Brexit negotiations had another unproductive week. Parcel shipping volumes are breaking records. And when and why might the Fed alter its asset purchases?

by Carl R. Tannenbaum, Ryan James Boyle and Vaibhav Tandon, Northern Trust

Summary

- Brexit: Down To The Wire Again

- This Holiday Season: Failing to Deliver

- The Fed Assesses Asset Purchases

In 1918, the world witnessed the end of World War I, but it was not the end of the world’s problems. The lingering Spanish Flu pandemic curtailed celebrations of peace.

This week, the U.K. became the first major Western economy to roll out a COVID-19 vaccine to the masses. Inoculation, according to British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, is a “tremendous shot in the arm for the entire nation.” Unfortunately, there a real possibility that Britain will have to temper its vaccination celebration. Failure to secure a Brexit deal with the EU would deliver another, less happy jab.

Negotiations between the U.K. and European Union (EU) on a post-Brexit trade deal are running out of time as the December 31 deadline approaches. Brexit couldn’t even feature in this week’s two-day EU summit as its leaders were busy seeking a plan to unlock the regional budget, which includes critically-needed economic stimulus.

Roadblocks to a Brexit agreement are limited in number, but stubbornly persistent. The ability of Britain to support its national champions is one of them. When a state backs its domestic providers, it creates an unlevel playing field. Its trading partners might justifiably use tariffs to even things up.

The U.K. nonetheless wants a guarantee of tariff-free commerce with the EU, which the Europeans have pushed back against. The British side has noted it has been much less prone to using state aid than have other European nations.

Fisheries are also contentious. The United Kingdom wants a big increase in its fishing rights based on the location of fish; Europe is insisting on continuing the current system, in which its fishermen enjoy a much larger share of fish quotas in British waters.

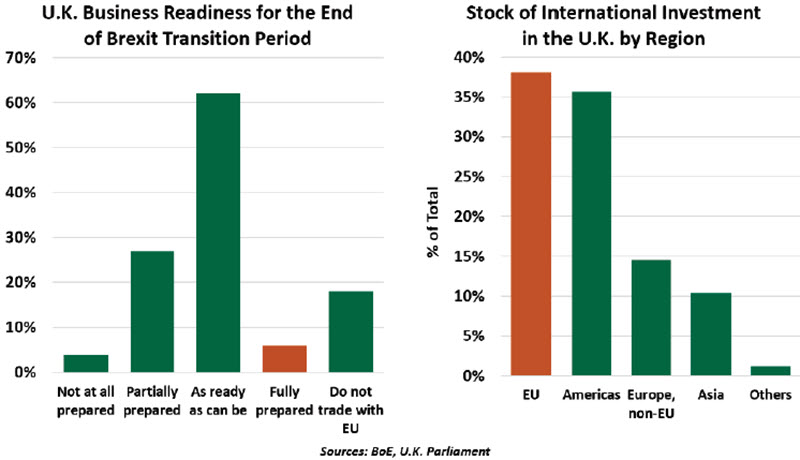

With the U.K. and key EU member states suffering more from COVID-19 than other advanced economies, a deal is in the political and economic interests of all parties. While the U.K. government claims advances have been made in its preparation for Brexit, businesses still don’t have clarity on how the borders will operate after January 1. A November Bank of England survey of chief financial officers showed that only 6% of them were fully prepared for the end of the transition period.

“Businesses aren’t fully prepared for a Brexit deal, let alone the risk of a no-deal Brexit.”

Decades of progress toward free movement of goods, services, people and capital will be affected if the U.K. leaves the European single market and customs union without a deal. Neither side wants a cliff-edge scenario: the European Commission’s contingency plan offers air and road connectivity to the United Kingdom for a limited time into the new year. The U.K., too, will delay full checks for goods arriving from the EU until July 1, 2021.

A trade deal might remove the need for tariffs (or taxes) to be paid on goods crossing borders, but goods entering the EU from Great Britain will face large amounts of paperwork and checks, including customs declarations, rules of origin checks, product safety certificates and food inspections. Importers and exporters are not likely prepared for the new procedures.

The stakes are particularly high for the U.K., as the pandemic has put the economy on course for its deepest contraction in more than three centuries. More than 40% of British exports reach the EU annually, and the bloc is the source of half of its imports. The EU has also been accounting for about 40% of foreign direct investment (FDI) into Britain. FDI flows between the two sides have already suffered since the Brexit referendum in 2016.

Financial services and export-dependent sectors like automobiles, farming and textiles would be among the hardest hit. About 85% of foods imported from the EU would attract tariffs of 5%. The farming industry, which accounts for two-thirds of British exports to the EU, would face considerably higher tariffs. British automakers would face a 10% tariff on all auto exports to the EU.

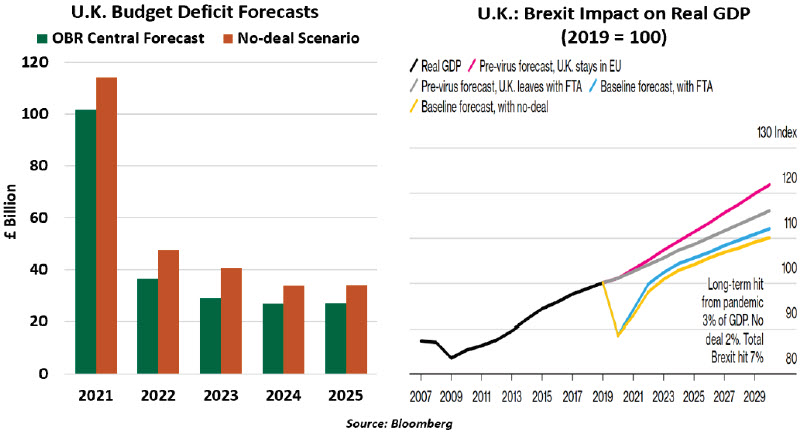

Regardless of the outcome, the U.K.’s economy will likely be smaller than what it would have been without Brexit. According to the Office for Budget Responsibility, a free trade agreement (FTA) with the EU would lower gross domestic product (GDP) by 4% through 2030. Reverting to the World Trade Organization (WTO) rules would raise the loss to 7%, according to Bloomberg. The loss of economic output would inflict further fiscal damage, leading to either tax hikes or spending cuts. Coming on the heels of the pandemic, this would be very damaging to the British economy.

The U.K. would not be alone in its misery. Ireland, significantly dependent on the U.K. for trade, is highly exposed to a no-deal outcome, economically and politically. According to a European Central Bank paper, a messy no-deal Brexit could cost Ireland 6% of long-term output.

A messy Brexit would inflict serious economic pain on major European economies too. Though the direct hit will be less damaging to EU GDP than the U.K., a no-deal Brexit would bring tariffs on €512 billion ($621 billion) of annual product flows along with potential delays from customs checks. Germany’s auto sector, along with France’s fishing, wine and food sectors, will likely be among the worst affected.

“A no-deal Brexit will bring significant pain on EU nations, too.”

The U.K.’s recent decision to withdraw the controversial clauses in its Internal Market Bill, which gave ministers the power to unilaterally override the Brexit divorce treaty, along with the fact that both sides are still engaged in Brussels, gives us some hope for a thin FTA before the deadline. But each day that goes by leaves less time for ratification and preparation.

While the world looks forward to defeating the pandemic, Britain could well end up exposing itself to another affliction. In the coming days, negotiators must find a way to secure Europe’s long-term economic health.

Parcel Problems

Working remotely has brought me closer to the rhythms and crescendos of the household. Tuesdays at 10 a.m., the house gets vacuumed. Thursdays at 3, my wife holds a raucous video call with our two nieces. And every morning at 9, my wife sings the soundtrack of “Hamilton” at the top of her lungs while exercising on the treadmill. I have to be careful not to schedule critical work consultations during those noisy intervals.

Another cadence I’ve become accustomed to is the frequent rings of the doorbell as packages arrive. The chimes are getting a workout this month, as holiday parcel volume combines with expanded pandemic-driven delivery of essentials. Stacks of boxes have rendered our entryway almost impassable. (That’s not such a hardship, as we aren’t getting many visitors these days.)

Our experience is not unique. The pandemic has created a parcel frenzy this holiday season. E-commerce volumes have soared this year, accelerating the transition away from brick-and-mortar retailing. The surge has challenged shipping, fulfillment and delivery to the point where targeted arrival dates have become difficult to maintain. For many families, the exchange of Christmas gifts will not be complete until well into January.

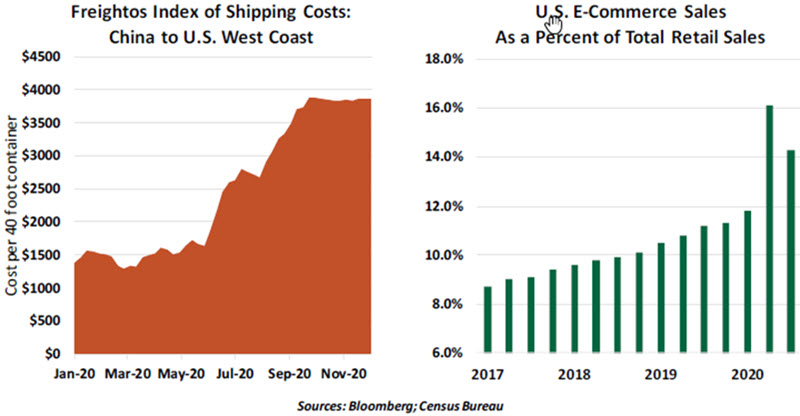

When COVID-19 first surged, lockdowns threw supply chains into disarray. As we discussed last June, output in China ceased, and then surged. But procedures at ports and intermodal facilities had to be altered to respect social distancing. As a result, timelines for inspecting and transitioning containers lengthened, and the fraction of container ships arriving on time plunged.

With containers moving more slowly, a shortage of available containers developed. Reserving space to ship goods became difficult and expensive. More than a quarter of the world’s air fleet remains parked, so goods that would normally be transported in the belly of commercial aircraft have to use other channels.

Once containers arrive by water or air, their overland progress is limited by shortages of truck drivers, whose numbers are down by about 5% since the summer. Some smaller carriers ceased operation after government support programs wore off. Some drivers have been hesitant to sustain their routes as COVID-19 spread across the country.

In addition to supply chain bottlenecks, demand has stressed capacity in the system. Thanks to public health gains and fiscal stimulus, activity rebounded more robustly than expected in the third quarter, catching logistics providers by surprise. With service categories like travel restricted, many families have increased their spending on goods this year. An increasing fraction of that spending has come through e-commerce. The long-running trend has gotten a huge boost during the pandemic, with shoppers appreciating the ease and relative safety of online purchases.

“Logistics have not recovered nearly as quickly as consumption has.”

To respond to the change in channels, shippers had to route more goods to fulfillment centers instead of retail outlets. The labor force supporting the process also had to shift; the warehouse and transportation sectors have been among the strongest job creators in the past several months. Some providers had the foresight to move early, to be ready for the surge. (Amazon started developing its own logistic capacity some years ago, reducing its reliance on outside carriers.)

Others, however, have been caught off guard: at the beginning of December, UPS began to limit the number of parcels it would collect from some major chains; smaller merchants are also facing caps. The holiday season accounts for a large fraction of yearly revenues and profits for retailers, so any constriction of sales and margins at this time of the year is particularly painful.

The world of logistics is highly sophisticated. Prior to the pandemic, goods moved so seamlessly that we rarely gave the system much thought. But like so many other things this year, the stress introduced by COVID-19 has caused cracks that will be difficult to repair. I just hope that the late arrival of my wife’s Christmas present does not create a crack in our relationship.

Going Long

Next week, the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) will have its last meeting of a busy year. Among many outcomes, we will look for guidance on the Fed’s asset purchase program.

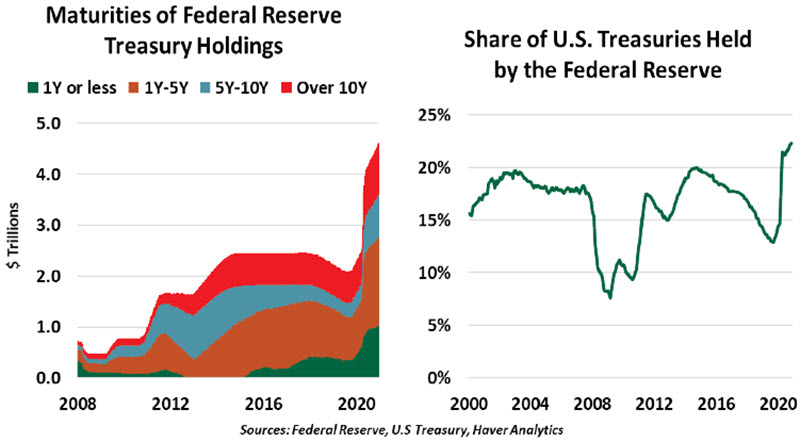

The global financial crisis paved the way for central banks to support their economies by buying government debt. These asset purchases support government spending and help to keep yields low. The Fed was already buying assets at a moderate pace prior to the pandemic, but escalated monthly purchases to $120 billion starting in March. Those purchases were an essential component of the Fed’s efforts to restore liquidity to markets.

The Fed has a choice of what bonds to purchase. Accumulating short-term instruments helps keep rates down for variable rate loans such as those used by firms for working capital. Buying long-term bonds can hold down mortgage rates, helping the housing industry.

To date, additions to the Fed’s balance sheet have been concentrated on the short end of the U.S. Treasury curve. At the start of the year, only 5% of the Fed’s Treasury portfolio was in bills of up to 90 days maturity; today, that share has increased to 8.5%. Meanwhile, the Fed’s allocation to Treasury bonds (longer than 10 years) has fallen from 27.5% to 22.4%.

“With yields already low, asset purchases lose their power to add stimulus.”

In recent weeks, long-term Treasury yields have drifted upwards as the prospect of a post-pandemic economic surge raises concerns of increasing inflation among some investors. This might tempt the Fed to shift its purchases to help sustain the strength in residential real estate, one of the brightest spots in the U.S. economy at the moment.

A potential downside of lengthening maturities is that they might make it more difficult for the Fed to reduce its balance sheet if and when conditions warrant. That decision point is likely some way into the future, though, and the Fed still has large concentrations of short-term instruments that could facilitate any recalibration.

Background supporting its decision will be found in the Fed’s quarterly Summary of Economic Projections. Economic news since the September edition has been notably positive; if Fed officials raise their growth outlooks or projections of inflation, they may prefer not to make large changes to their portfolio. Given the massive changes made to monetary policy this year, the Fed could be forgiven for standing pat this time around.