by Darren Williams, AllianceBernstein

Widespread lockdowns have resulted in record output declines and soaring debt across the euro area. But the political response to the COVID-19 crisis may be positive for the European integration project—and for euro-area bond markets.

Last year, governments across Europe locked down their economies in order to control the spread of COVID-19. Not surprisingly, this resulted in record output declines. This year, as vaccination programs finally gain traction, governments are starting to reopen their economies, a process that will inevitably yield unprecedented output gains. For the most part, these increases will be predictable and artificial, telling us very little about the euro-area economy’s longer-term prospects.

COVID-19 Shock Brings Important Changes

So, which recent changes will have a significant and lasting impact? In economic terms, both the mammoth increase in government debt and the widespread acceptance of money-financed fiscal activism will affect the longer-term outlook for growth and inflation. But COVID-19 is also likely to cause significant political disruption—positive and negative.

In fact, political change has already started. Last year, for example, COVID-19 provided the impetus for EU leaders to agree on a €750 billion recovery fund. While this was not quite Europe’s “Hamilton” moment, it did represent an important step towards joint borrowing and, perhaps one day, debt mutualization. It’s hard to believe this would have happened in the absence of a significant common shock.

COVID-19 and the recovery fund have also triggered important domestic political changes. In Italy, former president of the European Central Bank (ECB) Mario Draghi is now prime minister and parliament is united behind a €230 billion, multi-year investment and reform package. Seasoned observers might question how long this unity will last, but it stands in stark contrast with the situation shortly after the 2018 election—when two overtly populist parties were setting the agenda.

The Italian economy has struggled since joining the euro, and anything that puts it on a path toward a brighter future represents a step forward, both from a domestic and broader European perspective. However, recent political trends in Germany may be even more significant for the future economic and financial stability of the region.

Germany’s Centre-Right Parties Lose Ground

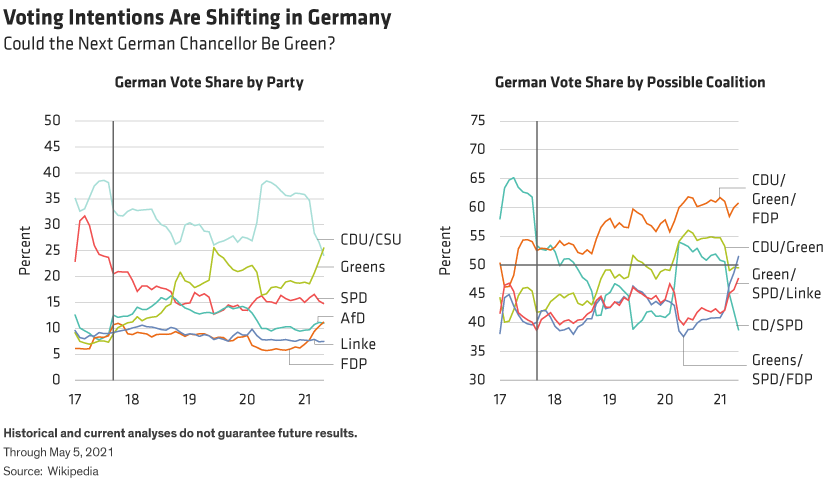

Like many governments, German chancellor Angela Merkel’s CDU/CSU alliance initially gained popularity when COVID-19 struck. But growing doubts over her government’s handling of the crisis and the choice of a lackluster candidate to replace Merkel at September’s federal election have seen support seep away—so much so that the Green Party now leads slightly in opinion polls (Display, below, left pane).

Rise in Green Party Fortunes Favors Deeper EU Integration

While many local pundits think the CDU/CSU will stage a revival before election day, that’s far from certain. At this stage, all we can say for sure is that forming a coalition won’t be easy (Display, right pane) and that the Greens are increasingly likely to be part of the next government. Germany’s next chancellor could even be the Green Party’s co-leader, Annalena Baerbock.

What would a Green government look like? The centerpiece of the party’s manifesto is a 70% reduction in CO2 emissions by 2030 (from a current target of 55%). But markets are more likely to focus on a 10-year, €50 billion annual investment program (1.5% of GDP) financed by higher taxes on income and wealth and a bigger budget deficit, which would require amending Germany’s controversial debt brake.

The Greens also favor deeper European integration and solidarity, partly because this is seen as an essential step toward combatting climate change. Among other things, Green policies would include a larger EU budget and enhanced revenue-raising powers, transforming the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) into a European Monetary Fund and completing the banking union.

Implemented in full, the Greens’ manifesto would represent a significant shot in the arm for European integration and lift some of the burden of supporting weaker euro-area sovereigns from the ECB’s shoulders. The main loser would probably be the German corporate sector, which would be disadvantaged by higher taxes and energy costs.

Of course it’s highly unlikely that, in a coalition government, the Greens would be able to carry out all of their manifesto commitments. Even so, the party’s involvement would almost certainly lead to a looser fiscal stance than would otherwise be the case. It’s still hard to see Germany at the forefront of global fiscal activism, but with greater Green influence at least it wouldn’t be pushing in the opposite direction.

Increased Integration and Stability Support Euro Bond Markets

More fiscal flexibility in Germany could boost euro-area sovereign-bond markets in several ways. For one, there would likely be less resistance by the “frugal” northern European countries to spend more on much-needed structural reforms in Italy. A larger EU balance sheet and subsequent closer fiscal union could also reduce some of the fiscal burden on peripheral euro-area countries.

Also, with the ECB keeping interest rates ultra-low and anchoring front-end yields, and with looser fiscal policy from Green policies, European yield curves would likely steepen further. And higher yields could attract formerly reluctant investors back to peripheral markets.

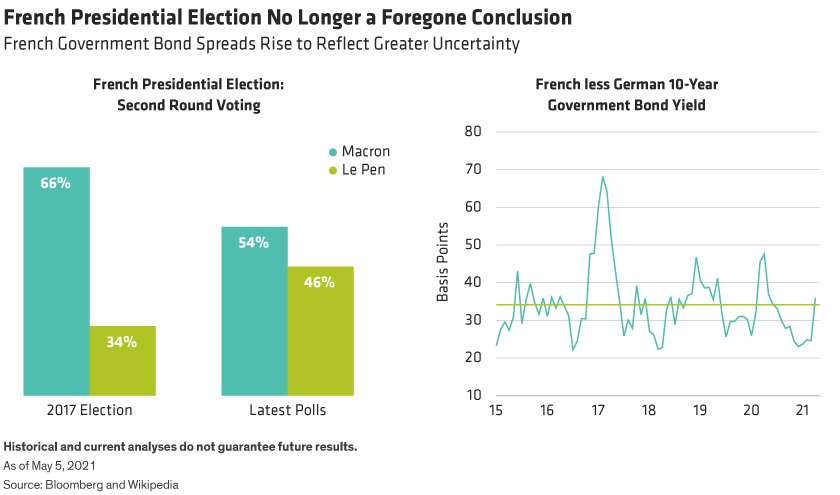

So overall, the near-term political fallout from COVID-19 is surprisingly constructive for peripheral euro-area bond markets. But ongoing ECB bond purchases remain essential for several reasons, not least of which is to maintain control of core bond yields. Things might get trickier when next year’s French presidential election comes into sharper focus—opinion polls point to a much tighter contest between President Emmanuel Macron and Marine Le Pen than we saw in 2017 (Display, below). And there’s the possibility that Italy’s fragile political unity will prove impossible to sustain.

But those are stories for another day. The dominant political driver for European markets between now and September is likely to be Germany’s federal election.

Darren Williams is Director—Global Economic Research at AllianceBernstein (AB).

Nicholas Sanders is Portfolio Manager—Global Multi-Sector at AllianceBernstein (AB).

The value of an investment can go down as well as up and investors may not get back the full amount they invested.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations, do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams and are subject to revision over time.

This post was first published at the official blog of AllianceBernstein..