by Carl Tannenbaum, Chief Economist, Northern Trust

Academic work on banking crises served as a guide for dealing with them.

Each year, we try to offer a brief note on the Nobel Prize in Economics. Composing that essay is not always easy; the work being honored is sometimes esoteric.

Such is not the case this year. Ben Bernanke, Douglas Diamond and Philip Dybvig were recognized by the Nobel Committee for their studies of banking crises. Their conclusions―that financial failures accelerate and accentuate economic distress―informed the global response to the 2008 crisis.

It stands to reason that banks will perform poorly during downturns. But the influence works in both directions: struggling banks pull back on lending, and failing banks add to the level of distress. Credit no longer moves through the economy, valuable experience is lost and uncertainty increases.

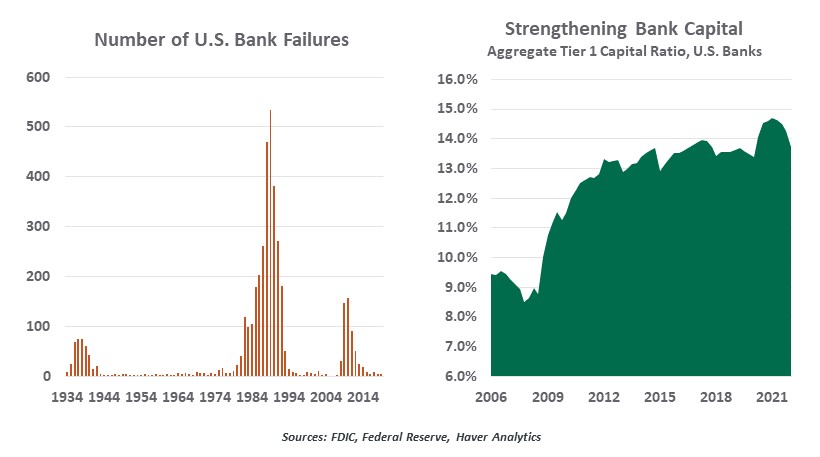

Since the Great Depression, many countries established deposit insurance systems to safeguard financial stability. And international regulators collaborated on capital requirements that (in theory) should provide a cushion during challenging times. But by 2008, changes in the financial system had moved risk to places where it was less transparent. And many banks employed strategies that spread their capital very thinly.

Academic work on banking crises served as a guide for dealing with them.

When the crisis came, all of this spilled out into the open. Fortunately, central banks had a playbook for dealing with the circumstances, founded in the research done by Bernanke, Diamond and Dybvig. Under Bernanke’s leadership of the Federal Reserve, quantitative easing was initiated, special lending facilities were established and deposit insurance was broadened. Those steps almost certainly kept us out of a second Great Depression.

Some in the public never forgave Ben Bernanke for providing assistance to the banks, whose behavior created the crisis. But had the banks been allowed to fail wholesale, it would have been a horrific outcome for everyone.

To shore up the system and prevent bank problems from spilling over to the general public, the Federal Reserve initiated annual stress tests in 2009. I was part of the group that worked with Ben Bernanke to design the tests, and feeling some small connection to this year’s prize is very gratifying. The additional capital maintained by banks placed them in good position to weather the pandemic recession, and is one reason why we don’t expect a deep recession next year.

Failure is often a valuable educational experience. It certainly proved so for this year’s Nobel Prize recipients.

Information is not intended to be and should not be construed as an offer, solicitation or recommendation with respect to any transaction and should not be treated as legal advice, investment advice or tax advice. Under no circumstances should you rely upon this information as a substitute for obtaining specific legal or tax advice from your own professional legal or tax advisors. Information is subject to change based on market or other conditions and is not intended to influence your investment decisions.

© 2022 Northern Trust Corporation. Head Office: 50 South La Salle Street, Chicago, Illinois 60603 U.S.A. Incorporated with limited liability in the U.S. Products and services provided by subsidiaries of Northern Trust Corporation may vary in different markets and are offered in accordance with local regulation. For legal and regulatory information about individual market offices, visit northerntrust.com/terms-and-conditions.

Carl R. Tannenbaum

Carl R. Tannenbaum

Executive Vice President and Chief Economist

Carl Tannenbaum is the Chief Economist for Northern Trust. In this role, he briefs clients and colleagues on the economy and business conditions, prepares the bank's official economic outlook and participates in forecast surveys. He is a member of Northern Trust's investment policy committee, its capital committee, and its asset/liability management committee.

Copyright © Northern Trust