Will the Fed respond to inflation concerns?

by Carl R. Tannenbaum, Ryan James Boyle and Vaibhav Tandon, Northern Trust

In this Issue:

- Bird Watching At The Federal Reserve

- The Changing Face(s) Of The FOMC

- China Has Plans

My life B.C. (before COVID-19) included frequent barbecues. As I was preparing the grill one afternoon, I noticed something streaking across the sky toward the backyard. It was a hawk; in the blink of an eye, it scooped up an unsuspecting critter and disappeared almost as quickly as it had arrived. After that, I was especially careful to protect the sausages we were going to enjoy for dinner.

Hawks are aggressive birds of prey. Doves, by contrast, are docile vegetarians. The depiction of doves as signs of peace dates from biblical times (one carried an olive branch to Noah); the use of the term “hawk” to describe someone who is more forceful dates from the late 18th century.

In more recent times, the contrast between the two fowl has been employed to describe the inclinations of central bankers. When inflation was raging at a double digit pace in the late 1970s, monetary “hawks” favored aggressive measures to tame it. “Doves,” by contrast, were more likely to favor an easy policy that would support economic growth and employment.

The U.S. Federal Reserve meets next week to discuss monetary policy. The extremely accommodative stance taken recently has led some to call this the most dovish Fed in decades. (And as the following article suggests, it may become even more dovish over the next year.) Its willingness to keep the spigots fully open is alarming some, but cheering others.

A bit of background is in order. While most of the world’s central banks seek to manage inflation, the Fed is the only one also tasked with pursuing maximum employment. Traditional thinking has held that the two elements of this “dual mandate” aren’t easy to reconcile: at times, it is hard to achieve one without retreating on the other.

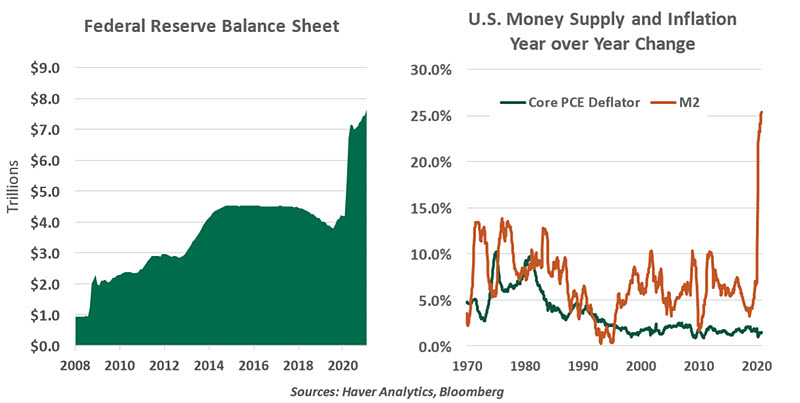

But this “Phillips Curve” mode of thinking has not held up well in recent years, as the United States has simultaneously experienced low inflation and low unemployment. Further, the notion that inflation is everywhere and always a monetary phenomenon has also come under question as the linkage between money supply growth and changes in the price level has weakened. Two central tenets that have informed Fed policy for decades are no longer as helpful.

Of course, the pandemic is testing all kinds of economic identities, leaving policymakers little to go on. The sudden shifts in fortune, and the magnitude of government efforts aimed at stabilizing conditions, have been unprecedented. Central banks around the world have facilitated the relief efforts by purchasing immense volumes of government bonds and promising to keep interest rate levels low. The collaboration with fiscal authorities, while entirely necessary, has raised concerns about central bank independence; the Fed now owns $4.8 trillion of Treasury securities, more than 20% of the total held outside of the government.

“The prospect of a “summer surge” has investors worried about inflation.”

The Fed sets its policy on the basis of forecasts, which have been especially difficult to compose over the past year. (Some have likened the effort to steering a vehicle whose windshield is covered in dust.) The Fed’s latest projections will be released at the conclusion of its meeting next Wednesday afternoon, and they are sure to be upgraded from December’s edition. A “summer surge” is coming, as advancing vaccination combines with fiscal stimulus and pent-up saving and demand. Growth and employment are likely to increase sharply in the second and third quarters of this year.

The potential for the surge to stress capacity has prompted fears of reflation. Inflation expectations are at their highest since 2014, and long-term interest rates are up sharply since the start of the year. For the first time in a long while, inflation hawks have been seen on the horizon, pressing the Fed to pledge allegiance to price fighting and to signal some limit to its largesse.

Thus far, Fed officials have not responded to those challenges. Collectively, they do not see much risk that inflation will escape containment (and neither do we, as we discussed here). Fed speakers have noted that fighting an inflation phantom would diminish employment gains, especially for communities that have struggled to secure them. The pandemic has been especially hard on certain sectors of society, and the Fed seems committed to improving their prospects.

As stated in the Fed’s mandate, the quest for maximum employment is complicated by the difficulty in defining what the term means. The overall unemployment rate is an incomplete guide, as it excludes discouraged workers who have left the labor force and those who are underutilized; it can also mask differences in progress between communities.

Several years ago, former Fed chair Janet Yellen proposed a dashboard of measures to assess progress towards full employment. Current chair Jay Powell has taken the concept a step further by stating that “maximum employment is a broad and inclusive goal.” He has suggested the Fed will be focusing on raising the fortunes of the less fortunate, and will not begin considering pulling back until this objective has been achieved.

“Expect the Fed to be hawkish in its pursuit of broad employment objectives.”

The past several recessions have seen very slow recoveries in the labor market. The nature of the pandemic recession is a bit different; a durable reopening of the economy this summer should bring scores of workers back into the labor market and allow those working part time to resume full-time work. But it is unlikely that employment rates will come anywhere close to their January levels for a long time. The Fed is intent on accelerating this process, and feels strongly its objective can be achieved without pushing inflation out of bounds.

The Fed’s effort to restore full employment can hardly be called passive. The tone of statements from Fed officials and the scale of their interventions suggests drive and conviction. They are hawkish…but not in the same way they were 40 years ago. And this change of orientation is ruffling some feathers.

When Doves Vote

Describing the Fed as institutionally hawkish or dovish gives too little credit to decisions made by a committee of individual thinkers. The people filling the seats at the table of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors determine the board’s overall inclination.

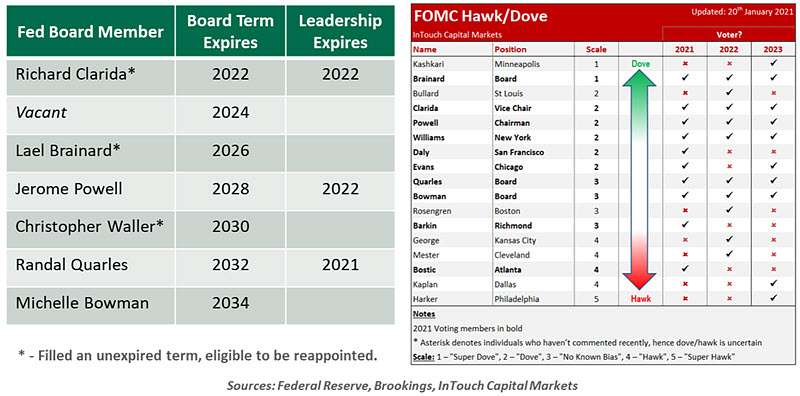

The seven members of the Board are appointed by the U.S. president to serve staggered 14-year terms. Fourteen years is a long run. It has become the norm for governors to resign before their terms expire. The leadership roles within the board (the chair and two vice chairs) are four-year appointments, also nominated by the president.

This structure was intended to keep the Fed apolitical. Governors can hold their positions well past the president who appointed them. With 12 voting members, any one appointee cannot sway the full board. However, a series of appointments over a short time span could cause a realignment of the Fed’s persuasions.

Fed appointments have not yet been a priority for the Biden administration, but they will need the president’s attention soon. Currently, one board seat sits vacant. Then, in a one-year window, all three chair terms will expire: Vice Chair for Supervision Randal Quarles in October 2021, Vice Chair Richard Clarida in September 2022, and crucially, Chair Powell in February 2022. Though they could continue as regular board members, many former leaders have found the end of a leadership term to be a natural time to resign. Biden will have one immediate and potentially four total vacancies to fill in his first two years, along with a total change to leadership. This gives him a unique opportunity to shift the alignment of the board.

“The Fed’s voting members support very accommodative monetary policy.”

Current governor Lael Brainard was a rumored candidate for Secretary of the Treasury, a role that went to former Fed chair Janet Yellen. Brainard’s history of dissenting from board decisions to loosen regulation may align well with Biden’s priorities to increase the role of financial regulation, especially regarding climate matters. She is certainly in line for a leadership role at the Fed.

Voting membership of the Federal Open Market Committee rotates annually. The presidents of the regional reserve banks (excluding New York’s permanent vote) take one-year turns as voting members. The regional presidents known to be most hawkish will not regain votes until 2023.

During the crisis, board members have done an admirable job of putting the crisis and recovery ahead of their prior beliefs. They now face the challenge of plotting a return to normalcy. The coming turnover of the Fed board will allow the Biden administration to strengthen its alignment with the administration’s goals.

Goals

China’s top leadership recently concluded its most important political gathering of the year, the Two Sessions meetings, which outlined the country’s economic and policy agendas.

After shelving its economic growth target last year for the first time in decades, China decided to return to it in its plan for 2021. Beijing has set a vague objective of “above 6%” growth this year. The phrasing will lower its incentive to inflate stimulus or output data at provincial levels. In the long run, reduced artifice in reporting will be beneficial for the economy.

Beijing is seeking to cut back its fiscal support for the economy. It has given emphasis to reducing its debt burden as well, which grew by a whopping 30% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020. (By comparison, the U.S. has approved aid of almost 25% of GDP to fight the pandemic.) The central government’s budget deficit-to-GDP target has been set at 3.2%, compared to 3.6% last year. The special purpose bond issuance quota for local governments has been scaled back slightly to RMB 3.65 trillion ($564 billion) from RMB 3.75 trillion last year. Beijing, as the first major economy to emerge from economic shocks of COVID-19, will not be issuing additional COVID-19 bonds this year after having sold over $150 billion in 2020 for pandemic relief efforts.

Though focusing on normalizing monetary policy and debt reduction bodes well for China’s long-term economic health, it presents a near-term risk. China entered the pandemic with high levels of credit risk. Close to 40 Chinese companies defaulted on nearly $30 billion of bonds (domestic and offshore) last year, up 14% from 2019. That number is only going to rise as policy tightens with renewed emphasis on deleveraging. Bond market observers will recall the deleveraging of 2017, which sent Chinese corporate and government bond yields to multi-year highs before reversing course in 2018 as the U.S-China trade war took hold.

The policies adopted last week will also carry external implications. China intends to “close loopholes” in the Hong Kong electoral system to prevent foreign interference. This will further aggravate external concerns over Hong Kong’s status as one of the world’s leading financial centers and trade hubs.

“China’s economic actions have often fluctuated from its commitments.”

Beijing is also seeking to reduce dependence on foreign technology and increase competitiveness with the United States. Policymakers are aiming to give larger focus to high-tech industries such as robotics, artificial intelligence and quantum computing, along with the rare earth materials that are essential to circuitry. For these purposes, China is set to boost research and development spending by 7% annually to bring total spending to $580 billion by 2025, compared to about $550 billion spent by the U.S. in 2018.

China is the world’s largest polluter, and actions speak louder than words. While Two Sessions included a lofty blueprint to become carbon neutral by 2060, the announcement came on the same day a new $10 billion coal project was approved. The European Union, the U.K., Japan and about 70 other nations have set emission plans for 2030 under the Paris Agreement. China has not yet unveiled its plan to meet its Paris commitments.

Transitioning to new growth drivers will be the most daunting task for the Chinese economy. China is gradually losing its demographic dividend due to its aging population, and the economy relies heavily on labor- and energy-intensive industries for growth. As technology and climate change bear down on China, engineering a transition to a new lower-carbon economic model is going to be a tough job. The plans set out at the Two Sessions conclave are noble aims, but more sessions will certainly be needed to ensure that they are met.

Information is not intended to be and should not be construed as an offer, solicitation or recommendation with respect to any transaction and should not be treated as legal advice, investment advice or tax advice. Under no circumstances should you rely upon this information as a substitute for obtaining specific legal or tax advice from your own professional legal or tax advisors. Information is subject to change based on market or other conditions and is not intended to influence your investment decisions.

© 2021 Northern Trust Corporation. Head Office: 50 South La Salle Street, Chicago, Illinois 60603 U.S.A. Incorporated with limited liability in the U.S. Products and services provided by subsidiaries of Northern Trust Corporation may vary in different markets and are offered in accordance with local regulation. For legal and regulatory information about individual market offices, visit northerntrust.com/disclosures.