It was quite a weekend...

Silicon Valley Bank’s collapse on Friday was a result of bad market risk management, concentrated funding, and moral hazard, according to Alfonso Peccatiello, Macro Strategist at The Marco Compass. In his analysis, Peccatiello attempts to answer the questions regarding the bank’s downfall, the spillover risks, and the Fed and markets' reactions.

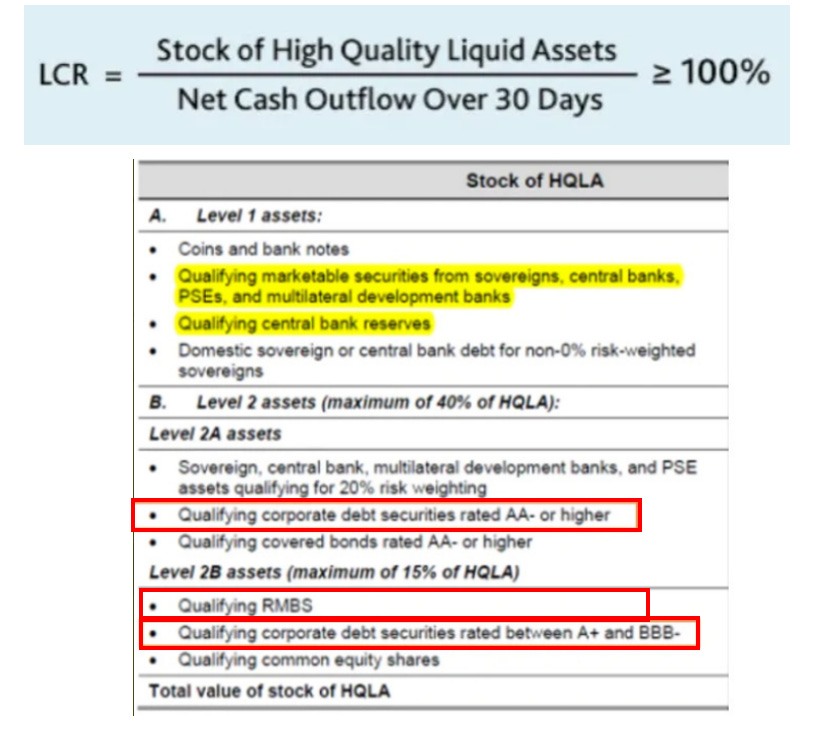

Post-GFC, regulators forced banks to hold an amount of high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) to meet a stressed outflow of deposits for 30 days. These include Reserves at the Central Bank, Treasuries, corporate bonds, and Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) to a certain extent. Banks all over the world have thus filled their balance sheets with trillions of bonds, but holding large amounts of bonds also comes with risks such as interest rate risk.

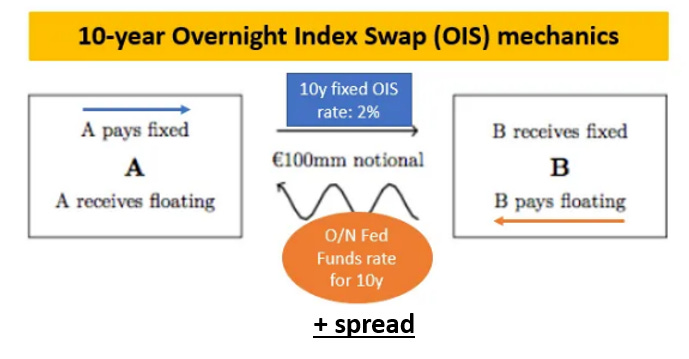

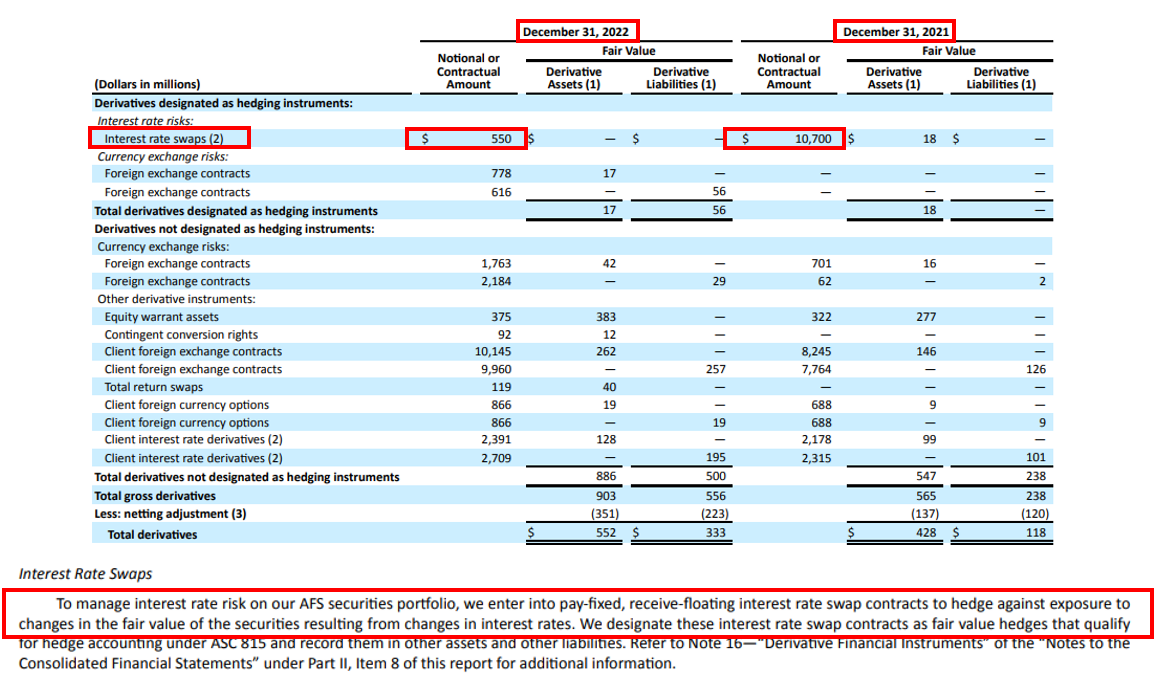

Banks hedge the lion share of the interest rate risk coming from their HQLA investments by entering into an interest rate swap, paying away a fixed yield and receiving variable payments in exchange, allowing them to hedge the interest rate risk and earn a small spread on their HQLA portfolio.

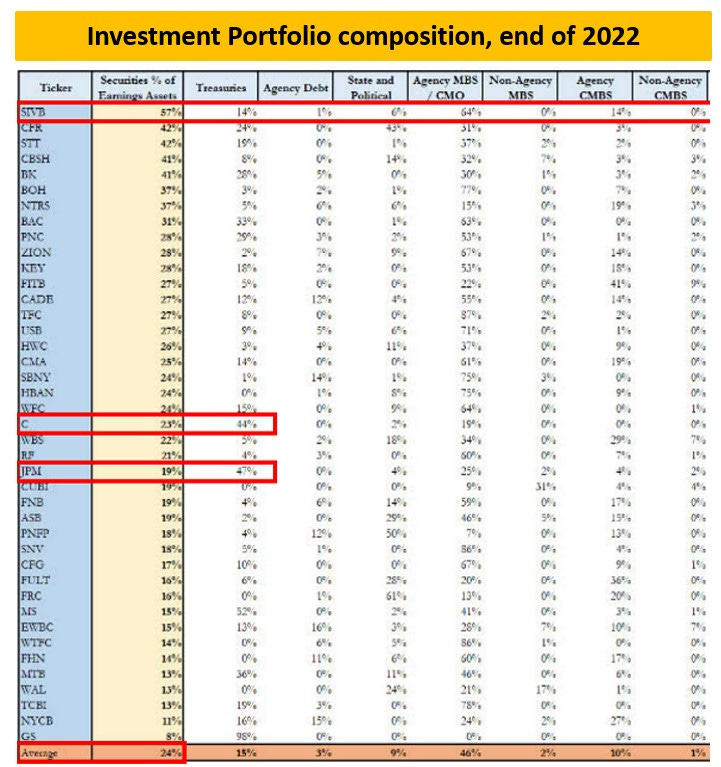

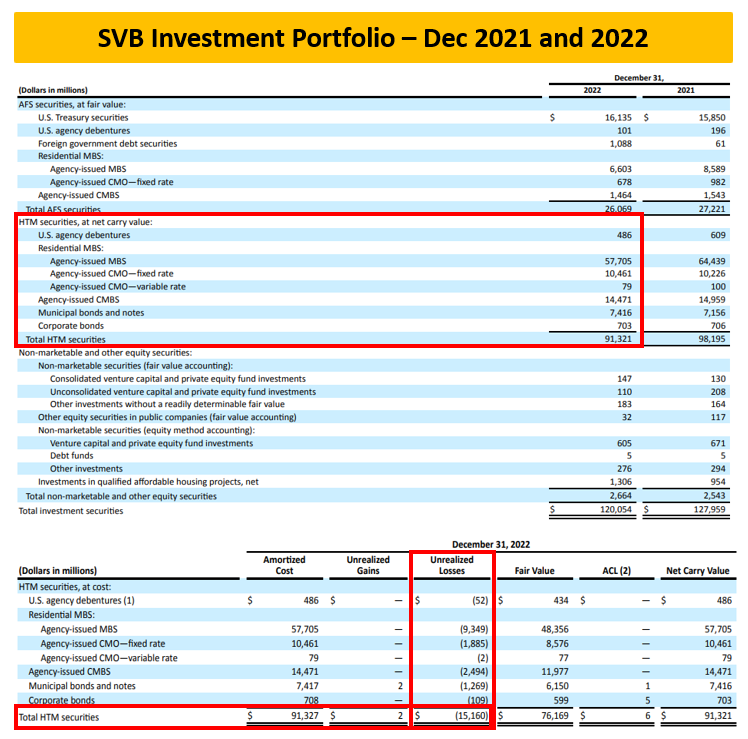

SVB had a gigantic investment portfolio, comprising 57% of total assets (average US bank: 24%), and 78% was in Mortgage-Backed Securities (Citi or JPM: around 30%). Most importantly, they did not hedge interest rate risk at all.

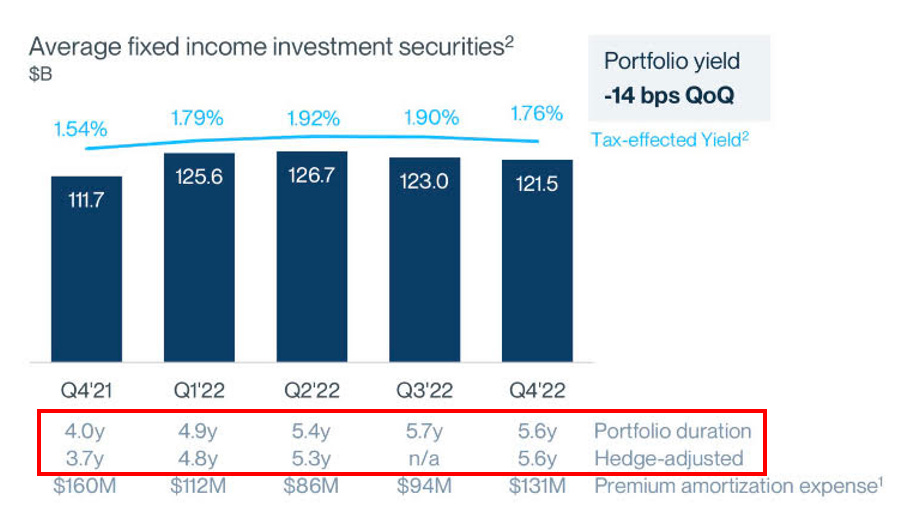

The duration of their huge portfolio before and after interest rate hedges was the same, which means that effectively there were no hedges.

This means SVB was not applying basic risk management practices, exposing its investors and depositors to a gigantic amount of risk. Economically speaking, a $120bn bond portfolio with a 5.6y non-hedged duration means that every 10 bps move higher in 5-year interest rate lost the bank almost $700 million.

As the tech/IPO boom faded, deposits stopped coming in 2022. Recently, depositors started taking their money away, forcing SVB to realize these huge losses on bond investments to service deposit outflows. The concentrated nature of the deposit base and awful risk management meant SVB went bankrupt very quickly. Many people are now calling for a blanket bailout, but the evidence that moral hazard was at play is too big to be ignored. Companies go bankrupt; it happens. Perhaps it was just huge incompetence at work, or bad luck. But the evidence that moral hazard played an important role is hard to ignore.

Peccatiello provides three interconnected facts which are hard to ignore: HQLA investments can be booked either under the Available For Sale (AFS) or Held To Maturity (HTM) accounting regimes. AFS investment unrealized gains/losses do not hit the P&L of the bank, but they do show up in the capital position of the bank. Booking bonds in HTM instead prevents gains/losses from showing up at all. SVB had a gigantic bond book and made an unusually large use of the convenient HTM accounting regime. The unrealized losses as per Dec 2022 in the HTM portfolio alone amounted to $15 billion, enough to wipe out the bank’s capital but conveniently hidden through the abnormal use of this accounting trick. You don’t book $90 billion of unhedged bonds in HTM by mistake or incompetence; this is moral hazard.

The reason why SVB could get around with this terribly risky business model was its size. Banks with assets below $250 billion are not subject to tighter regulatory scrutiny like big banks. No liquidity ratios, net stable funding requirements, and light stress tests force banks to diversify their funding base. This allowed SVB to run wild with its investment portfolio and funding base concentration.

SVB’s management repeatedly lobbied to increase the cap for lax regulatory scrutiny and conveniently remained 20-30 billion below the $250 billion threshold, indicating the presence of moral hazard.

Peccatiello argues that moral hazard played an important role in SVB’s downfall. He believes that we should not reward moral hazard, and companies go belly up - it happens. Despite this, many people are calling for a blanket bailout. Peccatiello suggests making only uninsured depositors whole, considering the evidence of moral hazard.

Peccatiello notes that SVB isn't the only bank with assets below $250 billion benefitting from this. However, SVB's management repeatedly lobbied to increase the cap for lax regulatory scrutiny and conveniently remained 20-30 billion below the $250 billion threshold. It is hard to deny a decent amount of moral hazard was at play here.

Peccatiello questions whether the government should fully bail out SVB or only make uninsured depositors whole. The question remains as to whether SVB is a canary in the coal mine for a systemic banking crisis.

As for the Fed reaction and market impact, it remains to be seen.

*****

UPDATE as of March 12, 2023 - 7:11PM:

SVB Depositors Will Get All Their Money After Frantic Weekend

-

- Both insured and uninsured deposits will be made available

- No losses at Silicon Valley Bank will be borne by taxpayers

US Races to Contain SVB Fallout: Bloomberg Live Blog

-

- US says all SVB deposits safe, creates backstop for banks

- NY takes control of Signature Bank; depositors to be made whole

- US 2-year yield tumbles while stock futures gain

- Ackman praises US action, Goldman sees no March Fed hike

- Sunak says UK financial system ‘sound,’ to comment on SVB

Fed Half-Point Hike Looks Less Likely as Financial Risks Flare

-

- Yields on two-year Treasury notes tumble in Asian trading

- Slower pace of hikes would allow time to assess fallout

*****

For Alfonso Peccatiello's full scope, visit The Macro Compass:

Footnotes:

1 adapted from source: (Alf), Alfonso Peccatiello. "Banking Crisis?" The Macro Compass, 12 Mar. 2023, themacrocompass.substack.com/p/banking-crisis?utm_source=substack&utm_medium=email.