by Zhennan Li, Senior Economist—Greater China, AllianceBernstein

Renewed impetus behind China’s goal of “common prosperity” has raised concerns that Beijing plans a redistribution of wealth that could hurt growth and investment. The reality, however, is more nuanced—and a good deal more positive for China’s long-term growth ambitions.

Common prosperity first became a catch cry in China under Chairman Mao Zedong in the 1950s. Its revival under President Xi Jinping, at a time of heightened regulatory intervention in business, has been interpreted by some as evidence of Beijing’s increasing economic conservatism.

But China today is very different from what it was in the 1950s. Its policy actions can still puzzle outsiders, however, and the task of analyzing them can seem as arcane as reading tea leaves.

The key to understanding China’s new push for common prosperity is to look at it in terms of the country’s modern, growth-oriented economy. To do this, it helps to define what the government means by common prosperity, why Beijing is promoting the idea now and how it fits into the country’s long-term economic outlook.

What Common Prosperity Means

In a speech in August 2021, President Xi said that common prosperity, “rather than being egalitarian or having only a few people prosperous,” referred to “affluence shared by everyone.”

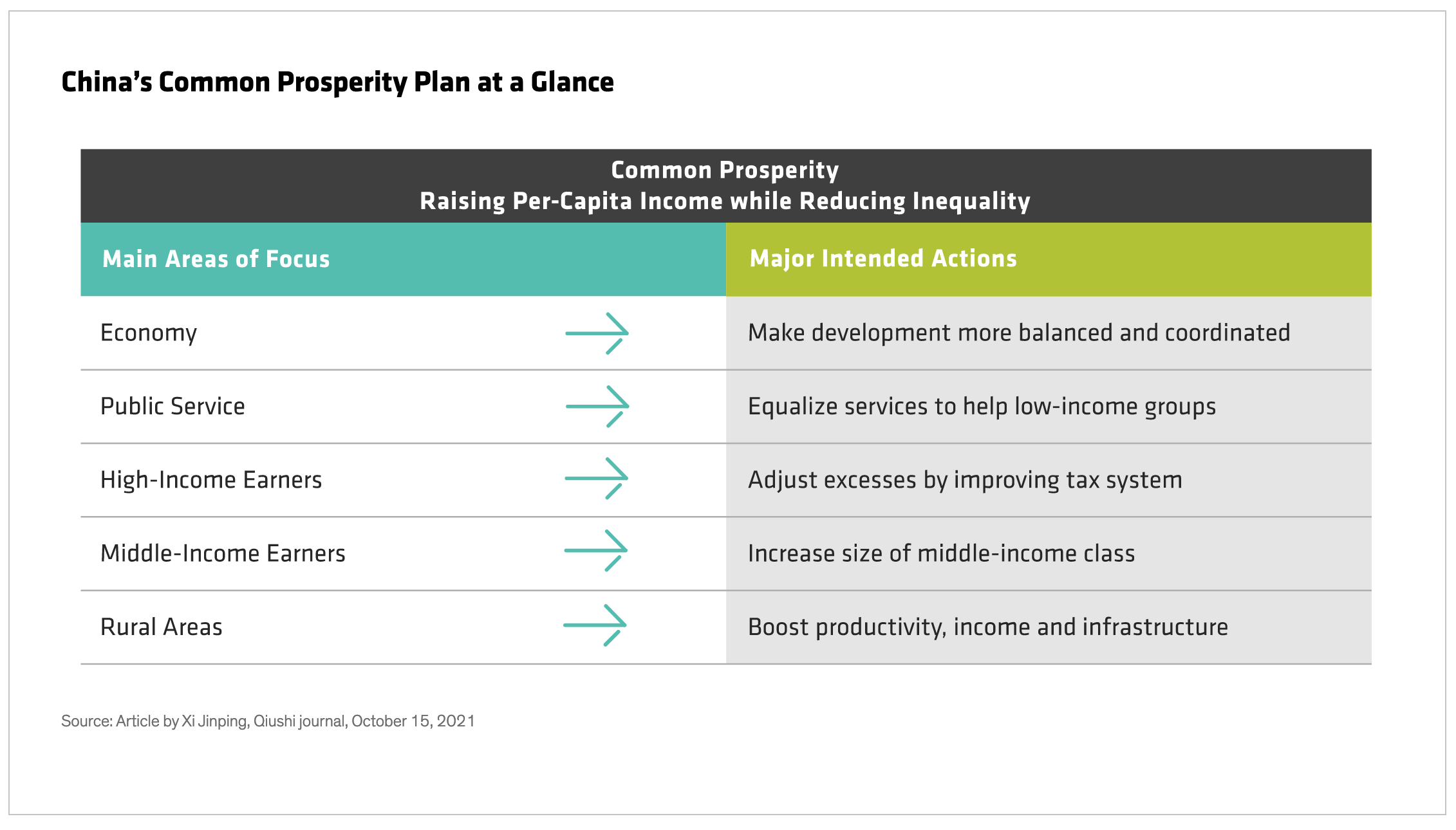

Its aim, in other words, is not to rob from the rich and give to the poor or to hurt growth, but to increase per-capita income and to reduce inequality across income groups and regions. The Display below summarizes the main policy areas that the initiative will target, together with intended actions.

Regarding economic development, the aim is to even out imbalances between regions, business sectors, and small and large enterprises. Regional development, for example, could be better balanced by fiscal transfers. In business, solutions would include faster monopoly reforms and closer coordination between the finance and property sectors and the rest of the economy.

Making delivery of public services more equal would be of particular benefit to low-income groups in terms of education, social security and other forms of aid, such as improvements in housing supply.

Income inequality would be addressed in part by tax changes focused on those deemed to earn excessively high incomes. These would include changes to personal income tax (income derived from capital is currently subject to a separate flat tax rate) and to property and consumption taxes.

Measures for expanding the middle-income group include improvements in higher education, better training and higher wages for skilled workers, lower tax and other benefits for small business owners and the self-employed, help for migrant workers, and salary increases for low-level public-sector employees.

Rural land reform, together with increased agricultural productivity and infrastructure investment, would lead to higher rural incomes.

There are several reasons for Beijing to launch this program now.

China’s Inequality Holds Back Growth

Some are political. Celebrating the Chinese Communist Party’s centenary in July 2021, President Xi said the goal of achieving a moderately prosperous society had been achieved, and that the next objective was to build a “modern socialist country.”

This would involve a gradual narrowing of inequality in household income and consumption by 2025 with substantial progress by 2035. Common prosperity would be broadly achieved by mid-century, when household income and consumption inequality had narrowed to a reasonable range.

Other reasons behind the push for common prosperity are economic. China’s potential growth has declined over recent years because of resource misallocation, with the imbalance between investment and consumption among the biggest in the world.

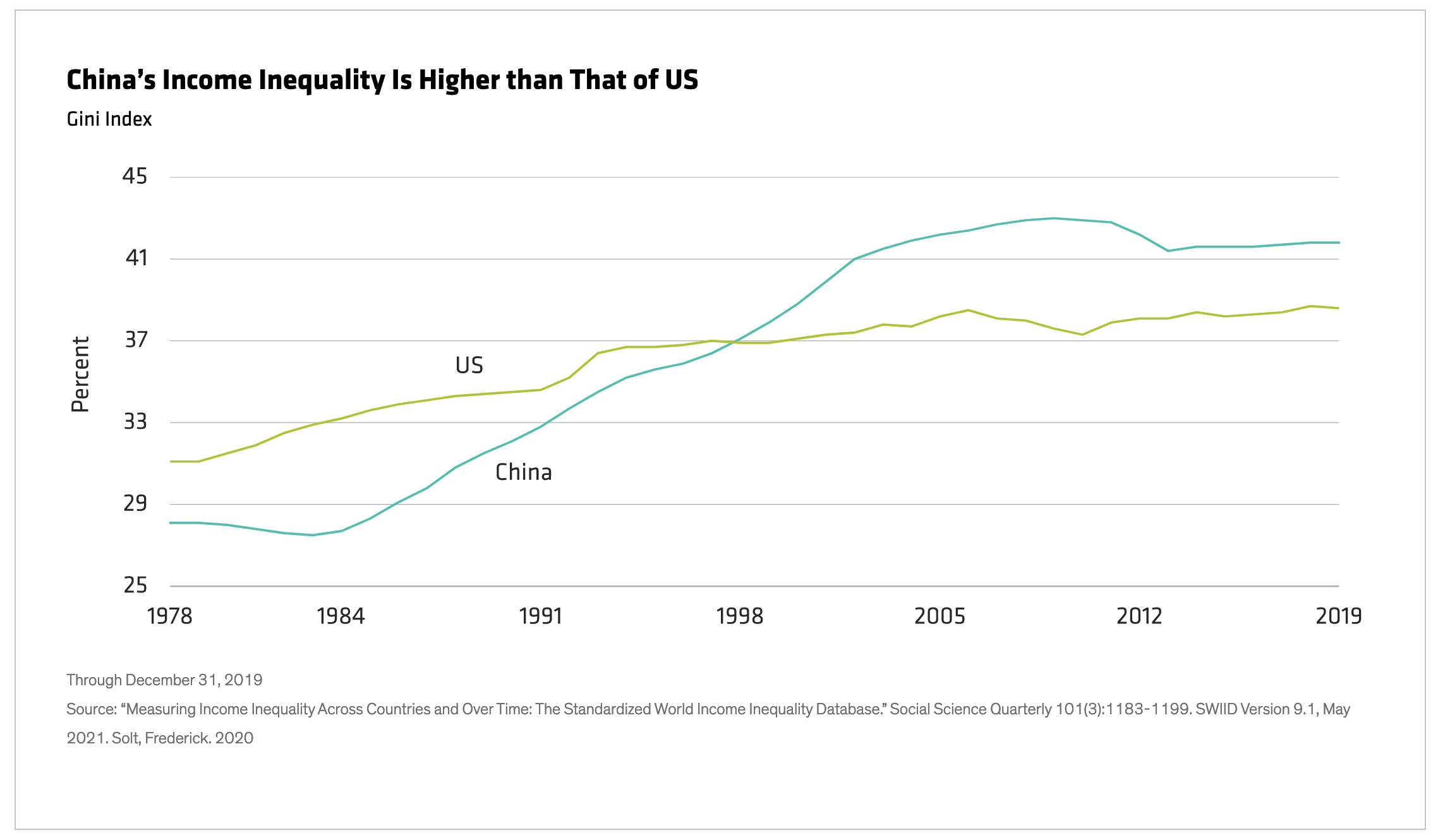

One reason for the low consumption ratio has been widening inequality. The Display below uses a Gini index (a measure of statistical dispersion) to show how income inequality has risen in China and the US.

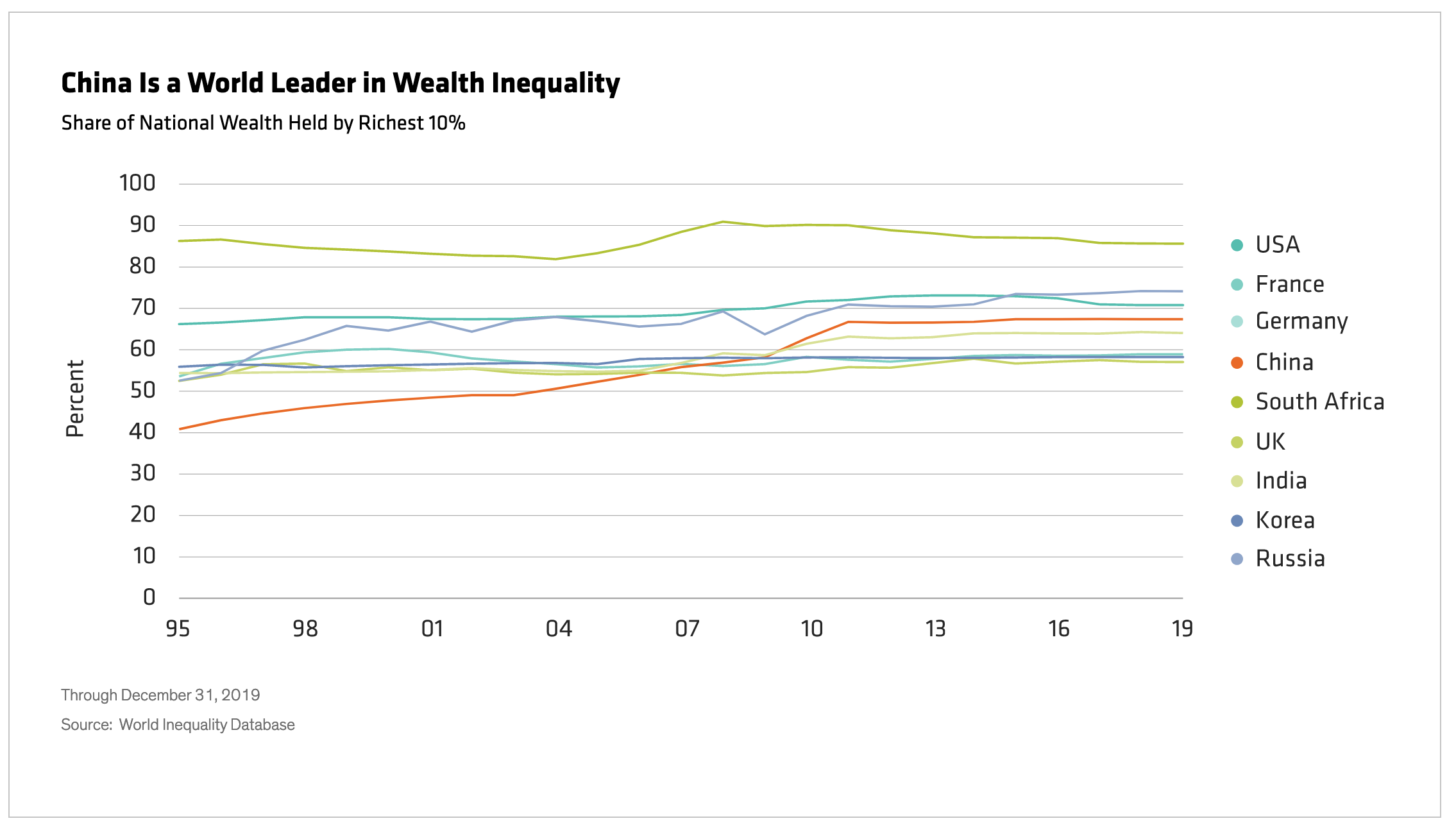

Wealth inequality has also trended sharply upward in China. The percentage of national wealth owned by the richest 10% is close to that of the US and is higher than in several other developed countries (Display).

By targeting inequality, Beijing hopes that common prosperity will help bring about better-balanced long-term growth.

Common Prosperity Serves China’s Long-Term Growth

In 2020, China announced a “dual circulation” long-term economic strategy through which it would reduce its dependence on exports (external circulation) in favor of more domestically driven demand and supply (internal circulation). The key to the strategy’s success lies in expanding domestic demand and carrying out structural reforms to the supply side of the economy.

Common prosperity—with its focus on balanced economic development and its potential to boost consumption—clearly has a role to play in supporting internal circulation. Other measures are needed to ensure the dual-circulation strategy’s success. They include increased innovation to revive growth in total factor productivity—a key long-term domestic growth driver that has lagged in recent years because of structural imbalances in the economy.

In our view, this is the proper context in which to view common prosperity. Far from indicating a shift to more regressive economic policies, it is firmly aligned with China’s overarching goal of achieving better-balanced long-term growth in the interests of a stable and more equitably wealthy society.

About the Author

Zhennan LiZhennan Li is a Vice President and Senior Economist for Greater China. In that role, he is responsible for economic analysis, FX and interest-rate forecasting, and bond market strategy for the Fixed Income team. Prior to joining AB in 2021, Li was a senior China economist at Goldman Sachs for almost six years. Previously, he served as a manager at China Development Bank in Beijing between 2013 and 2015. Li holds a PhD in economics from Peking University. Location: Hong Kong

Zhennan LiZhennan Li is a Vice President and Senior Economist for Greater China. In that role, he is responsible for economic analysis, FX and interest-rate forecasting, and bond market strategy for the Fixed Income team. Prior to joining AB in 2021, Li was a senior China economist at Goldman Sachs for almost six years. Previously, he served as a manager at China Development Bank in Beijing between 2013 and 2015. Li holds a PhD in economics from Peking University. Location: Hong Kong