by John Mauldin, Mauldin Economics, Thoughts from The Frontline

The Cascade Begins

High Correlation

Inflation Creates Massive Pension Problems

Broken Promises

Cleveland, Houston, Dallas, Denver, and Tulsa

Sandpiles can be fun. Nothing beats taking kids to the beach (or being a kid!) and watching their creativity blossom into all kinds of magical shapes. The problem with sand construction is it doesn’t last. I have it on good authority that building your house on the sand probably won’t end well.

The same holds for financial sandpiles. I described in a 2006 letter (and rerun many times since then) scientists using computer-simulated sandpiles to study complex systems. The piles can grow quite large and then suddenly collapse with a single added grain of sand.

The point at which this happens is unpredictable. That it will happen is highly predictable. From that 2006 letter…

“So, we end up in a critical state of what Paul McCulley calls a ‘stable disequilibrium.’ We have players all over the world tied inextricably together in a vast dance through equities, debt, derivatives, trade, globalization, international business, and finance. Each player works hard to maximize their personal outcome and reduce their exposure to fingers of instability.

“But the longer the game runs, says Minsky, the more likely it is to end in a violent avalanche, as the fingers of instability have more time to build, and, eventually, the state of stable disequilibrium goes critical.”

The stable disequilibrium of that time did, in fact, go critical a couple of years later. The sandpile collapsed but reconstruction (with ample stimulus) began almost immediately. Now we have a new and even bigger sandpile.

As noted, timing the collapse is impossible. Sandpiles, both in reality and in theory, can continue to grow much longer than we think they should. And Minsky tells us the longer it goes, the greater the subsequent collapse. But the instability is now growing more obvious. And this time, something we all depend on is in the sandpile’s shadow: our pensions. That includes individual retirement savings, which is part of how we expect to survive if not hopefully thrive as we get older. This coming Minsky moment threatens it all.

The Cascade Begins

In an August 2021 letter I quoted the original sandpile article, adding a new afterword section talking about the many new sandpiles central banks were generating. I said…

“Which particular sandpile will fall first? It could be many, but it will likely be debt-oriented. And the fingers of instability tell us that it doesn’t matter which grain of sand is the trigger, just that there will be one. Millions of investors think they can continue acting as if today will just be like yesterday, which will be like tomorrow, and then be able to sell when trouble appears.

“They’re partly right. They will be able to sell… but well below the prices they expect.

“I think the mother of all Minsky moments is building. It will not be an instant sandpile collapse but instead, take years because we have $500 trillion of [total global public] debt to work through. Remember, that debt just can’t be swept away. It is both money somebody owes and an asset on somebody else’s balance sheet. If you are retired, your pension and healthcare benefits are part of your net worth. They are assets on your balance sheet that you count on to cover future spending. We can’t just take that away without huge consequences to culture and society.

“But the fingers of instability, the total credit system, are seemingly growing with more red sand dots every month. All are inextricably linked. One day, another Thailand or Russia or something else (it makes no difference which) will start a cascade.”

That was just over a year ago. Now it appears the cascade may be beginning, with the UK pension system as another grain of red sand.

We don’t typically think of pension funds as debt but that’s what they are. The plans “borrow” worker and sponsor contributions and “repay” years later as retirement benefits. That’s their contractual obligation. But in between, they have a lot of freedom to invest the money however they think best.

Pension funds have an enormous responsibility. They actually receive only a fraction of what they eventually pay out. If returns aren’t sufficient they may not be able to pay benefits as committed without additional contributions by plan sponsors, who are often state and local governments already under massive budget pressure.

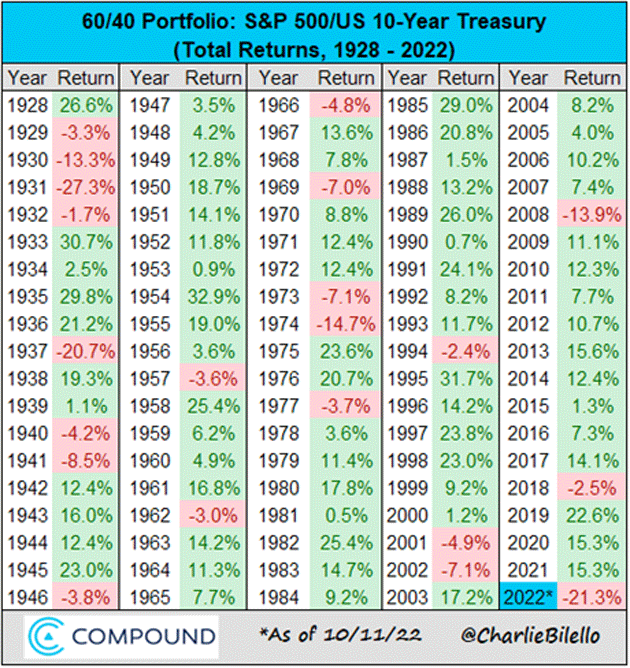

We are in unprecedented times. A 60/40 portfolio of stocks and bonds is supposed to offset volatility in equity bear markets. Bonds usually gained value in past bear markets and recessions. This time stocks and bonds are both losing money. That give us (to date) the second worst year on record for 60/40 portfolios, which is typically how pension funds are allocated.

To date, these “balanced” portfolios are down 21.3% this year, meaning they need a 27% return to get back to even. It’s even worse than that, because almost all pension funds have an inflation factor to keep up with. (more below)

Source: Charlie Bilello

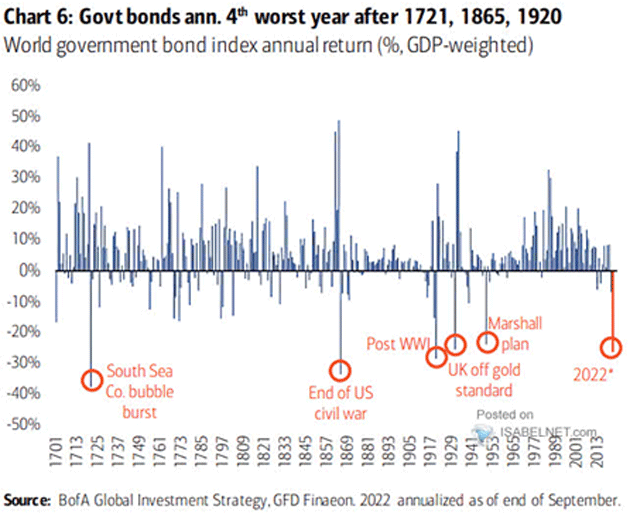

Bonds are having one of their worst years ever as the Fed raises rates from the zero bound. Remember, as interest rates go up, bonds lose value. Thankfully this doesn’t happen often, at least while stocks are collapsing as well.

Pension obligations, i.e. debt, are a significant part of the large and growing global debt load. They are big enough to have systemic effects all their own. This seems to be happening in the UK. If you want the details, I highly recommend Ben Hunt’s analysis. It is long so I won’t reproduce it here, but well worth your time to read. Seriously, this is Ben at his best!

Ben methodically explains how years of falling interest rates raised pension liabilities—a big problem for plan sponsors and managers. Lower interest rates reduced the return on the bond portion of a pension fund. In a world of zero and negative interest rates, pension funds simply couldn’t make their target returns (typically 7% and sometimes more) when 40%+ of the portfolio was making 2‒3% (at best!).

Consultants then pushed them toward something called “Liability-Driven Investment” or LDI, basically a leveraged hedge fund strategy betting interest rates would keep dropping. They showed data that for the last 30 years the trade ALWAYS won. Except the last 30 years was a period of falling rates and inflation, which everyone assumed would continue. It worked well until rates went higher… or, as Ben says, “until the math broke.” Now they all want to exit at once.

In effect, UK pensions are in a solvency crisis. Giant debtors are in danger of not being able to meet their obligations—not the pension benefits years from now, but margin calls due immediately. They are thus frantically trying to raise liquidity. Their combined efforts to sell UK government bonds all at once raised rates even further, aggravating the problem and creating new ones. The word “cascade” is quite accurate. Each step leads to another one, bigger than the last. As of this morning, it looks like the Bank of England is calming the market, but it serves to demonstrate how fragile the debt/leverage system is. We will know more next week.

I have sat in numerous pension board meetings, mostly as a guest speaker invited by a member of the pension board. I make my presentation and then listen to consultants tell them essentially the exact opposite. Growing your portfolio at (x%) is easy if you just stick to this model portfolio we have designed (for hefty fees). They smoothed those average yields over time so that target rates could be achieved. Until a crisis…

Very simplistically, the UK pension crisis uses math akin to that used by Long Term Capital Management’s Nobel laureates, which showed that based on history these bonds always moved in the direction of becoming the same valuation as other bonds. Thirty-year bonds would assume characteristics of 29-year bonds, generating a slight profit. So, the logical conclusion was to leverage up to 30 times on these safe instruments to get a good target return. Then diversify into the bond markets of scores of nations, as the trades are similar.

Except the math broke. Traders began to notice and started to front run LTCM, causing the trade to yield less and then “inexplicably” the trade dynamic reversed and hedge funds piled on, causing LTCM to lose $4 billion or so leveraged 30 times. This almost broke the financial markets in 1998.

There is never just one cockroach. We will see more of these “investment programs” fail to achieve the desired results, forcing pension boards to request more principle from their sponsors.

US pensions use different hedging tools, so they don’t have the particular problem UK funds are enduring. But they’re still not in great shape.

High Correlation

The large pools we call “pension funds” fall mostly in the defined benefit category. Money from a company’s workers, for instance, goes into a giant fund that promises to pay them a defined amount from retirement until death. Lifespans being uncertain, this is an inherently risky structure for the sponsor. That’s why US private employers have mostly abandoned it. But defined benefit plans are still common for state and local governments and public employee unions.

The pension math Ben Hunt describes works the same here. Falling interest rates and rising inflation increase the present amount needed to meet future obligations. The difference between US and UK plans is that US plans can buy government bonds in their home currency, which is also the global reserve currency, and is the world’s deepest and most liquid financial market. They don’t need they kind of derivatives that are exploding in London.

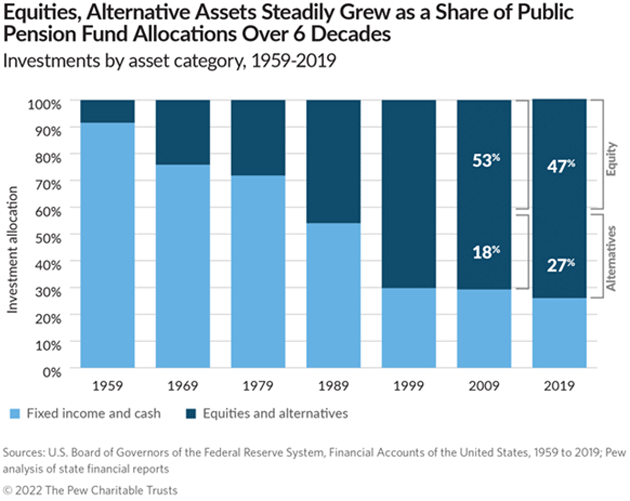

The bigger problem for US plans is low fixed income rates led them to fill their portfolios with riskier assets like stocks, real estate, venture capital, and assorted “alternative” investments.

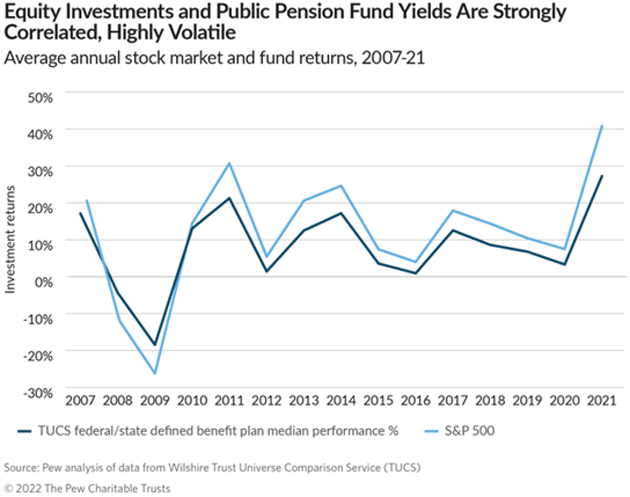

This is good if those investments succeed but the odds they will do so decline as more plans throw more money into them. This chart shows the correlation between defined benefit plans and the S&P 500.

So, if pension plan returns are a) highly correlated to the S&P 500 and b) highly correlated to each other, what do you think will happen when the S&P 500 has an extended bear market? And by that, I mean not a bad year or two, but an extended 1970s-style generational sell-off. We are long overdue for one.

I’ll answer my own question: Plans will all change course at once, stampeding like buffalo to whatever they consider safer ground. And not caring who they run down in the process.

This wouldn’t necessarily prevent plans from paying benefits. Most keep enough cash or near-cash assets on hand to ride out a short downturn. But it’s quite likely at least a few plans would fail, and that will generate doubt and fear among retirees… who will, in all likelihood, have seen their other assets plummet in value, too.

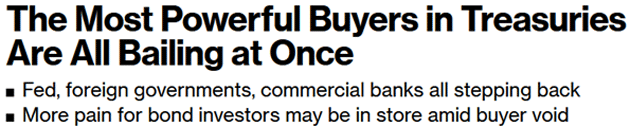

At that point the pressure for bailouts and government interventions will grow. But it isn’t clear that will even be possible. Who would buy all the new Treasury debt? Here’s a Bloomberg headline from last week.

Here’s how that article opens.

“Everywhere you turn, the biggest players in the $23.7 trillion US Treasuries market are in retreat.

“From Japanese pensions and life insurers to foreign governments and US commercial banks, where once they were lining up to get their hands on US government debt, most have now stepped away. And then there’s the Federal Reserve, which a few weeks ago upped the pace that it plans to offload Treasuries from its balance sheet to $60 billion a month.

“If one or two of these usually steadfast sources of demand were bailing, the impact, while noticeable, would likely be little cause for alarm. But for every one of them to pull back is an undeniable source of concern, especially coming on the heels of the unprecedented volatility, deteriorating liquidity and weak auctions of recent months.

“The upshot, according to market watchers, is that even with Treasuries tumbling the most since at least the early 1970s this year, more pain may be in store until new, consistent sources of demand emerge. It’s also bad news for US taxpayers, who will ultimately have to foot the bill for higher borrowing costs.”

I talk often about the way years of policy mistakes leave nothing but bad options. This is where it led. Easy money sparked inflation which the Fed is (appropriately, in my view) trying to squelch with tighter policy. But that’s raising the Treasury’s borrowing costs and—maybe more to the point—strengthening the US dollar, which globalizes our problem.

We have grown accustomed to fiscal and monetary rescues in every crisis: 2000, 2008, 2020. That may not be an option next time. Then what?

But wait, there’s more.

Inflation Creates Massive Pension Problems

Many pension funds have an inflation adjustment, typically using some version of CPI. The Social Security Administration informed us this week that Social Security cost-of-living adjustment will be 8.7% in 2023, the highest increase in 40 years and coming on top of 5.9% last year! Here is how my SS payments look. First, remember that I paid in the max amount for almost 40 years. And I waited to 70 to start getting my payments. My old payment was $4,130 (after last year’s increase). Now it will rise to $4,489. Almost $54,000 a year. Multiply that by total SS payments?

What was $1,194,842 trillion rose to $1,285,640 trillion. A $91 billion increase. In one year! This does not include military or other government pensions, presumably all of which will rise by almost 9%. (Should I even mention Medicare costs?) All of these entitlements rise inexorably faster than revenues as we are now at the point where the government will start to have to pay 4%-plus for its $31 trillion debt, well over $1 trillion in interest alone in a few years.

This is going to create a future crisis in the US which will, along with other policy problems, produce a crisis that makes the UK pension problems small potatoes. Coming to a theater near you in the not-too-distant future.

Broken Promises

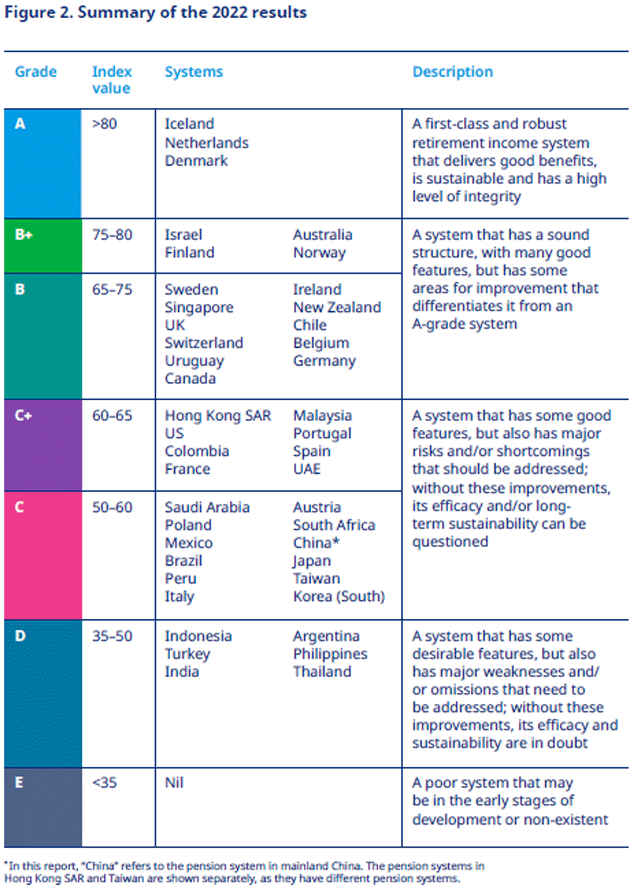

Last week I ran across the Mercer/CFA Institute’s newest “Global Pension Index” report. They look at pension systems by country and rate them for adequacy, sustainability, and integrity. Such comparisons are difficult because pension systems and practices vary so widely, both among countries and within them. But it’s a fair attempt to compare everyone against a standardized benchmark. Here’s the results summary.

Source: Mercer CFA Institute Global Pension Survey

Congratulations, workers and retirees of Iceland, Netherlands, and Denmark. Your systems are “first-class and robust.” They’re also relatively small.

Look a bit lower at the “B” graded category for some larger economies. There we see the UK—which based on recent events probably should be lower—along with Switzerland, Canada, and Germany.

The US and France get a C+, meaning “major risks and/or shortcomings.” Going even lower, we see some very large economies in the C and D categories: Mexico, Brazil, Italy, China, Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, Turkey, India, Argentina.

“Efficacy and sustainability are in doubt” is a very kind way of saying, “You folks are in trouble.” The US has serious problems, but we also have serious capabilities. We can muddle through almost anything. I am not sure that’s the case in some of these other countries.

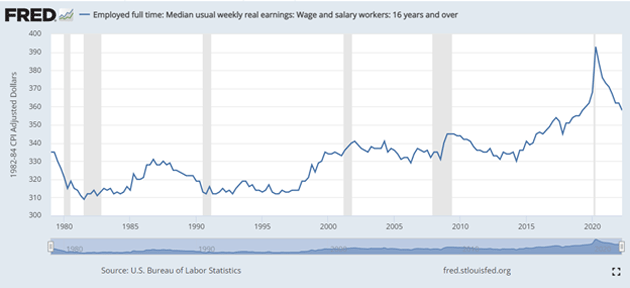

Workers are barely keeping up. As Ben Hunt wrote:

“Over the past 43 years, real wages for Americans are up 6.9%. Not 6.9% per year. 6.9% total for forty-three years.”

That’s roughly 0.16% a year. Hard to get ahead on that. This is why I am so fixated on inflation and have been since it was clear we were going to have a real problem. It totally screws with the average worker.

Jerome Powell appears to have a similar fixation. Will he maintain it until he drives a stake through the heart of the inflation vampire? Will Powell transform into vampire slayer Van Helsing?

Yes, I realize this will cost jobs. I have been pounding the table seemingly forever about policy and bad choices. We now have only bad choices. We can disagree (politely, please) about priorities, but as I look at economic history, inflation is the worst of multiple evils.

In that 2021 sandpile update, I wrapped up with this:

“Economic sandpiles that have many small avalanches never have large fingers of instability and massive avalanches. The more small, economically unpleasant events you allow, the fewer large and, eventually, massive fingers of instability will build up.

“Efforts by regulators and central bankers to prevent small losses actually create the large fingers of instability that bring down whole systems and spark global recessions. And, increasingly, the unfunded liability of government promises will be the most massively unstable finger.

“In that crisis, things that should be totally unrelated will suddenly become intertwined. The correlations of formerly unrelated asset classes will all go to one at the absolute worst time. Panic and losses will follow. Governments will try to stem the tide, perhaps appropriately so, but, eventually, the markets have to clear.

“There is a surprising but critically powerful thought in that computer model from 35 years ago: We cannot accurately predict when the avalanche will happen. You can miss out on all sorts of opportunities because you see lots of fingers of instability and ignore the base of stability. And then you can lose it all at once because you ignored the fingers of instability.”

I know many, perhaps most of my readers are fortunate enough not to depend on someone else’s pension promises. But you do depend on someone’s promises. Every non-tangible asset—not to mention every currency—represents some kind of promise. Usually, the promises are good. Not always.

Your investments, pension or otherwise, are vulnerable to those fingers of instability. You need to protect yourself from the sandpile’s collapse while also participating until it happens.

Easy? No, not at all. But necessary if you want to survive the avalanche.

Cleveland, Houston, Dallas, Denver, and Tulsa

Shane and I will be going to Cleveland Monday for four nights and “fun-filled” days with Dr. Mike Roizen at the Cleveland Clinic. Another colonoscopy and endoscopy for me, seeing lots of other doctors for basic checkups. Normally it is just a few days, but both of us are getting “invasive” procedures that require more time. For me, that is the price of aging. Not sure how I will get a letter written next week, but we will see.

Then the end of the next week we go to my 50th reunion at Rice University, where I will be lucky enough to get invited to a private presentation by Nobel Laureate Thomas Sargent talking on inflation. I will take notes. I will be in Dallas November 16, speak at a CFA dinner in Denver with my friend Vitaly Katsenelson, then back to Dallas for a few days before going to Tulsa to be with family for Thanksgiving.

I am busy working on what will be a series of white papers on energy. The research material is vast and the subject is complex and controversial. But it is a lot of fun to explore. And with that I will hit the send button. Don’t forget to follow me on Twitter. And tell your friends and your followers on Twitter to follow me as well. I/we have a lot of fun. Have a great week.

Your not really excited about medical “procedures” analyst,