by Jeffrey Kleintop, CFA®, Managing Director, Chief Global Investment Strategist, & Michelle Gibley, Charles Schwab & Co., Inc.

Stocks, bonds, and cash are all in a bear market or teetering on the edge of one—a very rare event. Over the past 72 years, there have only two prior periods with a triple bear.

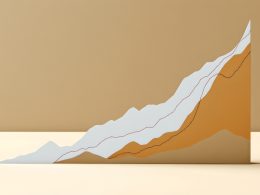

The three bears

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg data as of 5/20/2022.

Stock market represented on log scale indexed to 100 on Dec 31, 1969. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

- On Friday, the S&P 500 and MSCI World Index both briefly slipped into bear market territory before recovering by the end of the day, closing very near the -20% threshold from the market peak on January 4, 2022.

- U.S. bond yields have jumped in 2022, posting their worst start to a year on record. Other bond markets around the world have also performed poorly. The trend in German bond yields reflects the U.S., trending lower since the early 1980s until recently. Both the U.S. and German 10-year bonds have suffered a loss of just under 10% on a total return basis so far this year.

- The return on cash, represented by three-month U.S. Treasury bills, has been lagging inflation, resulting in a negative return on an inflation-adjusted (or real) basis for many years. The surge in inflation over the past year has pushed the real return deep into negative territory, similar to where it was very briefly in both 1951 and 1980.

Will a bull market return?

- Occurrences of cash bear market extremes historically marked a peak in inflation. We may already be seeing signs that inflation peaked last month, such as falling input prices and excess inventories reported last week at big box retailers like Target, Kohls, and Walmart (which we had projected in the November 2021 article Will Shortages Lead To Gluts?)

- Emergence of climbing global bond yields since 1980 have been consistently followed by some deflationary event that contained the rise: 1986 oil crash, 1989 fall of USSR, 1991 Japan going bust, 1998 Asian contagion, 2001 China joining the World Trade Organization, 2008 housing bust, 2011 Eurozone debt crisis, 2013 shale revolution, 2020 global pandemic. Perhaps another deflationary event may be just around the corner as risks of recession rise.

- Once stocks breached the 20% threshold, the time it took to reach their bottom before beginning a new bull market was often surprisingly short: 39 days in 1966; six days in 1987; 36 days in 1990; the same day in 1998; 12 days in 2011; the same day in 2018; and 11 days in 2020. The four exceptions to these brief periods were: the start of the 1970s when it took 117 days; the end of the inflation era in the early 1980s when it took 157 days; the early 2000s Tech Wreck where it took 595 days to bottom; and the 2008-09 Great Financial Crisis, which took 241 days.

How much lower until the bottom?

The history of analysts' estimates for the next 12 months of earnings begins in 1988, allowing us to look at nearly 35 years of the forward PE ratio. Currently, the forward PE for the MSCI EAFE Index of the stocks of international developed countries is well below its long-term average, but not yet in line with market lows associated with the prior seven recessions in Europe or Japan. On average, a recession would see the PE fall another 4%. During the two financing crises (Great Financial Crisis 2008-09 and European Debt Crisis 2011-13), forward PEs fell an additional 25-35%.

Close to pricing in a recession?

Source: Charles Schwab, FactSet and Bloomberg data as of 5/19/2022.

Shaded areas denote recessions in Europe or Japan. Price-to-earnings (PE) based on forward 12 months consensus estimates. A log or logarithmic scale is a non-linear scale used to illustrate rate of change. Past performance no guarantee of future results.

Number of companies with upward and downward revisions back to pre-war levels

Source: Charles Schwab, FactSet data as of 5/16/2022.

Goldilocks?

- Managing volatility risk - We have been recommending maintaining strategic weights across asset classes and sectors, not because we don't have any ideas, but because diversification itself is an especially good idea right now in the current period of heightened volatility, which we foresee continuing. The correlation across stock markets has fallen to among the lowest levels in 20 years, magnifying the benefits of diversification.

- Managing inflation risk - Historically, when inflation expectations are rising, international stocks tend to outperform U.S. stocks. One reason is that international markets tend to be more inflation sensitive, with more companies that benefit from higher inflation than those that suffer.

- Managing rising interest rates - Shorter duration stocks can help manage the risk of rising rates. Stocks with more immediate cash flows, rather than cash flows in the distant future, have outperformed since rates bottomed in 2020, and tend to be more dominant in international markets.

- Managing downside risk - Companies around the world announcing new or increased stock buybacks seem to be outperforming than those that don't. Over the past decade, the biggest buyers of stocks have been the companies themselves, rather than individual investors.

Michelle Gibley, CFA®, Director of International Research, and Heather O’Leary, Senior Global Investment Research Analyst, contributed to this report.