Addressing technical, idiosyncratic and structural aspects of inflation.

by Carl R. Tannenbaum, Ryan James Boyle and Vaibhav Tandon, Northern Trust

In this Issue:

- Base Effects for Inflation: What Goes Up…

- Supply Chains Are Tangled

- The Impact Of Aging On Inflation

We have all experienced a regrettable moment after we’ve had too much of a good thing. A beachgoer revels in the sun but feels a burn for days; a thirsty runner drinks too much water and is slowed by cramps; happy hour blurs into a full night and begets a difficult morning. Moderation is usually the best course.

Inflation also is best kept at moderate levels. In the months ahead, however, measures of inflation are in for a wild ride, continuing the volatility of so many economic metrics throughout the COVID-19 crisis. But the coming excesses in price level readings are nothing to be alarmed about.

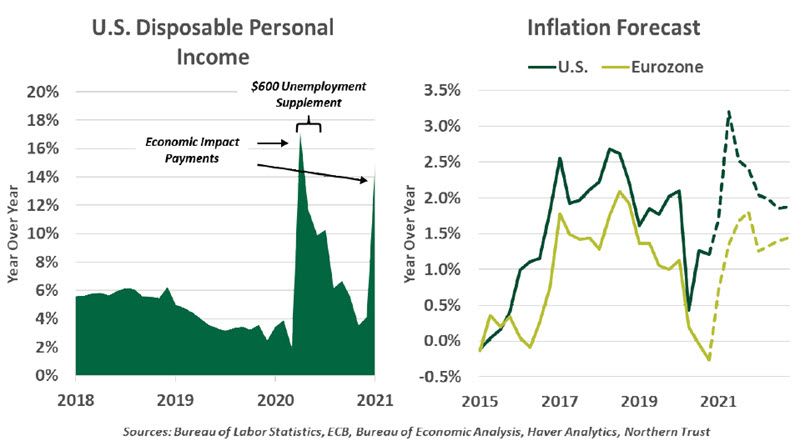

Economic data series have reached new highs and lows over the past year. For example, U.S. personal income experienced wild swings as the CARES Act’s fiscal measures put money directly in consumers’ pockets, then expired. As payments resume and unemployment supplements are renewed, the course of aggregate personal income will continue to look like a roller coaster.

The timing of comparisons is key. While inflation is calculated monthly, it is usually cited in terms of the index value’s change from a year before. That year-over-year measure is going to spike in coming months, as the initial months of the pandemic enter the calculation. (Economists refer to these as “base effects.”) Those months witnessed substantial volatility in the prices of key products, and complications in the process of collecting them.

“The pandemic created a lot of volatility in prices.”

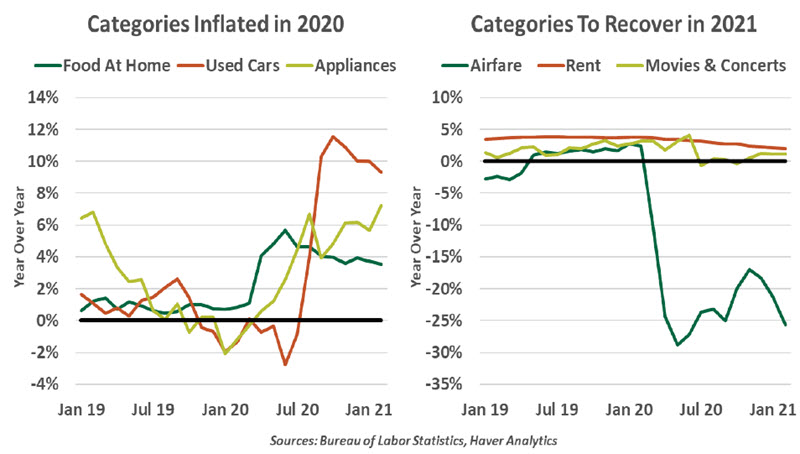

Inflation metrics like the consumer price index (CPI) in the U.S. and harmonized index of consumer prices (HICP) in other countries are measured by surveying a broad array of products and services that consumers purchase. In the past year, several prominent categories have seen disruption:

- Grocery prices increased immediately as consumers stocked up for lockdowns. Even after the greatest fears passed, food prices trended upward as we ate more meals at home.

- Used cars increased in price as consumers sought cost-effective alternatives to public transit.

- Rent levels fell as tenants reconsidered living in urban areas or stepped into homeownership.

- Appliance prices jumped as new home buyers decorated and existing homeowners renovated the homes where they were now spending all their time.

- College tuition, known for rapid price increases in the U.S., moderated as safety concerns, remote learning and immigration restrictions reduced demand.

- The price index for tickets to sporting events went on hiatus in the second half of 2020 as nearly all events were cancelled, leaving no transactions to track.

These trends are expected to prove temporary, and some categories that fell last year are poised for a rebound. Transportation is a prominent one, as airfare prices dropped over 20% and are still down. Car rental and public transit both saw rapid declines in demand but will return as consumers leave their homes. Many restaurants survived with a carryout business, but guest checks will increase as more customers return to dining rooms.

But the recovery to more normal levels will not be a persistent rise, and should not be mistaken for a permanent shift in inflation.

For reasons beyond just the COVID-19 recovery, oil prices are off to a strong start on the year, as producers have not increased production as they have in past growth intervals. Rising energy prices will boost “headline” inflation, especially in emerging markets. But energy prices are unlikely to continue upward at their recent pace. The unpredictability of energy and food prices is the reason policymakers set targets for core inflation, which excludes these categories.

Expected readings of 3% inflation will feel high, but they won’t last long and should not be a reason for worry. Nonetheless, high inflation prints will amplify the anxiety over higher inflation in 2021. Policy responses to the COVID-19 crisis slashed interest rates, gave money to taxpayers and created a surge in the money supply, all of which can contribute to higher prices. Some transient price increases are likely as consumers return to old spending patterns at restaurants, airlines and hotels. But as we have discussed, the conditions that kept inflation in check over recent decades are still in force, and labor market slack will allow most demand surges to be met with more supply.

Markets have digested sudden shifts in inflation before. In 2015 and 2016, for instance, a glut of oil kept inflation rates low in many regions. As prices normalized in 2017 alongside a period of growth in Europe, the euro area saw its year-over-year inflation rate jump from deflation in the first half of 2016 to 2% in February 2017. The increase was foreseeable and well understood, and it did not lead to any sudden changes in policy or expectations.

“Do not be alarmed by high headline rates of inflation in coming months.”

A similar dynamic restrained inflation as the U.S.-China trade war escalated. Tariffs were a new cost that was likely to be passed along in final prices of imported goods. Once they were ingested, though, further price increases were normal. Fortunately, in that case, tariffs were placed on durable goods that represent a small share of consumer spending; though price increases were evident within specific categories of goods, they were too small a share of the basket to move the headline rate of inflation.

High inflation headlines and anecdotes of higher prices in specific sectors over the next few months should be taken in stride. Some are calling for a more aggressive policy response if inflation surges in the middle of the year, but those appeals are premature. Best to keep a cool head if things heat up this summer—and drink plenty of water.

The pandemic has visibly restricted consumers’ options for spending money on services like restaurants and leisure. Instead, our COVID-19 lifestyles have shifted our consumption toward buying goods.

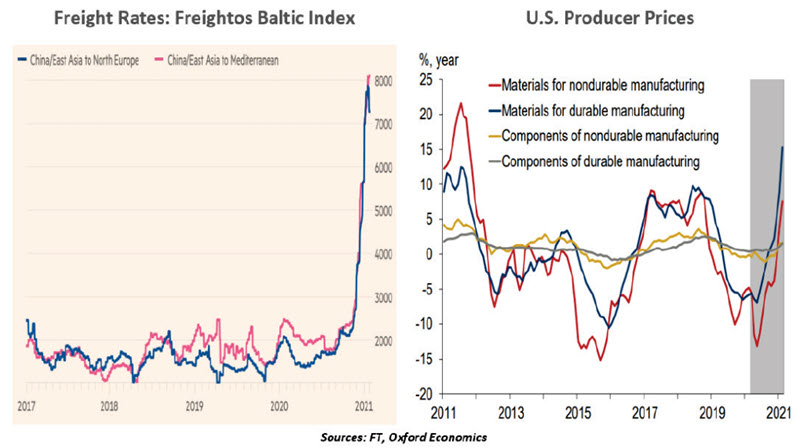

Demand for electronics, furniture, cars and other manufactured goods has risen. Most of these goods are imported from the east into the western hemisphere, after having travelled the world’s oceans on container ships. COVID-19-induced disruptions and increased spending on consumer goods has put global supply chains under stress.

Manufacturers spent decades optimizing supply chains to reduce costs and are now finding themselves stretched. Sudden events like the February freeze in Texas shut down chemical plants, limiting supplies of plastics and other intermediate materials. A recent fire in Japan at one of the world’s leading chip makers will only add to the troubles of auto manufacturers who have had to slash production because of a semiconductor shortage. Computers, electronics, chemicals and metals are also among the affected sectors.

Apart from delays owing to short-term shortages of parts and materials, container shortages have hit supply chains. A dearth of empty shipping containers in Asia and bottlenecks at the U.K.'s seaports are key factors behind the problem. Many factories closed temporarily because of staffing shortages in the U.S. and Europe, leading to large numbers of containers sitting at ports. The ports themselves are operating at less than full capacity because of measures intended to slow the spread of COVID-19.

Trade tensions have also played their part. Some firms and industries have tried to diversify supply chains away from China, but perfecting logistics around the new facilities is easier said than done. In the U.K., the difficulties have been compounded by post-Brexit non-tariff barriers in trade with the European Union.

This combination of factors has produced a surge in shipping costs. According to shipping broker Harper Petersen, global shipping costs are up 80% since the pandemic started. Another indicator, the Baltic Dry Index, a composite measure of the rates charged by shipping lines to move dry goods, is up 128% in a year, with a 60% increase since early December. The cost to send a container from East Asia to the U.S. west coast has increased from $1,500 to $4,000 since the start of 2020. While the trend has been a boon for the major shipping lines, which have seen their profit margins widen, it is generating pipeline price pressures.

“The pandemic has strained the chains that deliver goods.”

Producer prices are firming. China’s exporters and European retailers have been hit by shortages and rising costs. In fact, manufacturers in Europe appear to have already started passing on rising costs as margins take a further beating. Retailers are coming under increased pressure to distribute some of this burden to consumers; unfortunately for them, they lack pricing power.

Supply-side disruptions amid rising container shipping costs is only adding fuel to worries about inflation. But many observers, including ourselves, aren’t overly concerned. Central bank commentary has differentiated between transient and persistent inflation, and freight costs are unlikely to hold at their current levels. In the long run, pressure to decarbonize could change the economics of the industry, but it is not a concern yet.

The cost-push inflationary pressures emanating from shipping costs are largely a result of the pandemic, and can be expected to dissipate over the next few quarters after the virus is tamed. More widespread vaccinations and reopening will also drive consumers back towards the services sector, diverting significant traffic away from cargo ports and into airports. All of this should help take the kinks out of global supply chains.

The most prominent economic theme during the first quarter of the year has been rising inflation risk. Some increases in measured inflation are certainly likely through the middle of 2021, but we do not think that they are likely to persist (see earlier article).

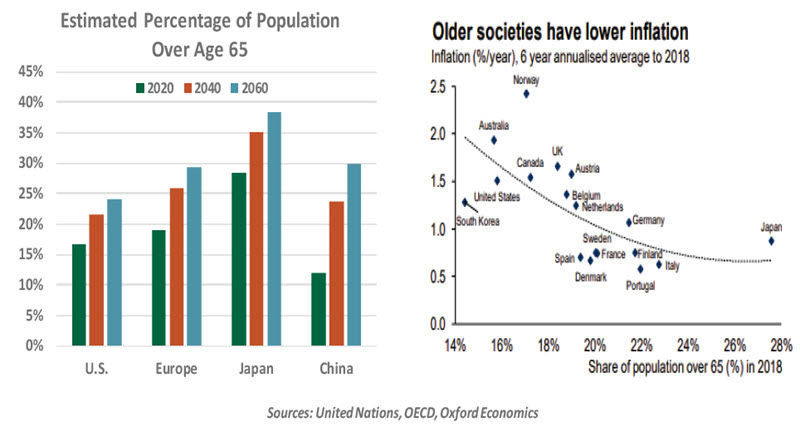

Over the longer term, some are concerned that aging societies around the world will add to the inflation rate. As workers retire, growth in the labor force will slow; this has the potential to increase wages and prices. This prospective sequence of events was illustrated at length in last year’s book from Charles Goodhart and Manoj Pradhan, building on research they had done for the Bank for International Settlements.

It is certainly true that the world is aging, with some of the world’s biggest labor suppliers (China, in particular) getting collectively older at a rapid rate. But the economic literature generally finds that more elderly populations are associated with lower rates of inflation. The reasons for this aren’t difficult to comprehend:

- Once retired and living on fixed incomes and accumulated savings, citizens become more frugal. With life expectancy expanding steadily (at least it was prior to the pandemic), households must make their resources last for longer periods. With longevity uncertain, consumption patterns become conservative and bargain hunting intensifies.

- Inflation diminishes the value of saving, so older populations tend to favor politicians and policymakers who will manage inflation closely.

“Retired workers become more frugal, limiting inflation.”

In the decades ahead, it is certainly true that labor force growth will be on a lower trajectory in many countries. But there are also young emerging markets that may be in a position to take a more active role in global supply chains. Further, tight labor markets have not produced higher wage growth in the recent past; technology has helped to keep output growing even as the post-WWII generation has begun its transition into retirement. That trend will likely persist.

There are those that fear getting older, because it can introduce limitations. But aging will also likely limit inflation—and that’s a good thing.

Yields have risen suddenly, but they are now approaching levels seen just before the pandemic hit the world. We do not foresee rising interest rates as a meaningful threat to building economic momentum.

Information is not intended to be and should not be construed as an offer, solicitation or recommendation with respect to any transaction and should not be treated as legal advice, investment advice or tax advice. Under no circumstances should you rely upon this information as a substitute for obtaining specific legal or tax advice from your own professional legal or tax advisors. Information is subject to change based on market or other conditions and is not intended to influence your investment decisions.

© 2021 Northern Trust Corporation. Head Office: 50 South La Salle Street, Chicago, Illinois 60603 U.S.A. Incorporated with limited liability in the U.S. Products and services provided by subsidiaries of Northern Trust Corporation may vary in different markets and are offered in accordance with local regulation. For legal and regulatory information about individual market offices, visit northerntrust.com/disclosures.

Copyright © Northern Trust