by Liz Ann Sonders, Chief Investment Strategist, and Kevin Gordon, Charles Schwab & Company Ltd.

Special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs)—also known as blank-check companies—have gained immense popularity among investors since the beginning of 2020, despite being around for decades. Offering an alternative way for companies to go public, SPACs themselves are publicly traded investment vehicles whose purpose is to bring target companies public through the process of a merger. SPACs are incredibly complex vehicles and can differ widely in size, structure, and quality, among other things.

SPACs’ goal: A faster path to public markets

The traditional initial public offering (IPO) process can be quite arduous from both a funding and regulatory perspective. Companies intending to go public embark on a long process to gain investors’ interest and investments, as well as clear regulatory hurdles. In general, SPACs aim to alleviate some of those burdens by promoting a faster and less expensive path to the public markets. The creation of the SPAC starts with a sponsor—ranging from a private equity firm to a former corporate executive—who works with an underwriter to bring the company public. After the SPAC goes public, investors are able to buy and sell shares as they would with any other public equity.

Typically, SPACs then have two years to find a company with which to merge. If a target is not found, the SPAC liquidates and distributes funds back to shareholders, and the sponsor loses its investment.

SPACs’ popularity has exploded

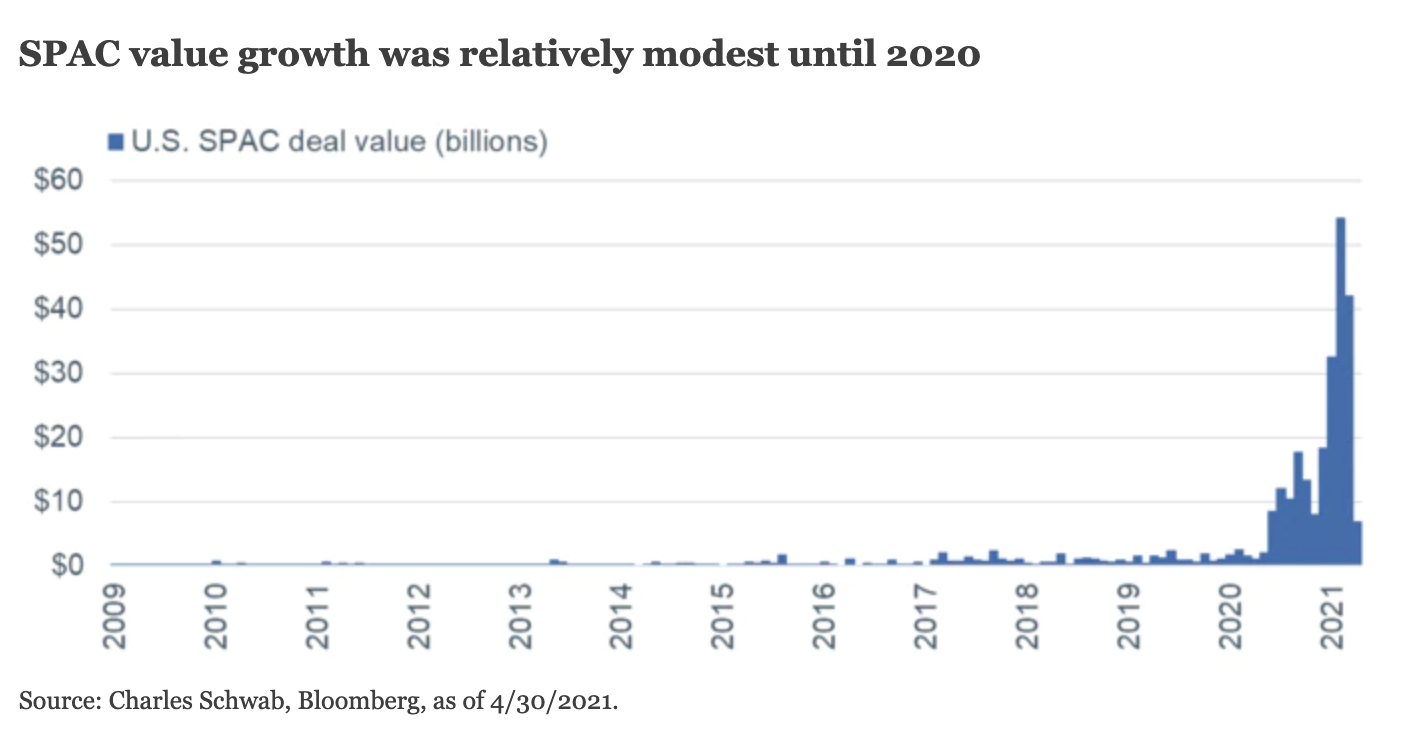

As mentioned, SPACs are not new phenomena and have existed for decades, yet their popularity has exploded in recent years. As you can see in the chart below, total SPAC value has climbed exponentially on a monthly basis over the past year. February 2021 alone saw over $50 billion in deal value, with value in the first quarter of 2021 exceeding the amount seen in all of 2020. Some air has been let out recently, thought, evidenced by the marked decline in April volume.

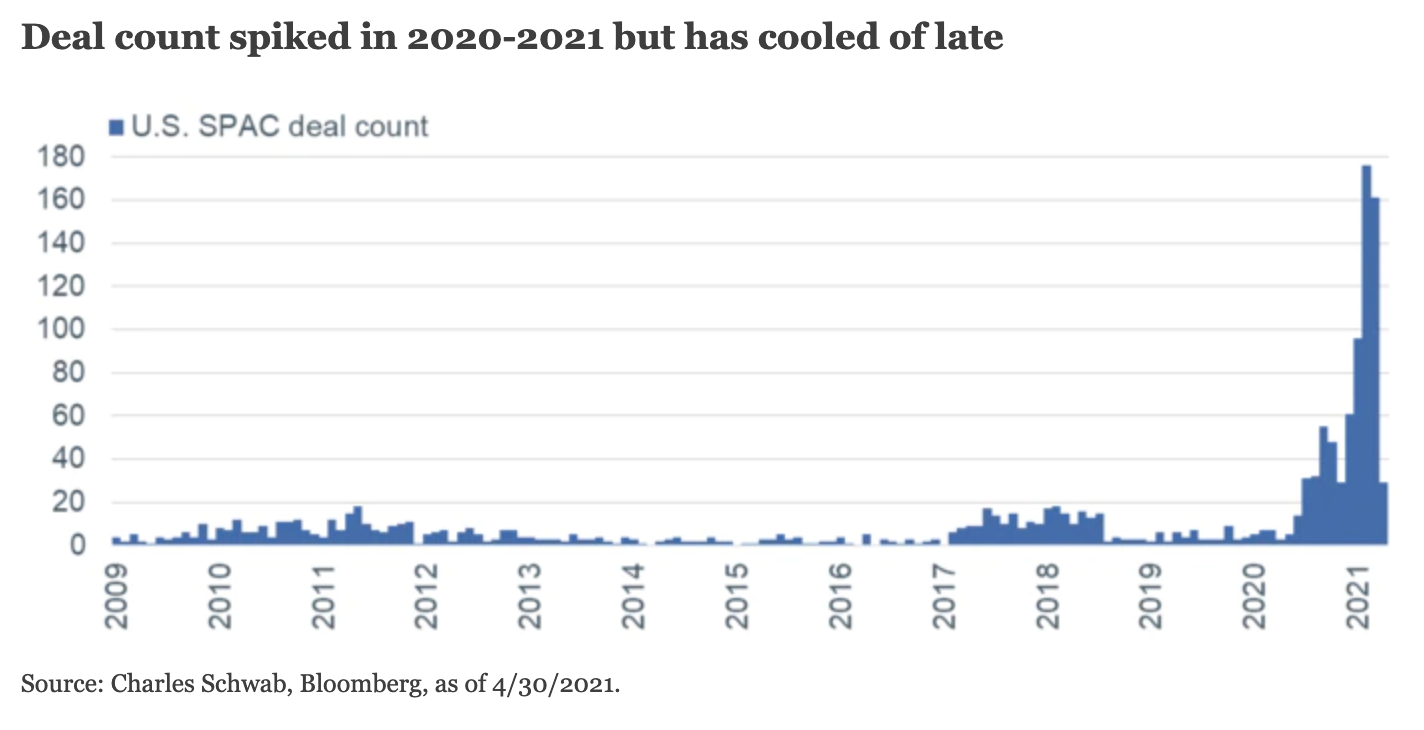

The chart below shows that the number of SPACs has also seen a spike in growth. Almost 180 SPACs were announced in February 2021; again, the number of companies launched in the first quarter of 2021 exceeded the total seen in all of 2020. Yet, similar to the aforementioned decline in value, the number of new deals fell sharply in April.

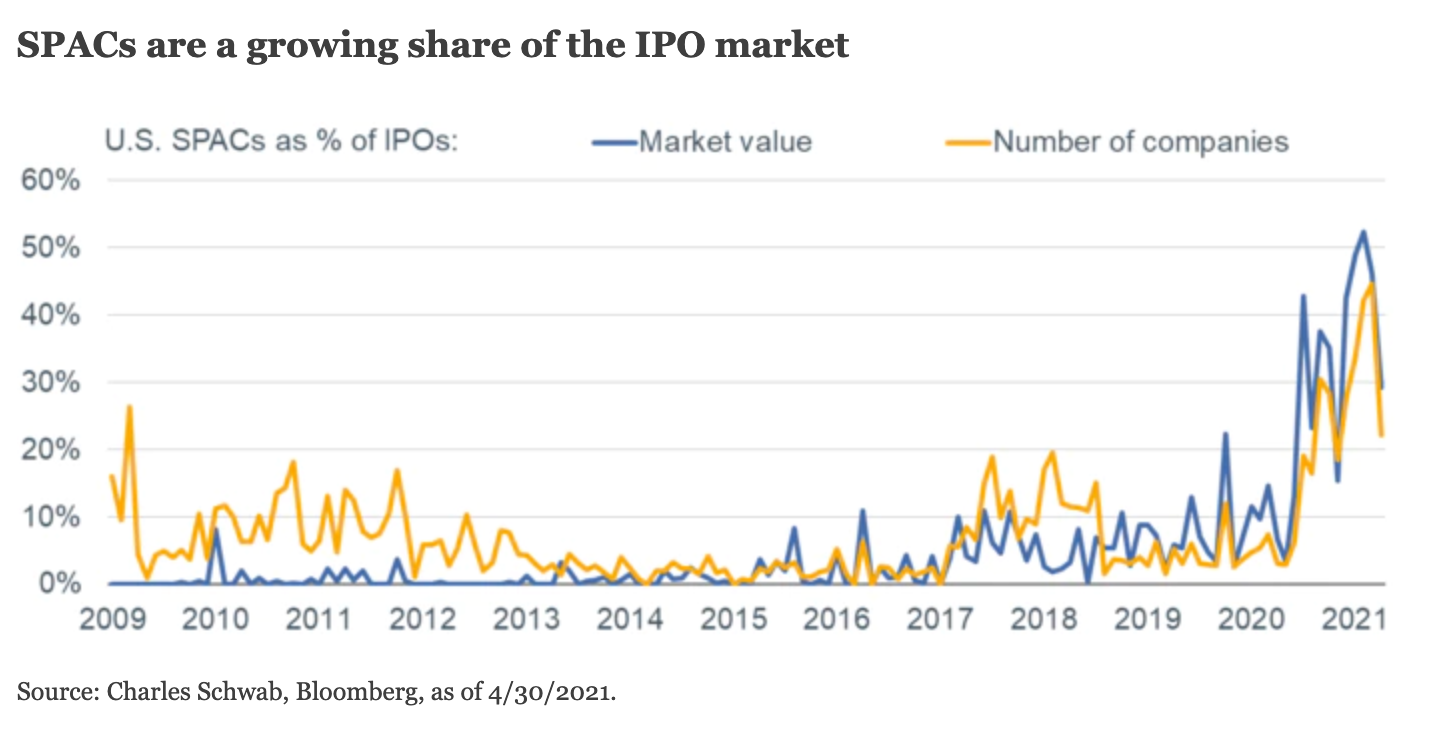

The massive growth in both value and deal count led to SPACs’ increasingly large share of the U.S. IPO market. The chart below shows that in February 2021, their market value accounted for just over half of the value of IPOs. The share was slightly less for the number of companies, but incredibly high nonetheless.

Evidenced by the severe tick down in value and deal count in April 2021, activity has cooled. Part of that is due to a simple supply and demand imbalance. With a large number of active SPACs now looking for merger targets, the playing field has grown increasingly competitive. Given the two-year limit on the search process, a potential risk is that companies settle for lower-quality targets—thus risking future success—or fail to find a target outright and are forced to liquidate.

How do returns measure up?

Along with the advertisement of lower fees and smaller regulatory hurdles, SPACs’ popularity has stemmed from their association with celebrities, ex-hedge-fund managers, and former corporate executives. In many cases, that has helped boost their allure and performance, regardless of whether they have found and merged with a target company. While it is true that many SPACs have performed well, there are important distinctions to note.

Importantly, fee structures vary widely and may not be as attractive as proposed. After taking into account the sponsor’s equity stake—which usually amounts to 20%—and other banking fees, the cost to public investors at the time of the SPAC’s IPO and/or merger with a target company is at times much higher than what is normally seen for a traditional IPO.

In general, SPACs have seen their strongest gains from the time of their IPO up until they find a merger target; conversely, their weakest performance has come after a successful merger. Researchers found that between 2010 and 2020, buying a SPAC at its IPO and selling it at the time of merger would have yielded a return of 9.3% annually. For SPACs held for a year after a merger, the annualized loss was 15%. 1

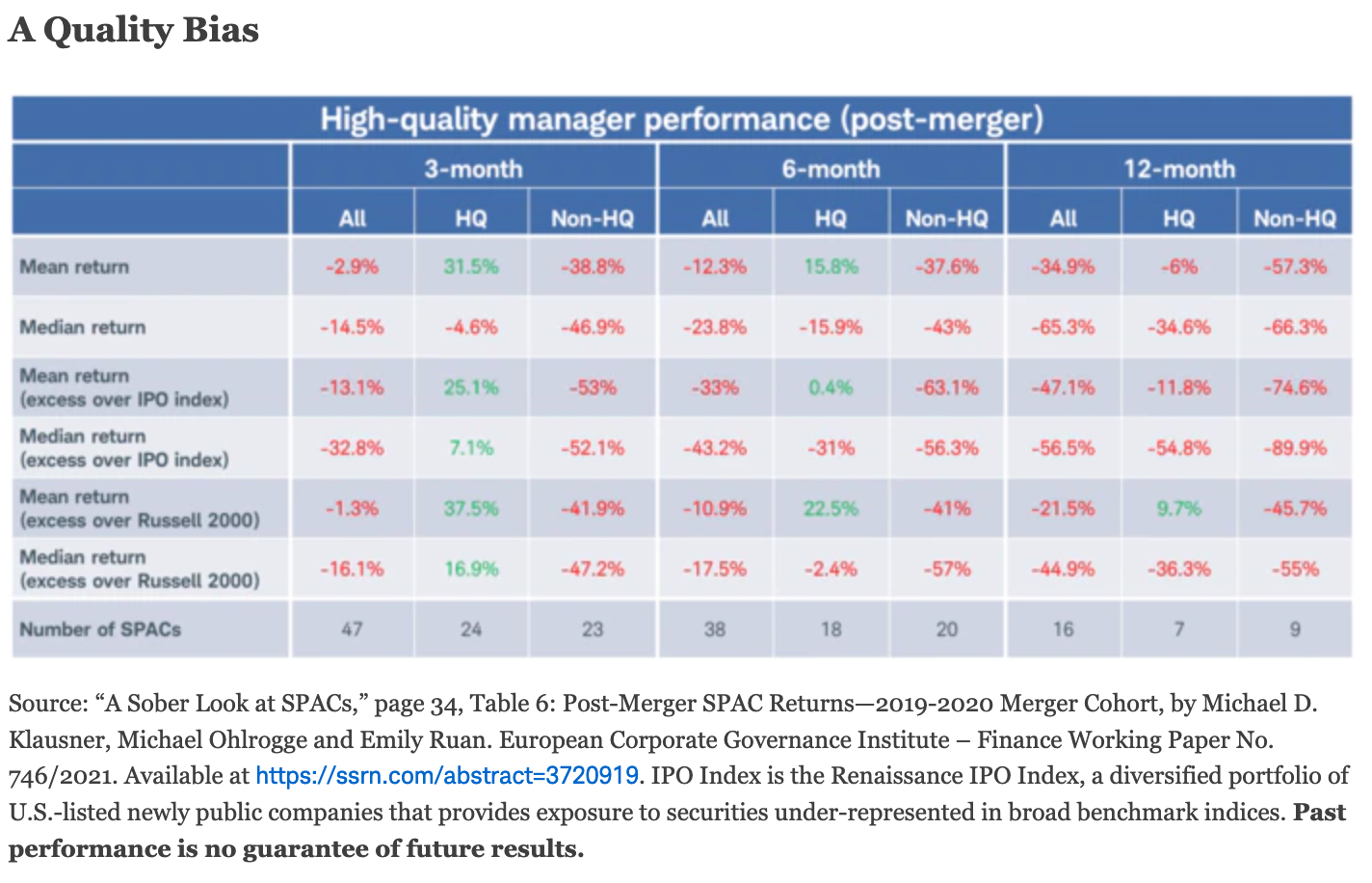

Quality is also an important factor to consider. High-quality managers—those who were formerly senior officers at a Fortune 500 company and/or affiliated with a fund managing at least $1 billion—have achieved much stronger returns than non-high-quality managers.2 As shown in the table below, they also had higher returns in excess of the broader market (measured by both the Renaissance Capital IPO and Russell 2000 Indexes) than non-high-quality managers in the three, six, and nine months following a successful merger.

What does this mean for the market?

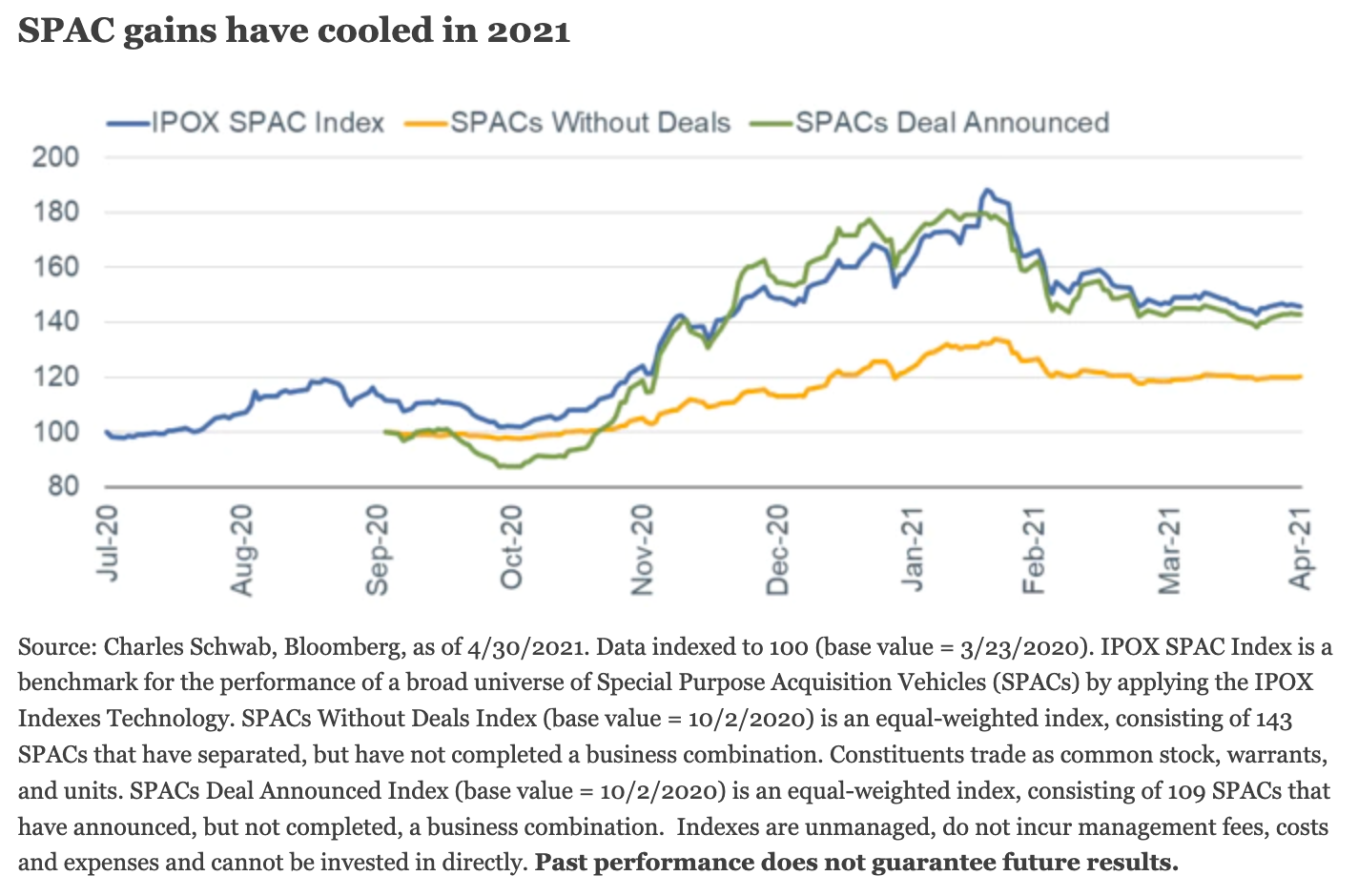

SPACs have been caught up in the group of speculative trades that took off last year. Yet, similar to heavily shorted stocks, non-profitable technology companies, and stocks favored by retail traders, SPACs’ performance has taken a breather since the start of this year. The chart below shows the IPOX SPAC Index—a broad universe of SPACs—along with two other indices that track firms with and without completed deals. All three are relatively new, yet in their short lifespan, they’ve seen impressive gains. Both the IPOX SPAC Index and that tracking SPACs with deals announced nearly doubled by late-January. Since then, performance has come off the boil, with both suffering their own bear markets (at least a 20% decline) from peak-to-recent-trough.

Although down 12% at the worst point this year from the peak, SPACs without deals have experienced more modest losses. Still, their longer-term performance remains muted relative to those with deals announced, underscoring the research showing investors’ decreasing willingness to hold their shares as the merger approaches and/or is completed.

The strong performance and exponential growth of blank-check companies has unnerved some investors. SPACs trade on virtually no fundamentals pre-merger, and if/when they do find a company to bring public, there is no guarantee the target itself is or will be profitable. Unlike with the traditional IPO process, the SPAC route doesn’t restrict target companies from discussing paths to future revenue. These aspects vary on a case-by-case basis, but the potential for a lack of profitability for the foreseeable future can render some SPACs quite speculative in nature.

Given heightened speculation, many investors have characterized the current market as reminiscent of what we saw in the late 1990s. The tech boom—propelled by many unprofitable companies going public—resulted in an epic collapse across markets, with the NASDAQ 100 bearing the brunt, resulting in its 83% fall from March 2000 to October 2002.

There remains a risk that the SPAC market’s continued growth and subsequent larger share of the overall market will stoke further speculation. As was the case with the tech boom in the late 1990s, a pickup in momentum may amplify losses, given the proliferation in the number of blank-check companies. For now, the SPAC frenzy has mostly been isolated, and some of the severe declines haven’t translated into the same degree of weakness for the broader market.

Regulatory scrutiny is heating up

Given heightened speculative activity around SPACs, it’s no surprise that they’re increasingly in the sights of regulators—including the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). Speaking in April at a legal conference, John Coates, acting director of the SEC’s Division of Corporate Finance, said there were “some significant and yet undiscovered issues” with SPACs, given they bypass some traditional safeguards of the IPO process. “Their current surge is bringing the level of attention by many more participants in the market than previously had been involved, and that is turning up some questions that have to be thought through more carefully,” Coates said.

A late-April report from the SEC also hinted at the possibility that SPACs may need to account for warrants (securities issued to early investors) as liabilities, rather than as equity. The potential shift would force many companies to reword their previously audited financial statement—not a fatal threat to SPACs themselves, but a potential restriction on the speed with which deals can advance.

Bottom line

Despite the abrupt halt in overall activity in April, interest in SPACs remains very high, which has boosted both the number of blank-check companies, and their share prices, at breakneck speeds. Given the variable nature and structure of each company, risks vary widely and are increasingly being scrutinized by regulators.

Their rapid rise has reflected a rash of speculative behavior, but the market has so far proven to be resilient in the face of some SPACs’ marked declines—which have become much more widespread. That has kept them from infecting the broader market but, as with any investment, they carry a set of risks that should be analyzed carefully.

1 Gahng, Minmo; Ritter, Jay R.; and Zhang, Donghang, “SPACs,” Warrington College of Business, University of Florida and Darla Moore School of Business, University of South Carolina, March 2, 2021. Available at https://site.warrington.ufl.edu/ritter/files/SPACs.pdf

2 Klausner, Michael D.; Ohlrogge, Michael; and Ruan, Emily, "A Sober Look at SPACs," European Corporate Governance Institute - Finance Working Paper No. 746/2021. Available at https://ssrn.com/abstract=3720919