Excess cash has accumulated in every corner of the economy.

by Carl Tannenbaum, Executive Vice President, and Chief Economist, Ryan Boyle, and Vaibhav Tandon, Northern Trust

Happy new year! We hope that those celebrating holidays at the end of 2021 were able to relax and enjoy the season.

I wasn’t able to relax as much as I had hoped. Gift giving was stressful: despite numerous admonitions to shop early (the better to avoid shipping delays), I got a late start. As I struggled to figure out presents for loved ones that would be in hand on time, my wife advised giving cash instead. It allows the recipient to get what they want, she noted, and it can be delivered instantaneously through any number of online platforms.

As I considered my wife’s suggestion, it occurred to me that policy makers have been acting on her advice for almost two years now. They have been handing out so much cash, in fact, that recipients haven’t been able to spend it all. The accumulation of all that money in the global economy will present both opportunities and problems in 2022.

When it first arrived, the pandemic represented a substantial threat to the global economy. There were no vaccines or proven therapies, and the unknowns surrounding it prompted a high level of risk aversion. Societies shut down very tightly, and tens of millions found themselves un- or underemployed. A global depression was a distinct possibility.

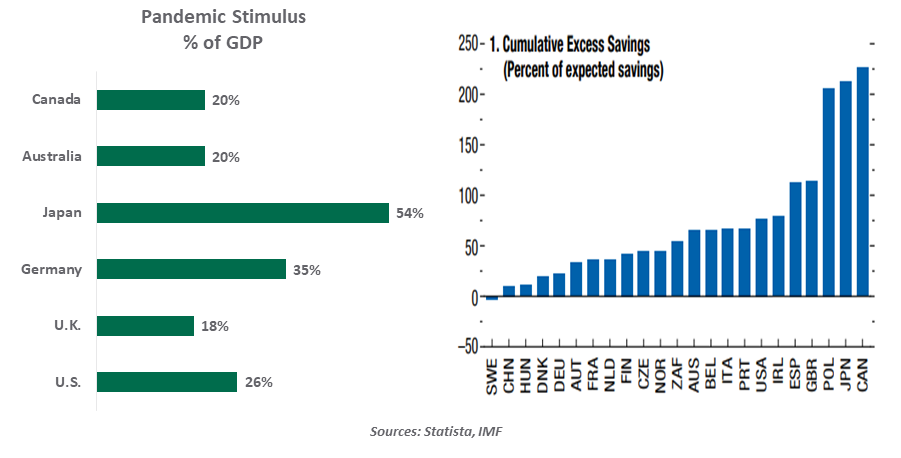

To offset the crash in private demand, governments stepped forward aggressively. Massive fiscal stimulus was applied, far in excess of what was passed in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis.

Funds were liberally distributed to households, both directly and in the form of unemployment support. Small businesses, many of them at risk of failure, were also a common target. Industries that were severely damaged, like travel and hospitality, were granted specific relief.

Governments preferred the risk of doing too much to the risk of doing too little. Speed was often stressed over specificity: the goal was to get money out the door as soon as possible. Even with this emphasis, some programs established in 2020 have yet to disburse their full allocations.

Those who received stimulus did not spend it all at once. Some felt the need to be cautious, given the unknown depth and duration of the pandemic. Others waited until economies reopened so that they could return to travel and leisure. The result has been a substantial buildup of excess saving, which stands as a potential driver of demand in 2022.

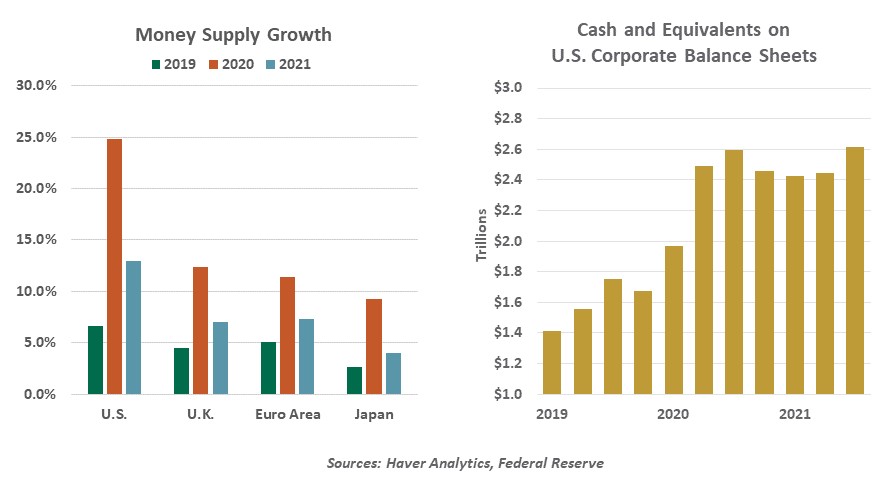

Financing the effort was not difficult. Investors were happy to snap up the additional issuance of sovereign debt, and central banks did their part through expanded purchases of government securities. The international money supply soared.

Excess cash has accumulated in every corner of the economy.

The result was a massive accumulation of cash on balance sheets. Corporations are holding much higher levels of liquidity than they did in 2019; banks have substantial fractions of their assets on deposit with their central banks; and saving rates remain well above normal in most countries.

It's been difficult to find parking places for all of that money. As the excess liquidity has been invested, asset prices have stretched relationships with fundamental values. Real interest rates are deeply negative. Nearly $1.5 trillion of excess reserves are reinvested every day with the Federal Reserve, at very low interest rates.

It has been clear for some time that the global economy no longer needs extraordinary measures. Nonetheless, additional spending programs are being contemplated in many countries. The pull of demand created by fiscal and monetary stimulus has played an important role in the development of inflation over the past year.

Monetary policy is clearly poised to tighten. The Bank of England has already raised rates, and the Federal Reserve could follow suit as early as March. The challenge for both, and for other world central banks, will be to drain enough cash from the financial system quickly enough to stem inflation in goods and asset prices. The scale of this exercise will be far larger than anything previously attempted. And having waited to begin the process, the program may need to proceed at a brisk pace.

The change of tack will have to be carefully communicated, to avoid unsettling financial markets. This effort is not off to a good start: The Bank of England surprised markets with its December rate hike, and the Federal Reserve has been rapidly revising the potential timing and extent of tightening. In addition, minutes from the most recent Fed meeting suggest that reductions in holdings of government bonds could commence much sooner than previously expected.

Because there is so much cash out in the economy, consumers and corporations have been using credit less frequently. Changing the cost of credit is one way that central banks can modulate economic activity, but that channel may not be as fluid when few are borrowing. As a result, interest rates may need to rise to higher levels to produce the desired restraint.

Having waited to begin sopping up excess liquidity, central banks may now need a bigger sponge.

All of this illustrates the peril of calibrating policy based on the last crisis or business cycle. The deliberate pace of policy normalization used seven years ago was appropriate for an economy that recovered gradually without stressing inflation. This time around, recovery has been more rapid, and inflation has become a significant risk. Normalization therefore needs to occur more rapidly, with less lead time between reflecting and reacting.

I wish I had spent less time reflecting and more time reacting during the holiday season. I’ve never been a big fan of giving cash gifts; the practice seems somewhat impersonal. In the end, though, I broke down and transferred funds to loved ones. And to ensure that the recipient didn’t feel under-recognized, I probably overcompensated. There is a lesson in there…at many levels.

Don’t miss our latest insights:

Revising Impressions of the Labor Market

Omicron Is Burning Brightly, But May Burn Briefly

Information is not intended to be and should not be construed as an offer, solicitation or recommendation with respect to any transaction and should not be treated as legal advice, investment advice or tax advice. Under no circumstances should you rely upon this information as a substitute for obtaining specific legal or tax advice from your own professional legal or tax advisors. Information is subject to change based on market or other conditions and is not intended to influence your investment decisions.

© 2022 Northern Trust Corporation. Head Office: 50 South La Salle Street, Chicago, Illinois 60603 U.S.A. Incorporated with limited liability in the U.S. Products and services provided by subsidiaries of Northern Trust Corporation may vary in different markets and are offered in accordance with local regulation. For legal and regulatory information about individual market offices, visit northerntrust.com/terms-and-conditions.