Strikes and quits show workers are feeling emboldened.

by Ryan James Boyle, Vice President, Senior Economist, Northern Trust

Auto dealerships are known for attention-grabbing displays, from inflatable characters to vehicles perched on high platforms. Over the summer, I passed a local dealership that featured a sight I hadn’t seen for years: A picket line of mechanics on strike. As the year continued, strikes and other labor actions have become more commonplace, spanning sectors including healthcare, food production, manufacturing, and entertainment. Have workers entered a new era of greater power?

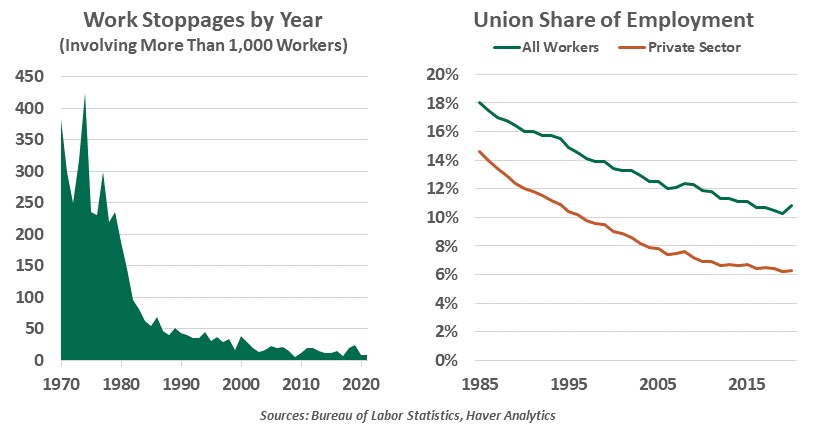

Large-scale strikes have become a rarity in recent decades, because private sector union membership is a shadow of the levels seen in past generations. The union share of the U.S. labor force peaked at 25.5% in 1953, and has been falling ever since. Right-to-work laws and skepticism surrounding the value of dues reduced the power of many unions, while fair labor standards and occupational safety laws have ensured some of the workplace protections that unions advocated in the past.

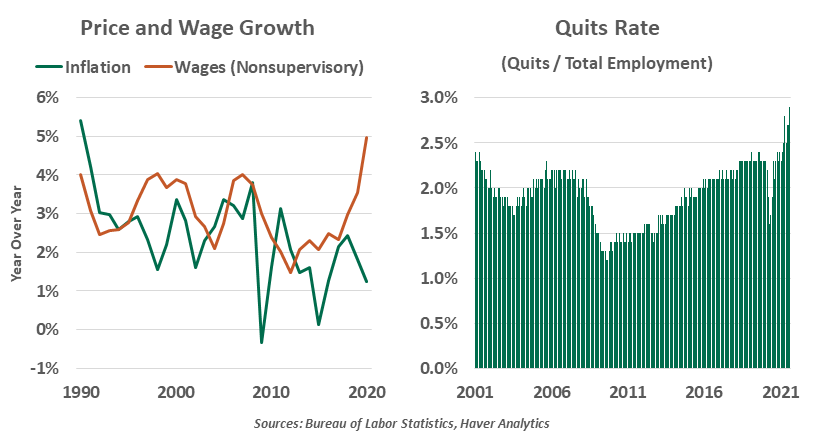

But a union card is not required to be emboldened. Non-union workers lack the organization that would allow for strikes, but they are seeking new opportunities on their own terms. The wide availability of jobs and high demand for employees has given workers more confidence that they can leave their current posts and find another job at higher pay. This has forced employers to up their own pay scales to sustain staffing.

Gig work like ridesharing and food delivery allows workers to fill in gaps in employment at their convenience. Employers are learning to adapt, moving away from rigid nine-to-five schedules and toward flexible hours. Some employers are even shortening pay periods so that workers are more immediately rewarded for the work they do, competing with gig platforms that make daily payments.

Inflation concerns are leading workers to demand higher wages. In most recent years, wages rose more rapidly than inflation; today, the opposite is true. As workers secure better increases, firms may be prompted to raise prices, initiating a feedback loop that could be difficult to arrest.

High inflation and high market wage offers are prompting workers to ask for raises.

Some of today’s strikers are resisting the outcomes of past labor compromises. To manage rising pension costs, some employers put a two-tier compensation structure in place, where new hires were placed on a different wage scale or had less generous benefits. Today, those workers seek to be treated equally.

Raises are not the only requests coming from labor. Some workplaces have shut down in protest of excessive demands for overtime and too few days off. Workers who have stayed employed through the crisis are growing tired of working extra shifts, shorthanded. Many of these workers were labeled essential and celebrated for their efforts. Today, faced with constant demand and stagnant wages, they are seeking a reward for working through a pandemic.

Workers’ timing is right. Corporate profits have climbed in the course of the recovery. Equity markets are thriving, and workers expect to share in those rewards. Corporate treasuries are in a good position to increase compensation.

And workers’ leverage is strong today. The job market remains highly dislocated, with twice as many job openings as displaced workers. Those participating in labor movements know that their managers will struggle to recruit replacement staff, let alone train them. Managers are sometimes forced to fill in for striking line workers, with mixed results.

Physically-demanding worksites, like mines and factories, are particularly struggling to hire. Manufacturing was often viewed as a sector that offered good wages and steady work, especially for workers with less education. However, sectors like retail and warehousing are typically more tolerable, less dangerous work environments than factories. As wages in these areas catch up to those offered by manufacturers, recruiting and retaining factory workers is a growing challenge.

Strikes carry high costs. Businesses immediately suffer from reduced output and negative attention in their communities, and their labor costs are at risk of permanently rising. Workers are also making a gamble: Unions may offer a small amount of strike pay, but it does not replace workers’ usual earnings. If a strike fails to yield material improvements, workers may end up worse off for having organized.

Is this new era of worker empowerment going to last? One gauge suggests it could be temporary: There has not yet been a notable increase in unionized workplaces or union membership. An attempt to unionize an Amazon warehouse earlier this year was roundly defeated by the local workforce. If unions can capitalize on this moment to demonstrate their value, they could reverse their long-running membership decline.

Though strikes attract headlines, elevated quits show all workers are feeling emboldened.

Union organizers have a political tailwind at the moment. The Biden administration is unabashedly pro-union and has expressed support for greater labor organization. Turning that campaign theme into policy, however, will not be easy. Labor reforms will face an uphill battle in a tensely divided Congress, and the few proposals that have been floated thus far received a lukewarm reception. For example, a proposal to offer greater tax credits for purchases of union-made electric vehicles promptly drew international criticism. Still, unions are enjoying more attention today than they have had for many years.

Despite continued job gains, over four million fewer people are working today than were employed before the COVID crisis. Factors from childcare to health concerns have kept them out of the workforce thus far. However, the economy has caught up to its pre-COVID size, despite this labor shortfall. Workers are still needed, and they know they are in a strong negotiating position. Picket lines may become a more familiar sight.

Don’t miss our latest insights:

Central Banks Try To Stay Ahead of the Curve

Information is not intended to be and should not be construed as an offer, solicitation or recommendation with respect to any transaction and should not be treated as legal advice, investment advice or tax advice. Under no circumstances should you rely upon this information as a substitute for obtaining specific legal or tax advice from your own professional legal or tax advisors. Information is subject to change based on market or other conditions and is not intended to influence your investment decisions.

© 2021 Northern Trust Corporation. Head Office: 50 South La Salle Street, Chicago, Illinois 60603 U.S.A. Incorporated with limited liability in the U.S. Products and services provided by subsidiaries of Northern Trust Corporation may vary in different markets and are offered in accordance with local regulation. For legal and regulatory information about individual market offices, visit northerntrust.com/terms-and-conditions.

Ryan James Boyle

Ryan James Boyle

Vice President, Senior Economist

Ryan James Boyle is a Vice President and Senior Economist within the Global Risk Management division of Northern Trust. In this role, Ryan is responsible for briefing clients and partners on the economy and business conditions, supporting internal stress testing and capital allocation processes, and publishing economic commentaries.