by Rick Rieder, Russell Brownback, Trevor Slaven, & Navin Saigal, Blackrock

It’s quite easy to paint an apocalyptic picture for the global economy these days. If the war in Ukraine were to escalate, skyrocketing commodity inflation could ensue; and if China were to continue to pursue a Zero Covid policy amidst rising case counts, supply chains originating in Asia could get shut down again. Paying higher prices for dwindling quantities would send stagflationary alarm bells ringing through newspaper headlines, even more than they already are. Further, if U.S. consumption were to nonetheless stay strong, despite the cost-push inflation, buoyed by savings and pent-up demand, then the Federal Reserve (Fed) may be emboldened to tighten policy beyond neutral levels, or to withdraw liquidity at a pace that would hold real economic implications. And if the Fed were to aggressively do “whatever it takes” to kill off the recent spike higher in inflation, then a negative feedback loop could form with consumption slowing and financial markets deflating (with recession fears replacing stagflation fears).

Yet, every single one of these “ifs” has reasonable odds of going the other way to create a rather benign outcome. If some sort of resolution were to be found in Ukraine, and if China were to pursue an optimization policy oriented around economic stability, then supply-driven, cost-push, inflation could be tamed more naturally. If U.S. consumption were to go from great to merely good, in sympathy with the higher prices already in the system, the Fed could take policy to neutral judiciously, as opposed to quickly, with the luxury of time to then decide whether to go further or not, depending on how economic conditions unfold. The outcome of all this? Inflation expectations would be contained, and a positive feedback loop could form with a resumption of rising real growth, resulting in financial asset prices that would respond to real economy cues (stocks and bonds would complement each other in portfolios, as they historically have, rather than compound losses).

Each permutation and combination of these “if/thens” (both ugly and benign) seems to have exerted its own gravitational pull on markets at some point this year, sometimes simultaneously, creating a great deal of uncertainty and a multi-directional backdrop for investing as dizzying and complex as an M.C. Escher staircase (see Figure 1). We think that the outcomes of the “ifs” in question are so extreme and far-reaching that perhaps an investor’s goal of capital appreciation should, for now, be balanced with that of capital preservation, until a few more data points provide some much-needed clarity on the trajectory of the global economy.

Source: https://www.digitalcommonwealth.org/search/commonwealth:3r076s67r

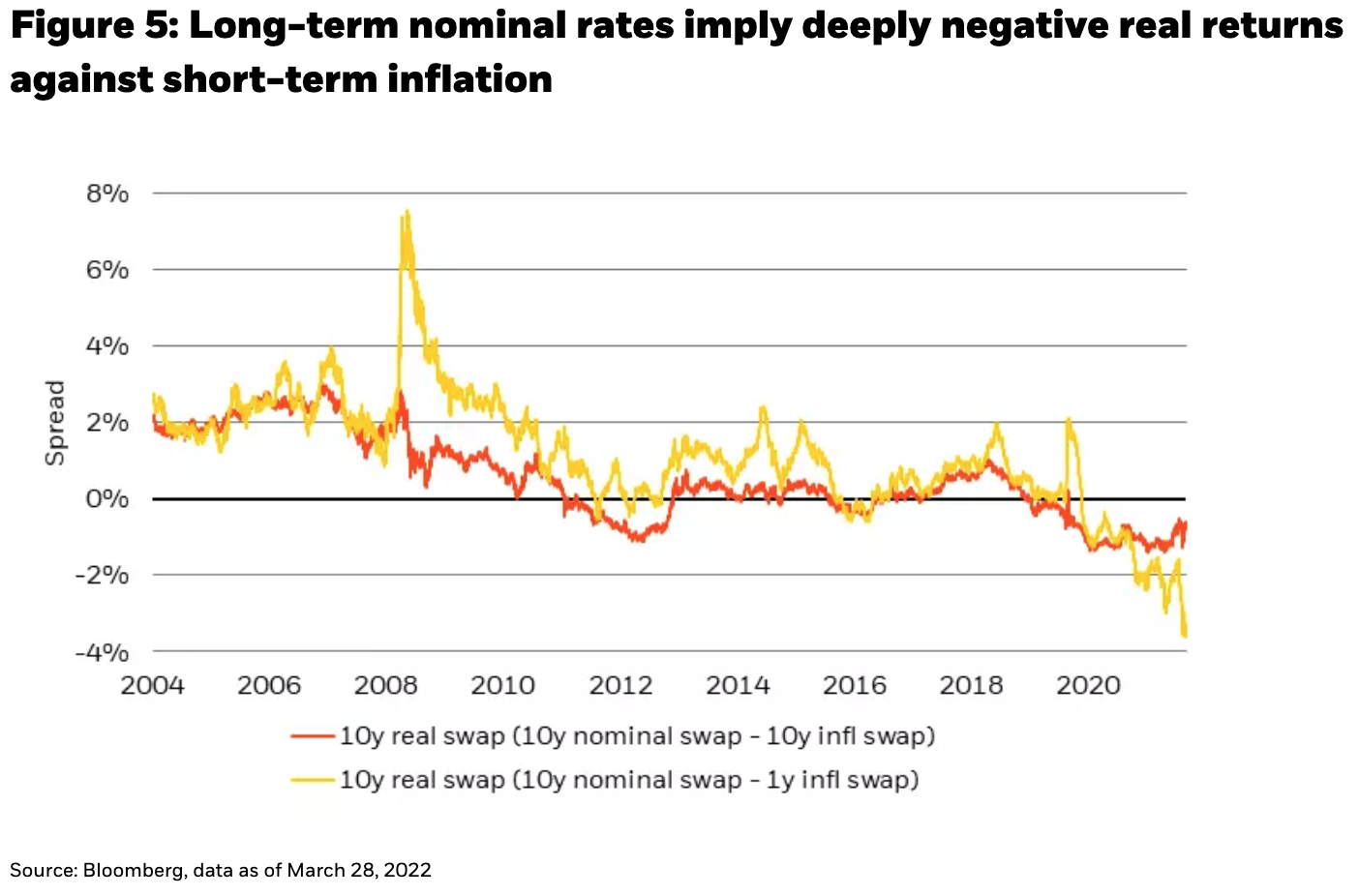

Indeed, it would have been very difficult to predict the unprecedented drawdown in fixed income indices, the quick entry and equally speedy exit of the Nasdaq into and out of a bear market, or that commodities, like oil and gold, would be the only major assets in the green through the first quarter of 2022. Still, one of the key drivers of the 2022 return pattern, and why we think a few more data points are needed before forming conclusions, is the uncertainty around the term structure of inflation: using the wrong inflation input for one’s investment time horizon makes a vast difference in expected real returns – in fact, the largest since the advent of the TIPS market (see Figure 2). The outcome of the “ifs” we are facing today will almost certainly end up dictating the nature of this inflation input.

The Russia-Ukraine War “If”

Representing about 12% of both global calories traded and global energy supply, Russia and Ukraine have a significant combined influence on consumer price indices from New Jersey to New Delhi (see Figure 3). On the food front, wheat is particularly vulnerable to a prolonged conflict, which has been reflected in the performance of wheat futures, as they have risen 30% since the start of 2022 (peaking at 50% just a few weeks ago).

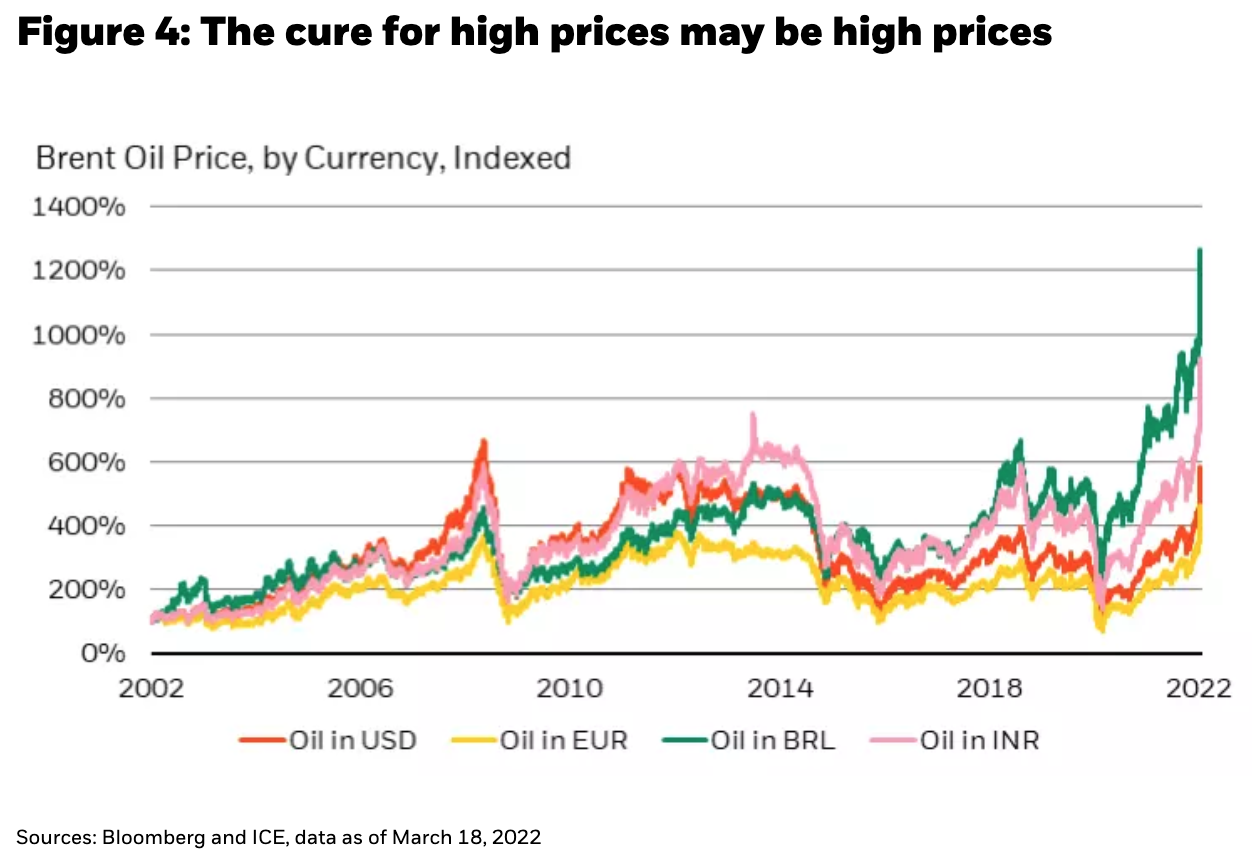

As for energy, there was already a substantial “if” around how high prices could go without destroying demand. While oil prices in developed markets are causing consternation, prices in some large emerging markets have reached nosebleed levels in recent weeks (see Figure 4). The unwillingness of companies to spend on capital expenditures (capex), having been scarred by prior episodes of overinvestment, is compounded now by uncertainty around the future of Russian supply, and may keep prices high enough, for long enough, so as to accelerate a longer-term transition to alternative sources of energy.

The cost-push inflation “If”

So, already sticky-high global inflation has been shocked higher, while persistent supply chain bottlenecks and de-globalization are threatening to become stark economic realities. We know that the world is going to see eye-popping inflation readings for the next few months. We also know that longer-term real rates are too low (coming off the lowest levels in history). However, if this near-term inflation shock were to last for a longer period of time than the market is expecting, then long-term nominal rates would have to rise significantly so as not to appear grossly mispriced (see Figure 5).

The stagflation “If”

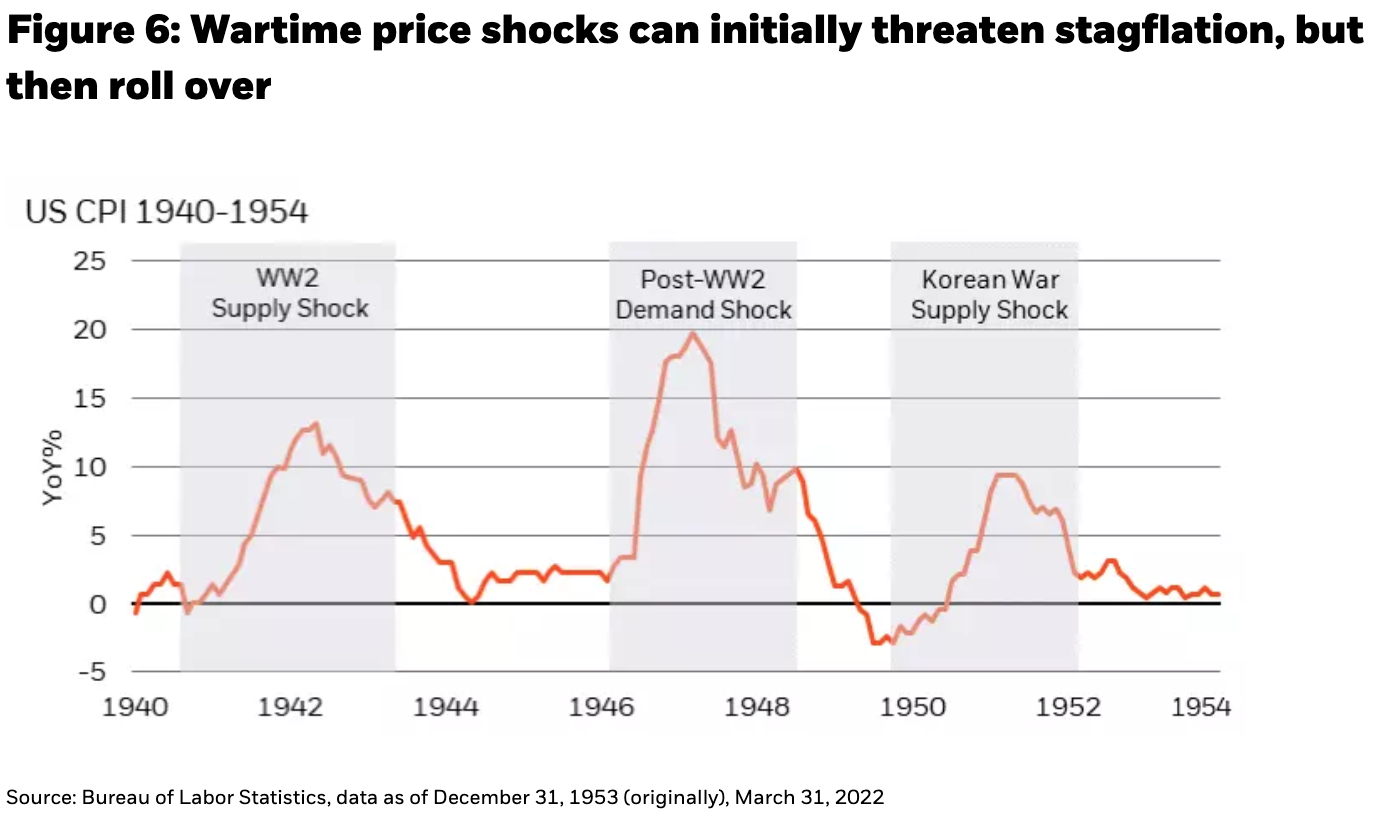

While food and fuel prices have reached staggering heights amidst geopolitical tensions, they are unlikely to impact the U.S. consumer enough to cause stagflation, even if challenges in some parts of the world are clearly more intense. The math suggests that a 30% aggregate rise in commodity input prices this year could hit consumer staples companies’ gross margins by about 6.4% - a material hit, to be sure, but not nearly a death blow. Should those companies pass on the entirety of that 6.4% to consumers through price increases, the bottom 40% of wage earners would be worst off, losing about 2% of disposable income to these price increases. That could translate into a loss of 0.7% of GDP for the U.S. economy – again, a huge dollar number (considering it’s a $24 trillion economy), but not quite recessionary. In fact, previous wartime and post-war dislocations look similar to the inflationary episode we are facing today (see Figure 6). Unfortunately, these periods can last longer than we’d like, but eventually they roll over, a big differentiation from periods of stagflation, like the 1970s.

The consumption “If”

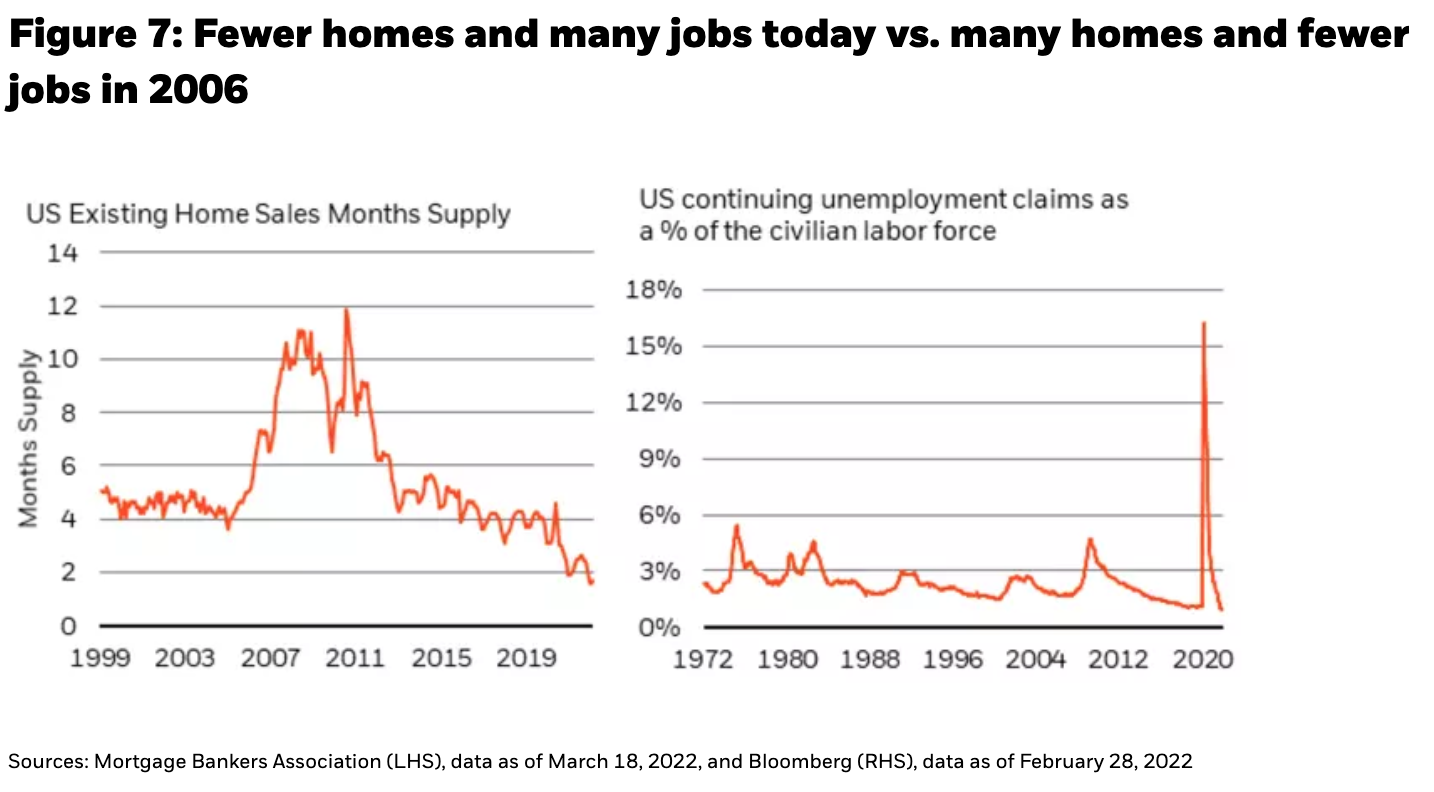

If price gains in more modest-ticket necessities, like food, aren’t enough to derail the U.S. economy, what about the biggest-ticket necessities, like houses? With significantly higher house prices being met by rising mortgage rates, the concern of less affordable housing is real. Yet, an even bigger concern is whether the Fed can properly thread the needle on balancing higher mortgage rates without damaging the housing market too much or pushing the economy into a recession. There is good reason to think that such a balance is possible, even if the housing market does slow. While a housing slowdown will invite comparisons to the mid- 2000s, today’s market is the opposite of 2006: there is no available supply of homes, especially at reasonable prices (restricting forward demand), amidst the tightest labor market since at least 1970 (meaning reasonably priced homes that do come to market are likely to be snapped up, as displayed in Figure 7).

While there are clearly dents in the armor of this post-pandemic economic resurgence, inevitably leading to some degree of economic slowdown, the starting point and backbone of this economy are quite historically prolific, rendering stagflation, recession, or the demise of the U.S. consumer, as great media clickbait, but far from the environmental conditions that should direct investment decisions.

Follow Rick Rieder on Twitter

The Fed “If”

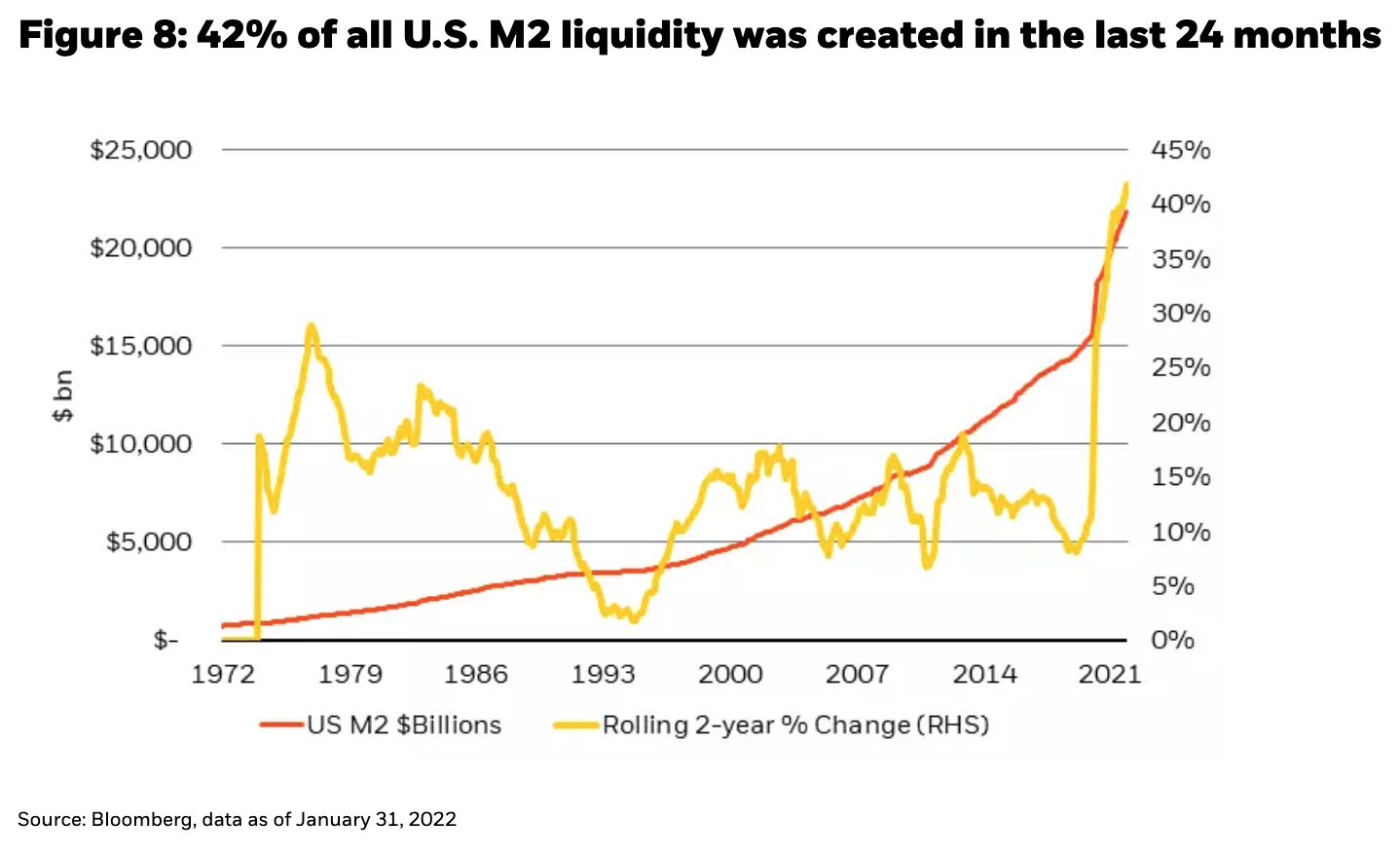

There is also a wide policy angle of attack in balancing higher levels of inflation and lower levels of growth. One of the Fed’s tools is moral suasion. Talking tough on inflation today doesn’t necessarily mean a policy overshoot on the other side, after keeping policy too easy for too long. Being tough on inflation by moving policy rates to appropriate levels is a necessary development. Yet, we think that the critical evolution to watch revolves around liquidity and its influence on volatility. While there is some truly excessive liquidity in the system at present, if too much is removed, too rapidly, it could create a systemic shock by deflating the prices of goods, services and financial assets, as quickly as it inflated them (see Figure 8).

The Europe “If”

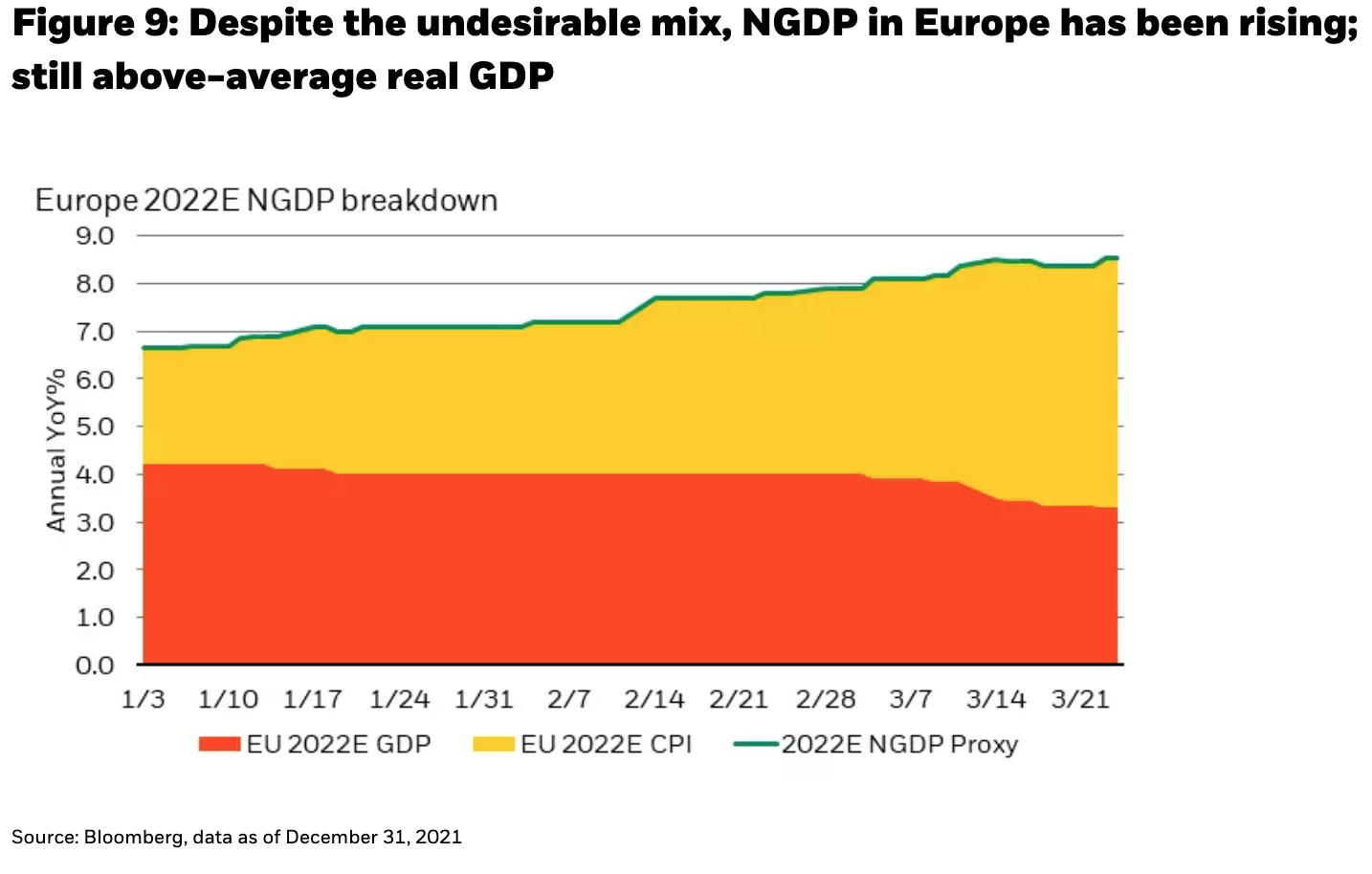

Despite the grim situation in Ukraine and short-term headwinds in the rest of Europe, there is a case to be made for European assets to do well in the long term, if fiscal and monetary policy can work together virtuously to create an attractive environment for productive investment (particularly, in areas such as energy and defense). While near-term uncertainty and concern over the European economy could very well continue to pressure the euro, monetary policy that is targeted at inflation and fiscal policy supporting energy, climate and immigration (among others) could very well ultimately buoy the currency and attract tangible investment into the region over the intermediate-to-long-term (see Figure 9).

The economic “If/Thens” lead to a series of investing “If/Thens”

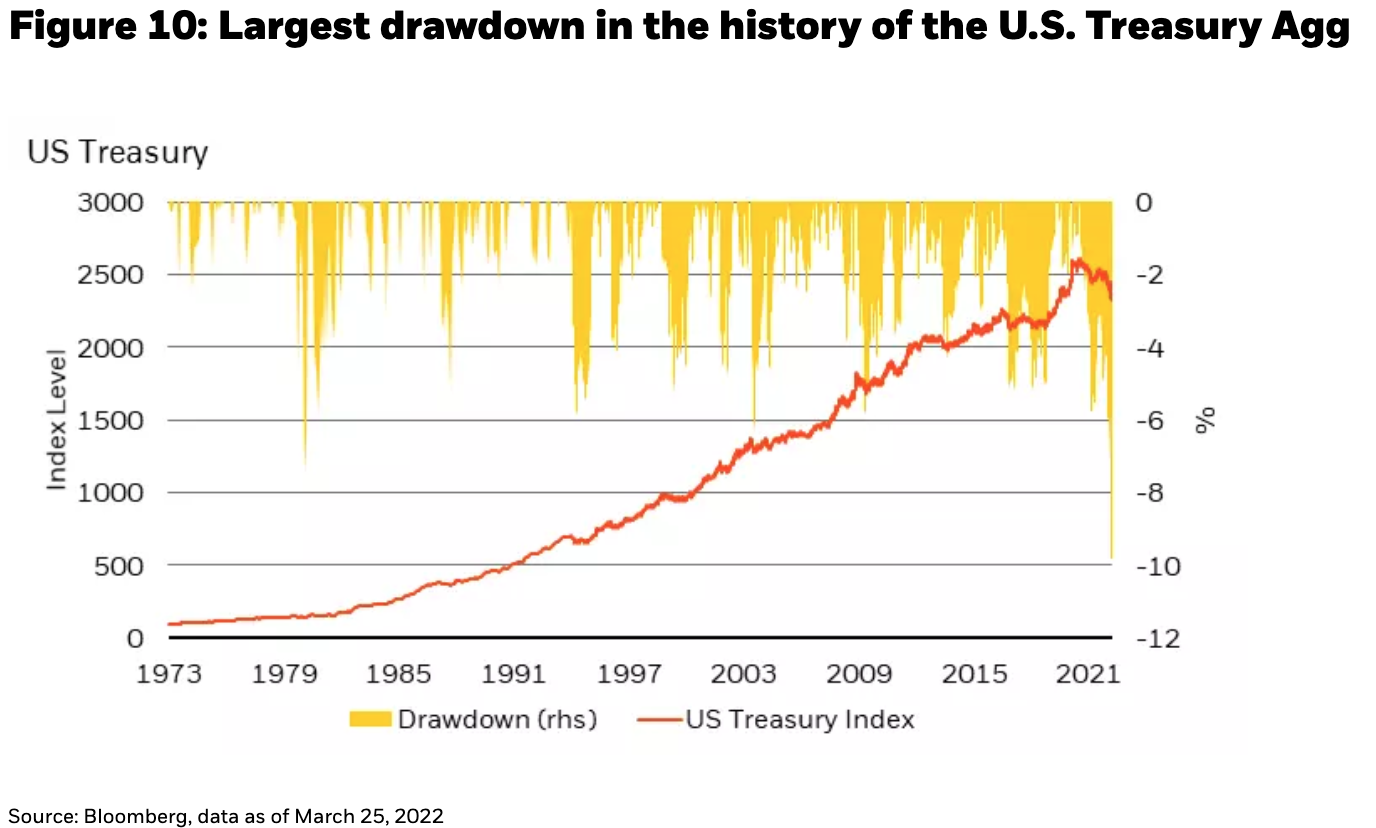

Nobody has seen the losses we’ve just been through in many high-quality fixed income indices because these losses have not occurred since the inception of said indices (see Figure 10). The return-carnage in high quality assets this year is a result of a combination of very low yields over the last two years, and the amount of debt issued at those yields, giving fixed income a historically small cushion, alongside tightening monetary policy amidst the historically large shocks that we are experiencing today. A further anticipated tightening by the market, and/or unexpected withdrawal of liquidity by central banks will potentially make these drawdowns even worse.

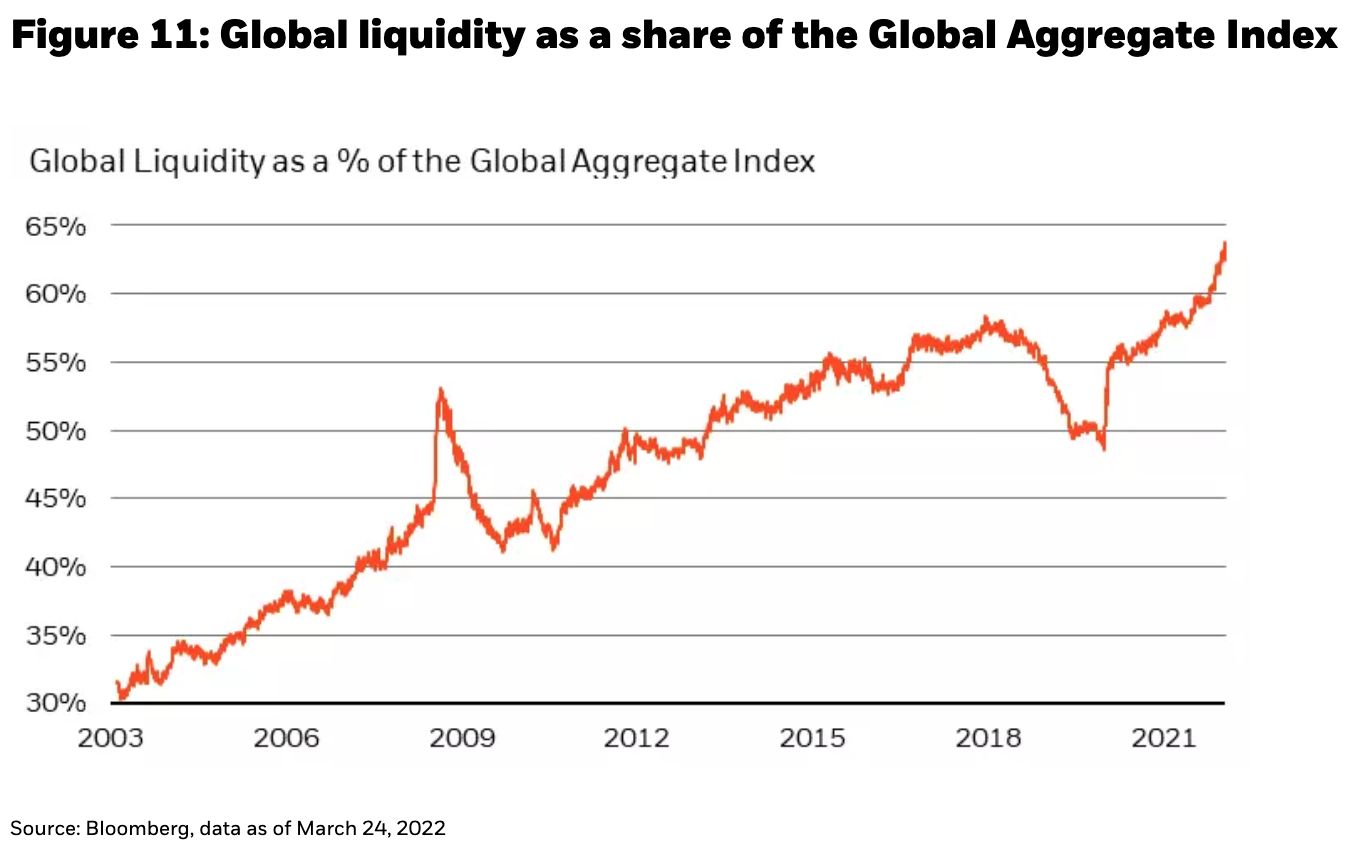

Although the near-term trend in investment flows can be negative, and the “if’s” are still very significant, one must consider the underlying supply/demand dynamics for financial assets today (see Figure 11): the need for financial assets (returns) exceeds financial liabilities (payout obligations). And with net worth growth slowing, but still quite high, the need/desire to earn a return on that net worth continues to be historically high.

We like accumulating assets that are offering a historically attractive return profile, such as the front-end of the high-quality fixed income market, the front-end and belly of credit markets (both Investment Grade and High Yield), municipal bonds, and even parts of emerging market hard currency debt that have taken a beating. These assets are near the cheapest they have been in a decade, and in the case of U.S. corporate credit, could even be considered cheap relative to equities (see Figure 12).

Yet, fixed income could get cheaper still in an environment fraught with “ifs” and has recently failed to offer diversification benefits against equities, a correlation regime that continues to warrant a cash allocation in portfolios. While there will be incessant chatter about the flattening of the yield curve, implying an underperforming front-end and inviting talk of a recession, it is duration risk that matters most for investors. Front-end yields that optically underperform today do not necessarily translate into underperforming returns tomorrow: in fact, 1-to-3-year bonds have a forward return profile that crushes that of longer duration bonds (see Figure 13).

Hence, investing in today’s markets feels a bit like being a security guard – there is a lot of watching of unprecedented environmental shocks, some of which occur after a long period of waiting for new information. But when periodic disturbances in markets do occur, action becomes necessary. Just as a security guard gets paid to wait, watch and then act, when necessary, today we like owning high-quality, short-duration assets that allow us to capture above-average yields, after the worst drawdowns in decades, while “watching and waiting to act,” with the knowledge that a few more months of data could bring a lot more clarity on which “ifs” transpire into which “thens.”

Rick Rieder, Managing Director is BlackRock’s Chief Investment Officer of Global Fixed Income and is Head of the Global Allocation Investment Team.

Rick Rieder, Managing Director is BlackRock’s Chief Investment Officer of Global Fixed Income and is Head of the Global Allocation Investment Team.

Russell Brownback, Managing Director is Head of Global Macro positioning for Fixed Income.

Russell Brownback, Managing Director is Head of Global Macro positioning for Fixed Income.

Trevor Slaven, Managing Director, is a portfolio manager on BlackRock’s Global Fixed Income team and is also the Head of Macro Research for Fundamental Fixed Income.

Trevor Slaven, Managing Director, is a portfolio manager on BlackRock’s Global Fixed Income team and is also the Head of Macro Research for Fundamental Fixed Income.

Navin Saigal, Director, is a portfolio manager and research analyst in the Office of the CIO of Global Fixed Income, and he serves as Chief Macro Content Officer.

Navin Saigal, Director, is a portfolio manager and research analyst in the Office of the CIO of Global Fixed Income, and he serves as Chief Macro Content Officer.