by Hubert Marleau, Market Economist, Palos Management

In the first 2 days of this week, investors extended the Thursday-Friday turnaround in the stock market from the previous week into a powerful rally, which ended on Wednesday. In just 4 days the S&P 500 jumped 262 points or 6.1%. Unfortunately, the fallout from Facebook’s dramatic post-earnings miss and concerns over Apple's new privacy ad-policy plunged Meta Platforms by 25% torpedoing the market on Thursday, thereby undermining risk sentiment and threatening to upend the nascent rally. On Friday morning, Amazon launched a rescue mission, crushing earnings expectations and doubling its net income from a year earlier.

This worked successfully and was better than expected. The skew index, a gauge that measures tail risk anxiety, decreased to 129.0. Overall the broad benchmark rose 69 points or 1.6% to end at 4501. Despite the distressing jolt in the market during the opening weeks of 2022, there’s been no capitulation and no massive allocation shift away from stocks. More than $20 billion flowed into equities last week, bringing the year-to-date inflow to $106 billion. The market is currently sandwiched between support (4300) and resistance (4625): the 50-DMA versus the 200-DMA. The market is in a tug of war between bulls and bears.

The likes of Netflix, Paypal, Zoom and Docusign clearly showed that growth stocks have a larger problem than just rising interest rates. Looking ahead, FAAMG may need to grow through acquisitions like MSFT just did with Activision Blizzard or through revisions of business models like Facebook converting to Meta Platforms Inc. America’s five technology superpowers are very rich, full of ideas and still growing, including Facebook. They have infinite resources and are therefore able to stay on top. In an editorial piece, the New York Times stated: “Their products are so in demand that even obscure pieces of their kingdoms are insanely popular.” This handful of companies has become enmeshed in our lives, economies and brains, such that we cannot imagine anything different.

Had it not been for them the economy would not have been able to support the heavy load of the pandemic. Moreover their dynamism should provide a digital environment conducive to raise the productivity of most businesses, combat the taxing effect of rising energy and food prices and perhaps help the Fed to engineer a soft landing.

Maintaining lofty sales increases may become difficult if the pace of the personal disposable income continues to slow down and the composition of consumer spending continues to shift in favour of services. This set of data points, which characterised the make-up of the economy, is starting to resemble those that prevailed in the latter months of 2019.

Firstly, food and energy prices have more than doubled over the past twelve months, nearing record levels. This definitely and obviously taxes the personal income of the middle class. Real disposable income is down 2% from last year and the personal savings rate is back to where it was pre-pandemic. Meanwhile, the pandemic spending habits of consumers is changing. More and more money is being spent on services rather than goods.

Should these three aforementioned changes persist, the growth factor and inflation rate will abate. Demand for home loans, mortgage refinancing and auto loans is declining. The Atlanta Fed’s NowCasting model is predicting that the pace of the economy could slow down to an annual rate of only 0.1% in Q1 of 2022. However I don't believe that the anticipated fall will be that dramatic. Demand for commercial loans is picking up smartly as businesses are building inventories, investing in capital formation and hiring workers. In the last three months ended January 2022, the number of jobs rose by almost 1.7 million. The unemployment rate ticked up to 4.0% because a lot more people joined the labour force.

The stunning jobs reports defied forecasts that the Omicron variant would hobble the labour market. The thing is that people are fed up with years of restrictions: armed with triple vaccinations and heightened immunity, they are looking to return to normal. They are seeking ways to socialise, play, travel, dine and-yes-work. Humans are social animals. They’ve had it with lockdowns and want to be out there in the world in spite of the risks that it may entail. BMO’s Ian Lyngen and Ben Jeffrey wrote: “ After all, logic holds that if hiring momentum can withstand Omicron, there is dwindling pandemic risk as the year unfolds.”

Secondly, the blowout January job report ups fear of Fed aggressiveness, cementing a 25bps interest rate in March and making a case for a 50bps increase. However, it should be noted that the neutral rate, where economic growth co-exists with price stability, is much lower than the Fed’s dot-plot terminal policy rate forecast. Given that the private savings-investment equation is out of whack because of huge government budgetary deficits and that reserve hoarding by the banking system is unusually large, the Fed is limited as to how fast, how much, and for how long it can tighten its monetary stance. Based on where the 5-year Treasury yield currently stands, its policy rate is not likely to exceed the 1.25-1.50% range. As a matter of fact, for weeks the monetary base has been declining, while Treasury Fed deposits have been rising. Consequently, the pace of the money supply is already decelerating and the bond-purchasing program has not yet stopped.

Consequently, a surge in productivity and the myth of the resignation of workers could help the Fed to bring the economy to a “three-plus-three” scenario by 2023, especially if the surge in productivity were to persist as expected. That is 3% for growth and 3% for inflation. A new regime that would closely resemble the one that defined the pre-pandemic era: but one step higher.

The BLS made it official this week that productivity gains have been extremely strong, labour productivity having grown at a 6.6% annual rate in Q4. For the whole of 2021, productivity rose 1.9%. Indeed, with firms having strong incentives to be more efficient and creative, better productivity may still be on the way. The wish to work from home combined with the need to modernise ordering systems, logistics, the mechanisation of production, and business models, is forcing companies to spend a lot of money on tools, training and capital formation. On an even bigger scale, they are acquiring intangible assets like intellectual property; investing in human capital; and broadening the utility of digitalisation to stimulate productivity quickly.

These signal decisions should raise productivity growth above the median of the last 20 years to +2.0%: doubled the pace of the cycle following the financial crisis of 2008-09. Research conducted by Deutsche Bank’s Mattthew Luzzetti suggested that nonfarm business sector productivity could accelerate to an annual rate of 3.5% or more over the next 2 years. All else equal, the acceleration would favour corporate earnings and wage rates without creating unwarranted pressure on inflation. Labour compensation, meanwhile, rose at an annual rate of 6.9% in the December quarter. But when one factors in productivity, unit labour cost increased only 0.3%, dragging down the year-over-year rise to a 3.1%.

I think that the average investor is unaware that the S&P 500 is up 35% from the pre-pandemic high of 3400. Interestingly, the current P/E ratio is 19.9x, roughly the same as the one that prevailed back then (February 2020). This shows that the true force behind the rally has been corporate profits. If forecasts of future productivity prove to be right, the Fed may not need to raise interest rates more than 4 times. Another big point is that the spread between 10-year and 2-year bond yields was 15 bps versus 65 bps today: the neutral rate was exactly the same (150bps), and the DXY was stronger (99 versus 96). Back then too, the talk on the street was about recession, compared to inflation today.

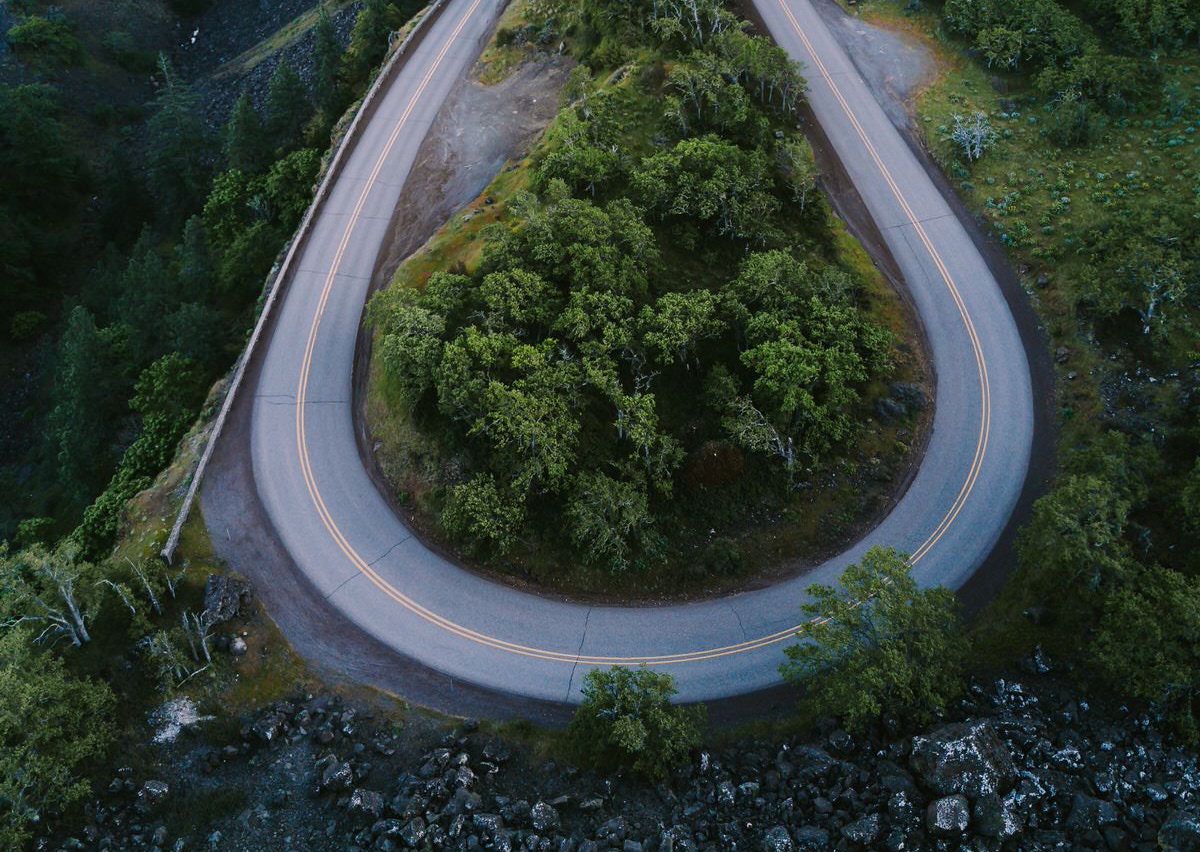

Since 1970, there have been 8 starting points to raise interest rates, but only one starting date (1971-1974) brought about a full-cycle decline in the S&P 500. That decline was 7.5%. Investors will feel a need to adjust to the reality that the economy will eventually move from its “growthflation” phase to a more modest economic scenario next year. In this connection, I suspect that the forthcoming adjustment will cause the market to zigzag for the next few months, building a base that could bring about an upward movement in stock prices as inflation and growth abates, pushing central banks to relax their 2022-restrictive monetary stance.

At this point, we are in an inflationary expansion phase. Thus specific sectors like commodities, industrial real estate, energy, basic material producers and old school industrial stocks should do better than other sectors. The personal service, travel, hospitality and leisure sectors should be seriously considered because the economy will soon be fully reopened. However, over time, the economy will change its allure and money will be made with growth. That is why I’m cautiously dabbling in the tech (productivity enhancement) and health care (aging demographics) sectors.

.