by John Mauldin, Mauldin Economics

Additional Headwinds

No Recession in the Jobs Data

Price over Volume

Cold Weather, Travel, and SIC

These weekly letters, of which I’ve now written well over 1,000 (plus 7 books and multiple papers and articles), are generally about two broad topics: the economy and the financial markets. While related, these aren’t the same. Good news for one can be (and often is) bad news for the other.

I explained my economic forecast in recent letters. Briefly, I think the Fed will raise rates another 1‒2 times by 25 bps, taking the fed funds rate to my original target last year of 5%+. These hikes are beginning to (slowly, step by step, item by item) suppress demand. This will continue because they need to stomp inflation. It will probably push the economy into recession. I don’t expect anything like 2008 but the odds of getting through this painlessly are quite low.

So economically, I’m on the slightly pessimistic side for 2023. Today we’ll talk more about my market outlook for the next year or so. The answer may be disappointing if you want me to be either bullish or bearish. I am neither, at least for now. My best guess is we’ll have kind of a “muddle through” year, featuring moments of both terror and euphoria on the way to relatively minor change.

That doesn’t mean we’re out of the woods. As you’ll see, 2023 could be the pause that refreshes… before a much worse 2024.

“The Supreme Overconfidence Bubble”

GMO co-founder Jeremy Grantham has been in this business longer than most. That doesn’t make him perfect, but he’s seen a lot of market history up close and personally. His strategy has long been to simply avoid buying during overpriced asset bubbles, and particularly during what he calls “superbubbles.” Do that successfully and everything else will work out.

The key, then, is to correctly identify these superbubbles. Easier said than done, especially when you’re in the middle of one. Historically, he says there were five in the last century: the US stock market in 1929 and 2000, the Japanese stock market in 1989, the US housing market in 2006, and Japanese real estate in 1989. All ended with major, extended pain. Jeremy says the US stock market is currently in the middle of another such superbubble.

But note carefully: in the middle of a superbubble. In his latest letter Jeremy talks about how this one started losing air in 2022. While not fully deflated, the superbubble is at least smaller now, which means risks are somewhat lower than they were a year ago. Yet the path forward is still dangerous. Here’s a quote from Jeremy’s latest report. Emphasis mine. (Over My Shoulder members can read it in full here):

“The long list of things that have gone wrong—that could interact and cause some component of the system to break under stress (perhaps an unexpected component)—makes for depressing reading. The complexities have multiplied, and the range of outcomes is much greater, perhaps even unprecedented in my experience. That having been said, the odds of a major US market decline from here cannot be as high as they were last year. The pricking of the supreme overconfidence bubble is behind us, and stocks are now cheaper. But because of the sheer length of the list of important negatives, I believe continued economic and financial problems are likely. I believe they could easily turn out to be unexpectedly dire. I believe therefore that a continued market decline of at least substantial proportions, while not the near certainty it was a year ago, is much more likely than not.

“My calculations of trendline value of the S&P 500, adjusted upwards for trendline growth and for expected inflation, is about 3200 by the end of 2023. I believe it is likely (3 to 1) to reach that trend and spend at least some time below it this year or next. Not the end of the world but compared to the Goldilocks pattern of the last 20 years, pretty brutal.”

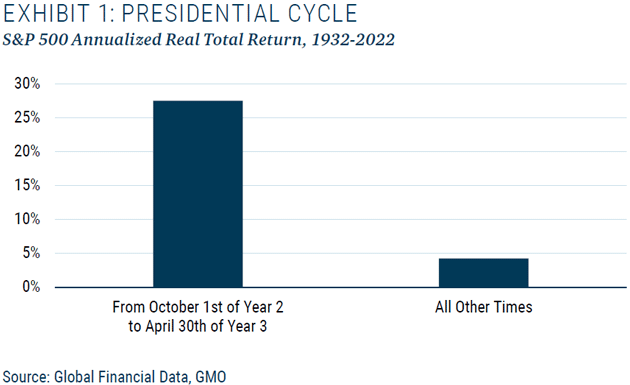

He goes on to describe several factors that could delay the reckoning past 2023. One is the presidential cycle. Since 1932 the 7-month period from October of a president’s second year in office through April of the third year has delivered the same stock market performance as the other 41 months. We are now in that period.

Source: GMO

Why would this be? All presidents want to be re-elected, or have their chosen successor elected, and they also know economic policies need time to produce politically beneficial effects. This is the period when the market notices such efforts ahead of the next election.

That’s the theory, at least. It won’t necessarily be the case this time. But statistically, it suggests investors may see reasons to buy (or at least avoid selling) in early 2023.

That’s not the only short-term bullish influence. Here’s Jeremy again:

“Other factors suggesting a long or delayed decline include the fact that we start today with a still very strong labor market, inflation apparently beginning to subside, and China hopefully regrouping from a strict lockdown phase that has badly interfered with both their domestic and international business…

“One important contributor to the resilience of the economy so far has been the enormous accumulation of excess cash that resulted from the COVID-19 stimulus. Different methods of estimating these excess savings give slightly different figures, but most analysts put the peak of excess savings at $2‒3 trillion in late 2021. This excess savings balance has been slowly drawn down over the course of 2022, but less than half now remains. Once it runs out, by some estimates around mid-year, this particular support for the economy will be gone.”

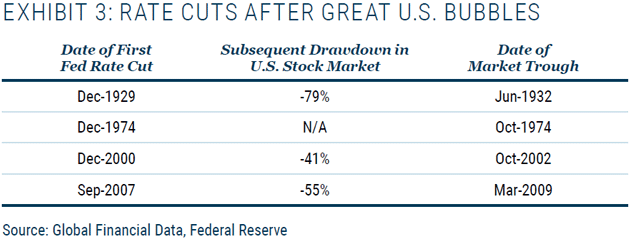

While that’s not an “all clear,” it may mean we’ll see further gains before sliding to a final bottom. Jeremy notes many bullish investors are excitedly looking forward to the Fed cutting rates. Yet in 1929, 2000, and 2007 the bulk of market declines occurred after the first rate cuts. The same might have happened in 1974 had inflation not been surging at the time.

Source: GMO

Further to that point, markets usually don’t bottom until 7‒8 months after a recession starts, which hasn’t officially happened yet. I keep saying these are weird times and we may have a weird recession.

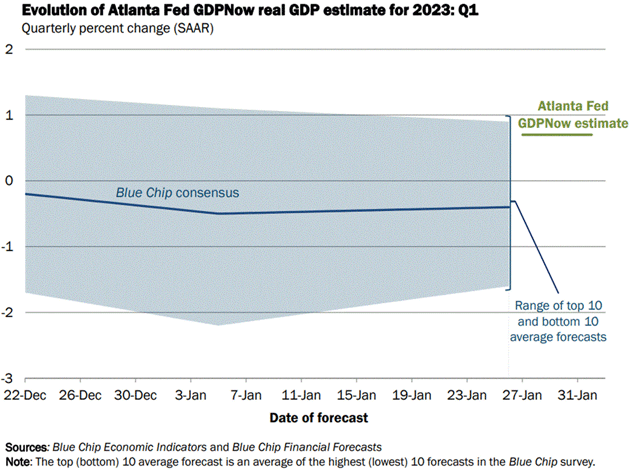

The Atlanta Fed publishes a running GDP “Nowcast” estimate for the current quarter based on a data model. Their chart also shows the Blue Chip economist consensus forecast. I have been following this for a while, and I don’t remember seeing their modeled forecast above the Blue Chip consensus like this. Probably it’s happened, but I just don’t remember. The Atlanta Fed is at 0.7% for the first quarter, based on data that has been released. The economist forecast shows roughly a negative -0.3%, although that was a week ago and the range was wide from ~ +1% to -1.5%.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta

In any case, there’s plenty of time for further GDP and market gains before recession arrives, the Fed starts cutting, and markets finally bottom. If so, a mildly bullish near-term stance is reasonable… assuming you’re nimble and prepared to exit before the next downturn. Most investors aren’t.

Additional Headwinds

This week the Federal Open Market Committee decided to raise rates another 0.25%, a notch down from December, which was itself a retreat from a string of 75-point hikes. This encouraged those who think the Fed will pause soon and then start cutting rates later this year.

I’m not buying it. I have clearly been in the “higher for longer” camp for a long time and today’s gonzo employment numbers just reinforce that. It will certainly encourage the soft landing proponents but do nothing to push the Fed to loosen, absent a drop in real inflation.

January was a pretty good month for markets, maybe in anticipation of this Fed action. But you could also argue it was a bounce from oversold conditions spurred by tax-loss selling in December. In a recent strategy note, Morgan Stanley’s Michael Wilson pointed to similar scenarios in 2000‒2001 and 2018‒2019. The first of those is a better match to today’s Fed cycle, and that rally faded quickly.

Wilson goes on to the more fundamental problem, which is that economic problems are starting to hit earnings and profit margins.

“Growth is not just modestly slowing but is, in fact, accelerating to the downside. 4Q earnings season is confirming our negative operating leverage thesis (see more below). Importantly, margin headwinds are not just an issue for technology stocks. As we have noted many times over the past year, the over-earning phenomenon this time was very broad as indicated by the fact that ~80% of S&P industry groups are seeing cost growth in excess of sales growth.

“As a result, we remain highly confident in our well below consensus EPS forecasts of $195 for this year. In fact, we are now leaning more toward our bear case of $180 based on the margin degradation so far and what our earnings models are projecting. We think it's important to note that typically when forward earnings growth goes negative, the Fed is actually cutting rates. That's not the case this time around... an additional headwind for equities.”

Stock prices are (theoretically) the discounted present value of forecasted future earnings. Whether you are paying a fair price depends on assumptions about earnings, interest rates, and inflation, all of which are inherently uncertain. That’s why stocks have profit potential. You are taking a risk when you buy—hopefully an informed, prudent risk, but always a risk. Always.

What reason is there to think earnings will rise or at least hold steady from here? Well, let’s first ask what are earnings? They are (ignoring a bunch of accounting nuance) the difference between a company’s revenue and its costs. Those are both moving targets. Revenue can rise and fall, as can costs.

Many companies have been doing well because they’ve had pricing power. Inflation gave them cover to raise prices (or, more subtly, shrink package sizes) while consumers flush with stimulus cash and higher wages didn’t complain too much. (That’s not all consumers by any means; many still struggle to afford the basics. I’m talking about averages here.) We can see this in profit margins, which have widened nicely for many companies.

Wilson’s team at Morgan Stanley thinks this is about to turn the other way.

“We think margin pressure is what will drive the downside we are expecting in 2023 earnings—as inflation falls companies will struggle to cut costs as quickly as pricing power erodes. We have already seen margin trouble for a number of companies that have reported 4Q earnings and we only expect the issue to heat up as we move further into the year. EBIT margins for 2023 have fallen 1.2% for the S&P 500 since the end of last year. The industry groups that have seen the biggest margin downside are Autos, Energy, and Capital Goods. Net margins for 2023 have fallen 1.5% for the S&P 500 since the end of last year.”

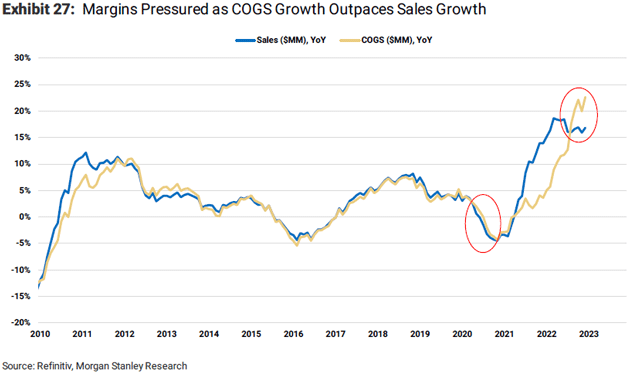

They share this chart, which should greatly concern anyone who thinks S&P 500 earnings will grow from here.

Source: Morgan Stanley

The lines show year-over-year percent change in sales (the blue line) and Cost of Goods Sold (COGS), the yellow line. Note how they tracked closely from 2010 until 2021. Then sales growth suddenly began far exceeding cost growth. But the lines recently crossed again—not good if you’re holding an index fund. And seeing cost growth accelerate while sales growth flattens is ominous, too.

Note, of course, we’re looking at the whole market here. Individual company results can vary, which means investors may still have opportunities. But they’ll be harder to find and more people will want to own them.

No Recession in the Jobs Data

The jobs data was gonzo, depending on whether you look into the details. US payrolls rose 517,000 plus positive revisions to prior months. The unemployment rate fell as labor force participation rose with more workers coming off the sidelines.

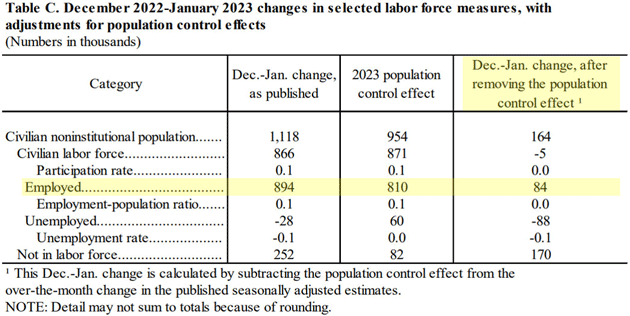

The Household data looked huge at 894,000 jobs added. Except that the BLS made a normal “adjustment” to the population control data which actually added 810,000 of those jobs. From their website (courtesy of a quick analysis by Barry Habib and emails back and forth):

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

That puts the household survey much more in line with the ADP report of 106,000 jobs this week. Seasonal adjustments also had a big effect this time. Jobs growth, while still strong, isn’t as strong as January’s report suggests.

Price over Volume

Businesses use technology in all kinds of profit-enhancing ways that aren’t necessarily obvious to consumers. Airlines, for example, have long used “yield management” programs to set ticket prices based on all kinds of factors. That’s how you can have an entire planeload of 200 people paying 200 different prices to go on the same place.

That kind of technology is getting far more sophisticated and becoming common in other industries. Like the airlines, they are trying to make every individual customer pay as much as possible without losing the sale.

The result is companies can increasingly maximize sales via price instead of volume. Sometimes this is by necessity, too. If the supply chain only lets you produce a limited number of widgets, you look for ways to squeeze as much revenue as possible from each one.

My longtime friend Samuel Rines, now of Corbu, wrote about this in a perceptive piece last week. He walked through a long list of company announcements from various industries, all saying the same thing in various ways: “Our costs are rising but we’re successfully raising prices even more.” At railroad Norfolk Southern (NSC), for example, freight unit volume dropped 1% in Q4 but revenue per unit rose 15%. They carried less cargo but made more money.

That is, of course, a wonderful state of affairs for these companies. But can it continue? This is the kind of thing that, in a free market, draws competitors who find ways to offer consumers a better deal. That may yet happen in some of these cases, but it’s not happening quickly. Companies are learning they can raise prices almost at will.

Back in 2019 I reviewed my friend Jonathan Tepper’s then-new book, The Myth of Capitalism. It described how lack of competition was leaving once-crowded industries dominated by one or two giant players. Years of artificially low interest rates helped. I said this:

“Today’s capitalism has a contradiction that is increasingly hard to ignore: lack of competition in key markets. That’s a problem because competition incentivizes producers to get more efficient and reduce prices for consumers. Without competition, you end up with bloated monopolies that may be highly profitable for the owners, but don’t serve the greater cause of economic growth.”

Four years later, I think that’s exactly where we are. That isn’t the capitalism we grew up with, it isn’t sustainable, and it’s ultimately inconsistent with a rising stock market. But it’s working for now and may continue a while longer.

Will new rail companies form to price compete with Norfolk Southern? It would take billions of capital and then they would have to slowly gain market share and somehow find space on the existing rails.

But here’s the problem. The employment numbers give the Fed room to hike more IF:

- The headline unemployment rate stays under 5%. As of now it’s at all-time lows, for a variety of reasons we have discussed.

- Inflation is still above 2‒3%, which it will likely stay for a few quarters. It will fall eventually but until then, all things being equal, there is nothing to deter the Fed from Powell’s current tightening regime.

- Wage growth continues. Friday’s data showed earnings up again. The labor market is tight. If it stays this way, we should see AT LEAST two more rate hikes, depending on inflation.

The Fed needs to see employment stable. That and inflation are their only concerns now. They do NOT give a (insert your metaphor here) about the stock market and only marginally about credit markets in today’s inflationary environment. Mortgage rates in the 5% range? They are perfectly fine with that.

Therefore, I believe the Fed is going to keep rates high(er) for some time and continue quantitative tightening as assets roll off the balance sheet. There will be no rate cuts this year, barring some really serious event.

The Fed is essentially deleveraging the entire economy, much of which depends on that same leverage. In one sense, they are pushing us toward the “Great Reset” global debt restructuring I’ve predicted. A tiny step, to be sure, but it’s a start.

Are today’s stock valuations justified in that environment? In many cases, no. This is very much a rifle shot, stock picker’s market. Index buyers should be wary. I agree with Jeremy Grantham that the last year reduced the pressure, but I think it will be back.

Timing is hard. If you pin me down, I’d probably say 2023 will have a lot of volatility. We’ll muddle through for another year. The real fireworks have not yet begun.

The thing with fireworks? When you see the fuse burning, you probably want to cover your eyes and back off. Maybe it’s a long fuse and you have some time. But you’d best be very sure about that.

Cold Weather, Travel, and SIC

I technically know that living in a warm climate doesn't really make your blood thinner. Living in Texas for 70 years I was used to wide variations in weather. The temperature here in Puerto Rico stays roughly between 70 and 90 °F for the vast majority of the time. When I travel to winter weather, it just seems colder than it used to. Shane and I intend to do a lot more traveling starting in March. I need to be in Austin, Dallas, New York for sure, and a few places in Florida. I'm sure the new fund will require more travel as well. I just hope I can put it off until the weather is “normal.”

Planning for the Strategic Investment Conference is in full swing with the entire team at Mauldin Economics. This year will be our best-ever lineup. It will be over 5 days (plus a bonus day) May 1, 3, 5, 8, 10, and 12. Get your calendar set. You can watch it live or at your leisure and of course there will be transcripts.

We got lots of great suggestions and intros but I have still not gotten that connection I want with Matt Taibbi. I think the work he is doing is important to our country and culture. While we are clearly not on the same side of the political spectrum, we are both believers in freedom of speech and truth in media. His Substack is part of my personal reading.

And with that I will hit the send button. You have a great week. If you are actually trading this market (I’m not although I do have designated traders) then stay nimble. Don't forget to follow me on Twitter.

Your enjoying the PR lifestyle analyst,

John Mauldin