by Eric Winograd, Senior Economist, AllianceBernstein

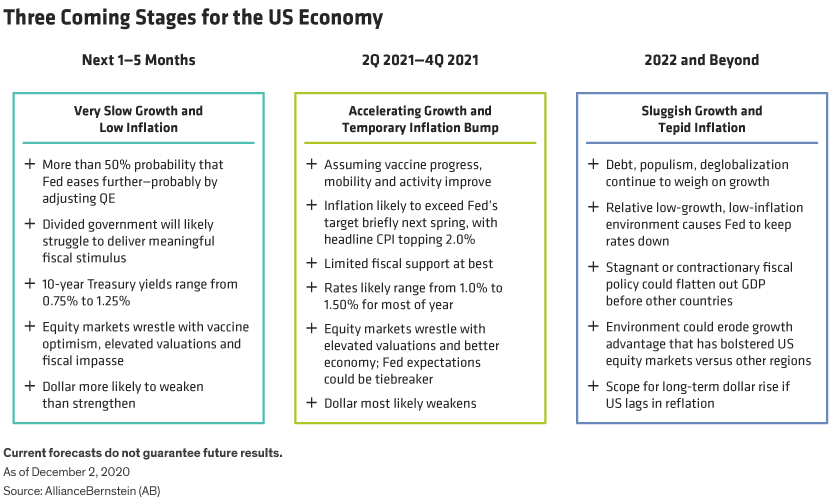

For the first time since the COVID-19 outbreak, the basic contours of the US economic trajectory are in clearer focus, giving us more confidence in sketching out three coming stages that collectively take us from near term to long term (Display).

Near Term (1–5 Months): Very Slow Growth and Low Inflation

The coronavirus is likely to accelerate throughout the holidays, with activity restrictions likely to tamp down growth—even without another round of broad national lockdowns. We don’t expect a contraction as we do in Europe, but risks point in that direction. At the very least, slow growth and low inflation is likely for the next several months. A vaccine tomorrow won’t put many people back to work today.

Accommodative monetary policy and stagnant fiscal policy. The Fed will keep monetary policy easy for the foreseeable future. We see a greater than 50% likelihood that it will ease further near term, most likely by recalibrating its quantitative easing (QE) purchases to hold down longer-term interest rates. We think there’s a good chance this will happen in the first quarter of 2021.

The Fed may feel compelled to act because fiscal policy is unlikely to pick up the slack. A divided Washington, DC, will likely struggle to deliver fiscal stimulus, and if it does succeed, the package will, at best, probably offset some of the economic damage from the winter—not boost growth.

Low interest rates. Given the bleak environment, the Fed simply won’t let rates rise meaningfully. We expect 10-year Treasury yields to range from 0.75% to 1.25%. Equity markets will wrestle with balancing vaccine optimism and sparse investment alternatives against elevated valuations and a fiscal impasse. The dollar is more likely to weaken than strengthen; it’s a bit expensive by most metrics, and the market will likely look ahead to the next regime, which is likely to be dollar negative.

Medium Term (2Q 2021–4Q 2021): Accelerating Growth, Temporary Inflation Bump

Assuming effective vaccines become more widely available during 2021, the most-distressed industries can begin to open in the second quarter and see resurgent activity over the summer, as people begin to travel, attend in-person recreational events and do the things they couldn’t do for most of 2020. It won’t quite be an all clear, but we should see a boost to growth as mobility improves.

As growth increases, inflation is likely to exceed the Fed’s target temporarily next spring, as sharp price declines from earlier 2020 drop from the year-over-year calculation. The underlying inflation rate will still likely be below target, but headline consumer price inflation numbers will top 2.0% in mid-2021 before falling off again.

Accommodative monetary policy, contractionary fiscal policy. The Fed won’t just soften the blow from COVID-19 and then go back to “normal.” It was worried about the outlook before the pandemic, and a reopening rebound won’t change that. The Fed may not ease more, given its limited tool kit, but don’t look for any tightening either. We expect the central bank to articulate its eventual QE exit, but that move won’t happen until late 2021 at the earliest—with 2022 a more likely time frame.

Higher inflation expectations (which the Fed wants) could speed that timetable. We think fiscal policy would move the needle there, but if Congress won’t pass meaningful stimulus in a bad economy it’s not likely to do so in a strengthening one. Our outlook is for limited fiscal support at best, so the fiscal impulse for next year is very likely to be contractionary.

Low interest rates and a weaker dollar. If growth accelerates as we expect, the Fed will be more amenable to rising rates than in a weakening economy, so we see the scope for higher rates expanding during 2021. However, with the Fed worried about the long term and still using QE to keep policy accommodative, rates are likely to stay within a range of 1.0% to 1.50% for most of next year.

Equity markets will continue to wrestle with elevated valuations and an improved economy, with Fed expectations potentially acting as the tie breaker. If investors start worrying about tighter monetary policy, a headwind will develop. The dollar will most likely weaken over the medium term; for a few months, this will look like proper reflation.

Long Term (2022 and Beyond): Sluggish Growth, Tepid Inflation

All of the factors that argued for lower growth pre-COVID-19—including high debt, populism and deglobalization, remain—most of them accelerated by the pandemic. These trends will weigh on growth over the long run, as they have for most of the past decade. Nominal GDP growth barely averaged 4% in the five years before the pandemic; that level or even a bit lower seems likely on the other side.

Impotent monetary policy, fiscal policy as the key. In the long run, the Fed can’t generate sustainable inflation on its own, making fiscal policy the key variable. Both monetary and fiscal policy must be in sync—”joined at the hip,” as we call it—to push up growth and inflation sustainably. The Fed has opened the door, and incoming Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen would be happy to walk through it with a sizable fiscal boost. But Congress controls fiscal policy, and the expected political balance makes this unlikely.

Historically, when central banks monetize debt—as the Fed is essentially doing—inflation rises. But that’s because fiscal authorities have taken advantage of that monetization by spending. If the US can manage to do that, it could break out of its rut and into a different regime. If not, the Fed won’t generate the higher inflation it’s targeting. It all comes down to fiscal politics.

Low interest rates, potential loss of economic growth advantage. As long as the US is in the expected low-growth, low-inflation regime, the Fed will keep rates very low, limiting the potential rise in market-driven rates. This isn’t to say that 10-year Treasuries will always yield below 1%, but a return to something on the order of 2.5% or 3.0% isn’t likely for the foreseeable future.

The US, with stagnant or even contractionary fiscal policy, would be almost alone among major economies. This position would make its nominal GDP likely to flatten out sooner—and less likely to move meaningfully higher over any forecast horizon. An environment like this could erode the growth advantage that has bolstered US equity markets at the expense of other regions. It would also suggest scope for long-term dollar appreciation if the US is left behind while the rest of the world works toward reflation.

Eric Winograd is a Senior Economist at AllianceBernstein (AB).

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations and do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams. Views are subject to change over time.

This post was first published at the official blog of AllianceBernstein..