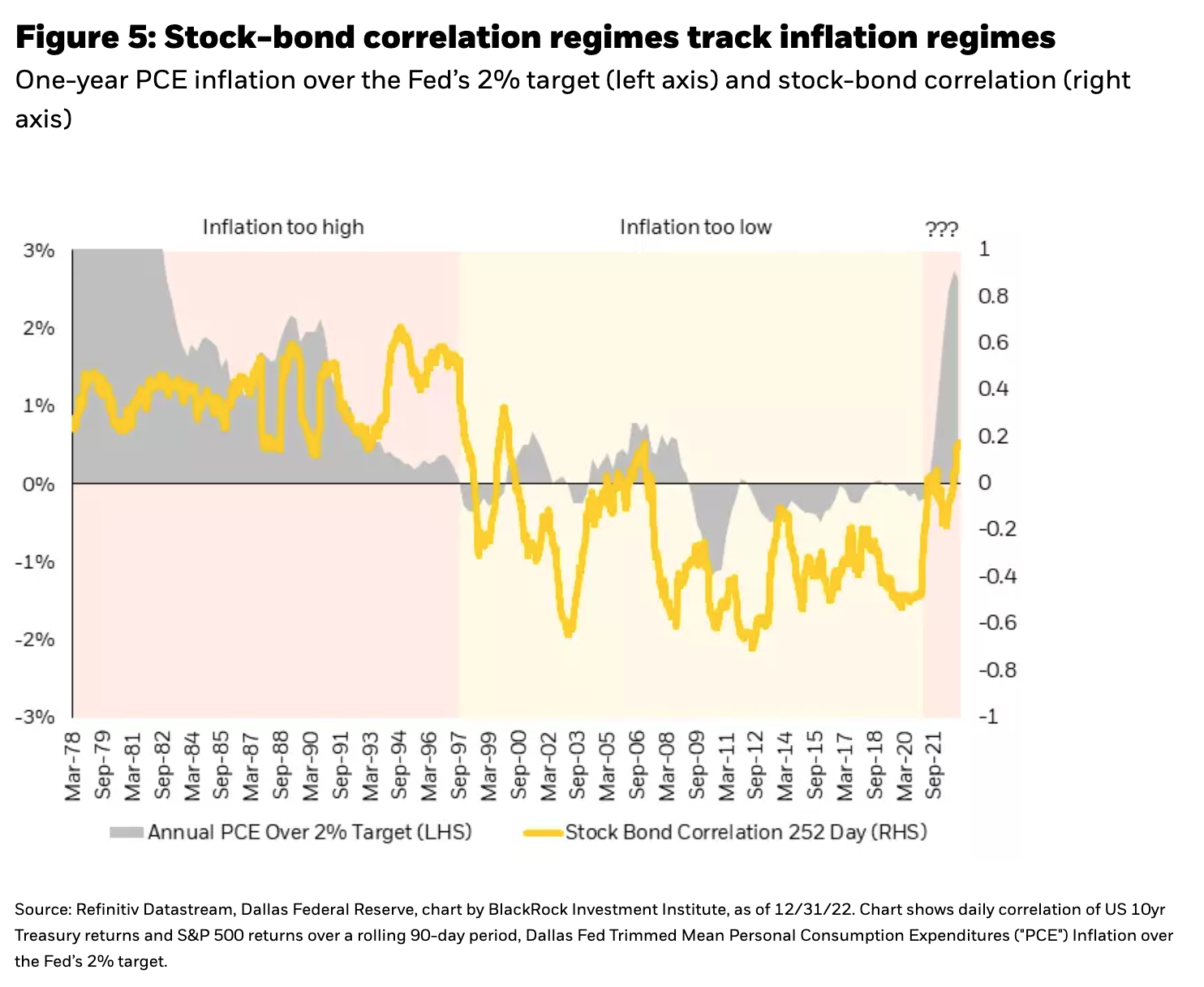

Today, the global economy faces an environment of too much inflation. That ends the “divine coincidence” and puts inflation goals at odds with growth. The result of this dynamic is a measurable shift in stock-bond correlation away from persistently negative readings when inflation was too low and towards positive readings that coincide with inflation being too high (Figure 5).

But as recent experience during the banking crisis just showed, an expectation for a less reliable negative stock-bond correlation doesn’t relegate bonds to playing no role in portfolio diversification. The recent volatility with regional banks in the US and large systemic banks in Europe saw a generalized flight to quality. Shorter term interest rates rallied the most. The shift in rates represented some of the largest one- and two-day changes on record, exceeding the Global Financial Crisis (“GFC”) and just behind the 1987 crash. That was partially due to very large unwinds of short interest rate positions. But it also reflects expectations that tightening in the financial sector will do more of the heavy lifting of slowing inflation so that Fed policy rates won’t need to go up as far.

However, the persistence and size of the rally ultimately will depend on the strength of any expectation for a shift to accommodative Fed policy. If inflation remains too high, the expectation for accommodative policy will be more tempered than in the past—either through the data realization or directly by the Fed’s messaging.

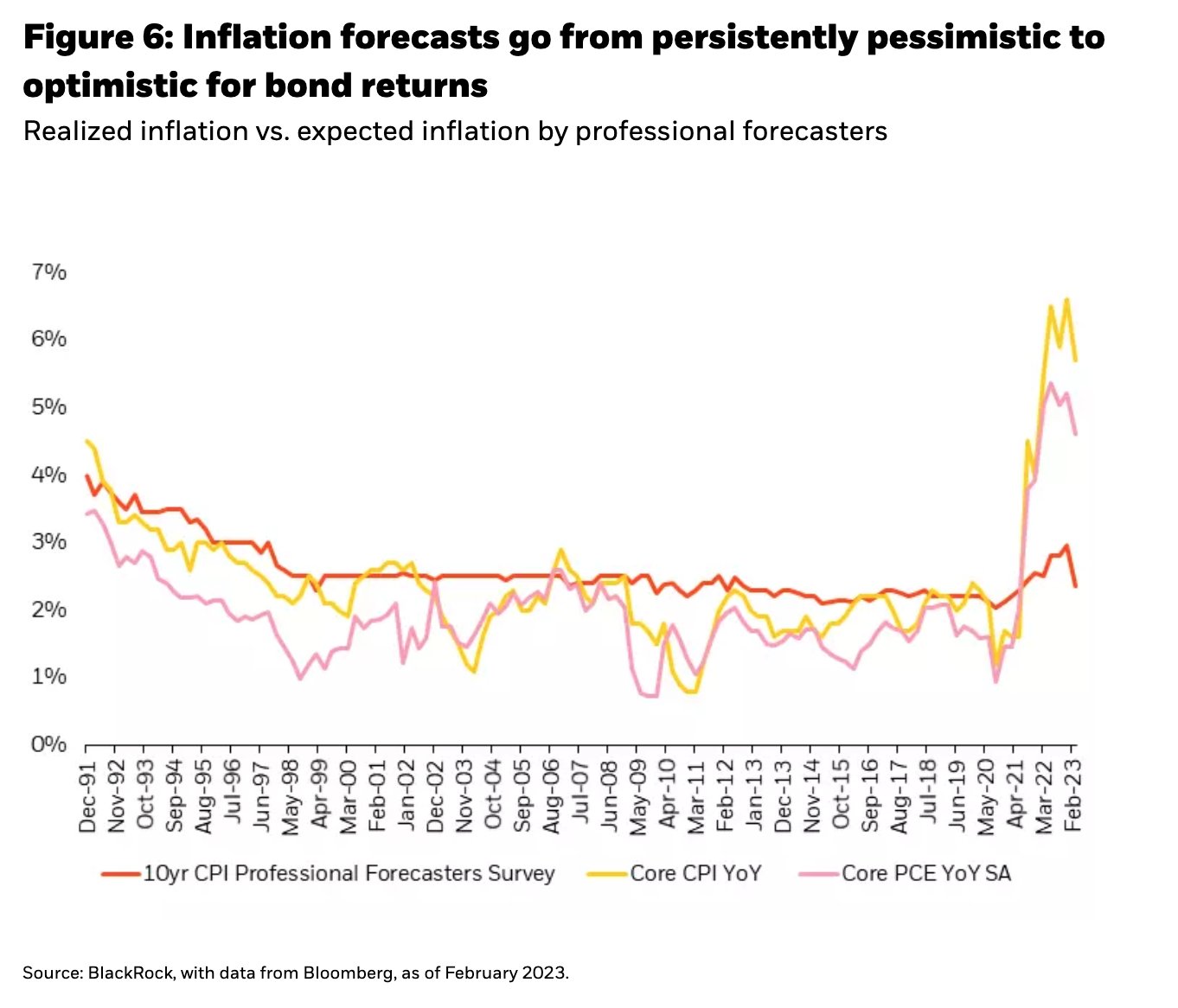

Forecasting inflation is hard

This raises the additional role that expected vs. realized inflation plays in the performance of bonds. The current regime for bonds is very different from what existed in the past thirty years. Figure 6 highlights realized vs. expected inflation as measured by the survey of professional forecasters. During the period of “too little” inflation that characterized the last thirty years of bond returns, forecasted inflation was persistently higher relative to realized inflation. As a result, bond returns were higher in real terms as starting yield compensation was greater than necessary for the level of realized inflation. This generated both real income and capital gains from falling real rates and falling risk and inflation term premiums as inflation missed to the downside.

Today, we see the opposite conditions. Inflation forecasts have been and continue to be persistently below realized inflation readings. This has led to both falling real bond returns (inflation-adjusted returns) and capital losses as rising nominal rates reflect the impact of higher inflation and the potential need for higher interest rates. That dynamic may prove temporary, allowing the pre-COVID structure of too little inflation to return. However, until it does, higher yields come with higher volatility (read risk) and that reflects the unsettled path for inflation.

Implications for investors

The key portfolio implication is that until inflation uncertainty subsides, we may not see the return of a reliable negative stock-bond correlation and bond returns may be challenged again from rising rates. Term premiums continue to fail to price in the possibility of more persistent inflation, leading to highly inverted yield curves offering the best opportunities in the shortest maturities.

Conclusion

You can’t tighten monetary policy without breaking a few eggs. This lesson grabbed the focus of markets following the recent bank failures, driving the sharpest rally in front-end yields since the 1987 stock market crash. Policymakers quickly stepped in with measures aimed at protecting depositors and stemming the spillover of the crisis across the broader economy. If these measures effectively stop the contagion of the banking crisis, the focus of central banks and markets may shift back towards the underlying task at hand: inflation that remains well above central bank targets.

The more that policymakers and markets believe that higher rates are needed to slow the economy and bring down inflation, the longer and further the tightening cycle may need to go. This will have potentially profound implications on the 60/40 portfolio, putting pressure on bond returns as terminal rates and market pricing of inflation catches up to stubbornly high price pressures. As we look beyond the “cracks” of policy tightening, the longer-term outlook remains in question as the inflation fight continues.

*****

Copyright © Blackrock