by Vaibhav Tandon, Senior Economist, Northern Trust

A more integrated global economy is making sanctions less effective.

A nation that is boycotted is a nation that is in sight of surrender. Apply this economic, peaceful, silent, deadly remedy and there will be no need for force. It does not cost a life outside the nation boycotted, but it brings a pressure upon the nation which, in my judgment, no modern nation could resist.” - U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, 1919.

President Wilson was an early proponent of sanctions as an alternative to war, and he was ahead of his time. In recent decades, sanctions have become a vital tool of governments’ foreign policy. The idea behind sanctions is to restrict trade and financial flows towards or from the target nation to punish an unsolicited action or coerce compliance with some policy goals.

Unfortunately, the outcomes have often been different from what the former president envisioned. History shows that sanctions don’t work reliably and have rarely produced desired results. In the runup to World War II, boycotts and bans against Germany by the allied forces and against Italy by the League of Nations didn’t bring about their collapse. More recently, the vigorously imposed sanctions against Iraq since the 1990s delivered only limited outcomes; over 2,000 accumulated sanctions on North Korea neither impacted its trade with China, its largest trading partner, nor led to de-nuclearization.

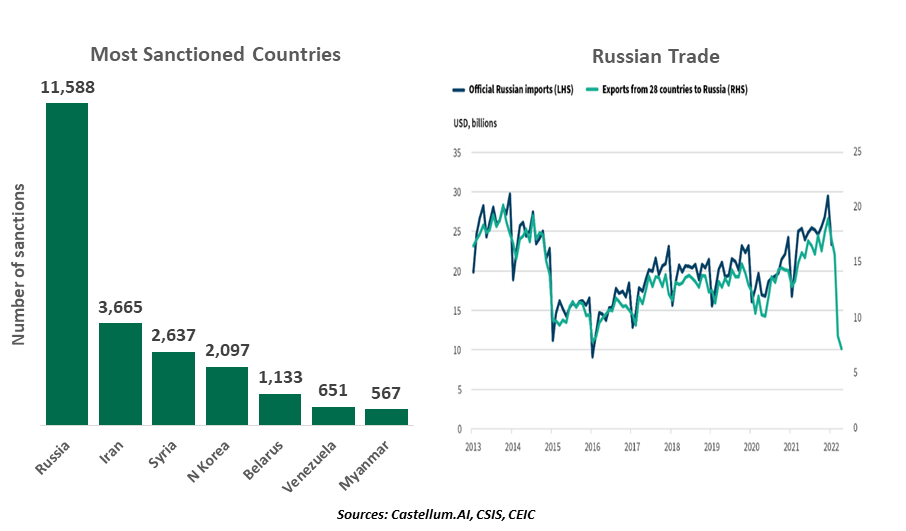

Therefore, the effectiveness of new economic sanctions on Russia is rightly facing scrutiny. Several Russian agencies, companies and individuals close to President Putin were already facing sanctions since its annexation of Crimea in 2014. The U.S. and its allies upped the ante by imposing further punitive measures on Moscow, immediately following its invasion of Ukraine. Today, Russia is the world’s most sanctioned country.

Sanctions can cause great economic pain, and this time is no different. Western sanctions are imposing far-reaching consequences upon the Russian economy. Since April, the country’s import flows have been cut in half. Moscow is highly dependent on imported electrical and electronic equipment, with several European and American firms acting as key suppliers of these products. As a result, activity in industries like pharmaceuticals and auto manufacturing has taken a major hit from disruptions in supplies of components. The ruble tumbled in the weeks after the invasion, causing the central bank to impose capital controls and raise interest rates. As well as sanctions, several Russian banks have been removed from the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT) platform, in a bid to isolate Moscow from the global financial system.

Even back in the 1930s, Italy under Mussolini experienced substantial economic hardship from an embargo on arms and metals. Industrial production and exports plummeted, with prices of all commodities hitting the roof.

Western sanctions are taking a heavy toll on the Russian economy.

But sanctions can be a double-edged sword, leading to unwanted economic consequences, including for sanctioning nations. This is the first time in almost a century that a country as big as Russia has been subjected to far-reaching punitive measures. The implications were bound to be have wide-ranging ripple effects.

Russia is the world’s 11th largest economy, a major exporter of oil, gas, grain and industrial commodities. As a result, sanctions both disrupted supplies and contributed to a commodity price surge. Prices of products like oil are set on a global basis, spreading the pain of sanctions to nations not remotely connected to the fight.

Closer to the conflict, while Europe initially threatened to ban Russian energy purchases, Moscow has retaliated by cutting crucial gas supplies to the continent. Europe, especially Germany, is heavily dependent on Russian energy. Hence, finding alternate sources of supplies will be difficult and costly.

Firms and labor pay a heavy price when commercial relations between countries are disrupted. Global corporations have lost $59 billion from Russian sanctions, which forced them to cut business operations in the country. Empirical research shows that economic sanctions between 1970 and 2000 banned up to $19 billion annually in potential exports from the U.S., equivalent to around 200,000 jobs.

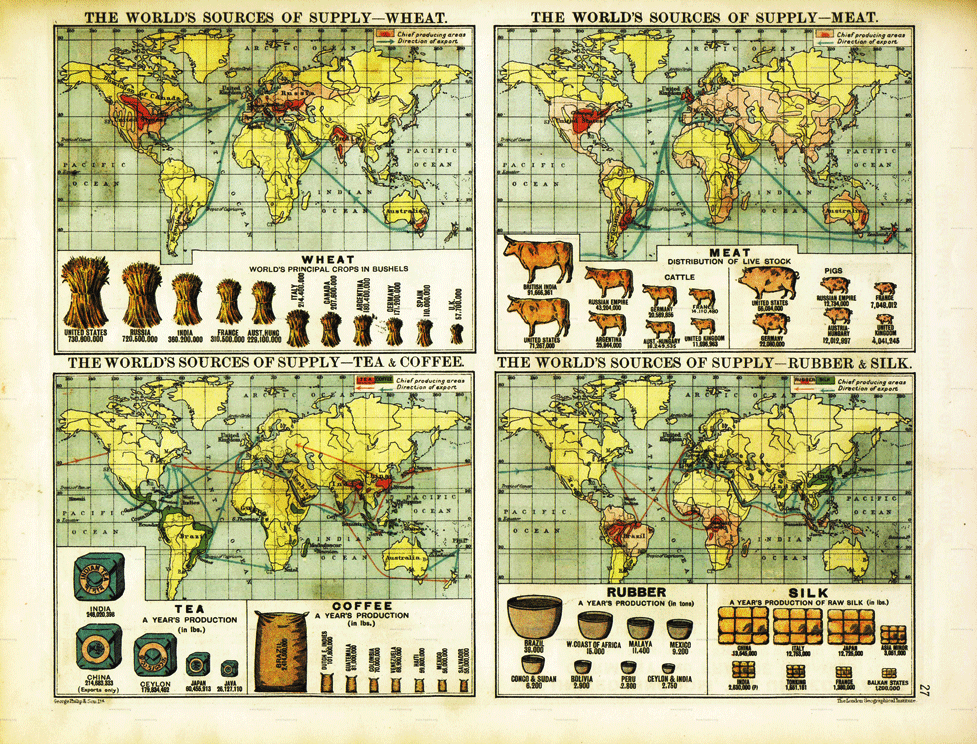

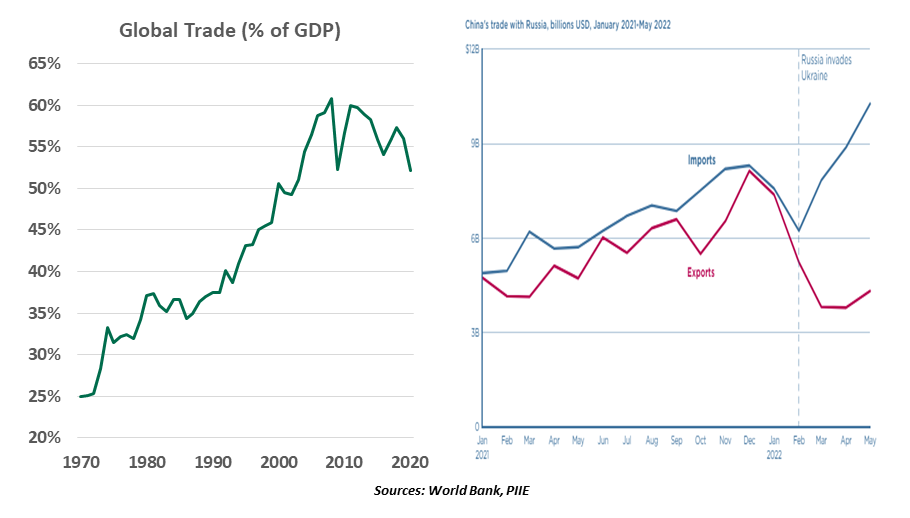

The global economy is far more integrated today than it was a century ago, with the share of world trade much higher. The availability of alternative trade routes allows circumvention and contributes to the failure of sanctions to meet their stated objectives.

Unilateral American sanctions had achieved foreign policy goals in only 13% of the cases where they have been forced in the three decades to 2000. Back in the 1900s, the measures by the League of Nations failed to halt Rome’s invasion of Ethiopia, as Italy continued to import commodities like coal and oil needed to keep its economy running.

Even today, while Moscow is struggling to import goods, export sanctions are falling short of delivering their desired ends. Energy consumers like China and India have emerged as major alternate demand centers for Russian supplies. Coupled with higher energy prices, Russian exporters are posting record earnings, with the current account surplus reaching $110.3 billion in the first five months, a three-fold increase over the same period in 2021. Similarly, while removal from the SWIFT platform raised the costs on Russia, an increasing number of countries are settling trade in rubles, bypassing financial sanctions.

Globalization has made sanctions less effective.

Trade limitations can also spur development and make economies more autonomous in the long run. The U.S. administration’s restrictions on sales of American technology to Chinese corporations has only spurred Beijing’s chipmaking industry. Now, in order to reduce exposure to the U.S. financial system, Beijing is also making efforts to reduce its reliance on the dollar by making the renminbi more appealing in international finance.

Globalization has increased the economic costs of using sanctions against large economies and also made them easy to circumvent. The more they are used, the less effective they become. However, if diplomacy fails, sanctions should be considered the penultimate option. Despite its flaws, an economic war is a preferable alternative to an armed conflict.

Information is not intended to be and should not be construed as an offer, solicitation or recommendation with respect to any transaction and should not be treated as legal advice, investment advice or tax advice. Under no circumstances should you rely upon this information as a substitute for obtaining specific legal or tax advice from your own professional legal or tax advisors. Information is subject to change based on market or other conditions and is not intended to influence your investment decisions.

© 2022 Northern Trust Corporation. Head Office: 50 South La Salle Street, Chicago, Illinois 60603 U.S.A. Incorporated with limited liability in the U.S. Products and services provided by subsidiaries of Northern Trust Corporation may vary in different markets and are offered in accordance with local regulation. For legal and regulatory information about individual market offices, visit northerntrust.com/terms-and-conditions.