by Sonal Desai, Ph.D., David Gilbert, and Scott Glasser, Franklin Templeton Investments

As economies reopen from COVID-19 lockdowns, there have been fundamental shifts to daily life and work, as well as the investment landscape. Sonal Desai, Chief Investment Officer, Franklin Templeton Fixed Income, Scott Glasser, Chief Investment Officer of ClearBridge Investments, and Dave Gilbert, Chief Investment Officer of Clarion Partners, discuss the changes they are seeing.

Check out our latest “Talking Markets” podcast for a discussion hosted by Katie Klingensmith.

Transcript

Katie Klingensmith: Thank you all for joining us. Let’s start out with Dr. Sonal Desai and a Franklin Templeton–Gallup study analysing the course of economic recovery from COVID-19 in the US. Sonal, tell us about this study and some of its key initial findings.

Sonal Desai: Thanks Katie. We launched a survey—the first of its kind really in terms of scale—with Gallup to try and understand how consumers were in fact thinking about their behaviours. This is a survey, which, it’s a pulse, so it happens every single month for the period of six months. And we’ve got some pretty interesting results already. What we found was that over the first couple of months as, we, of course saw consumer confidence in their desire to participate in the economy, it collapsed in the first couple of months of COVID. Then we had a series of reopenings, it started picking up again. And then of course, we got whatever you want to call it—continuation, the second wave—we got that happening over the course of July and August. And so we were very curious and concerned about whether we would see consumers desire to take part in the economy collapse again. And instead what we saw was it actually stabilised. People have increased their level of saving. There’s absolutely no doubt about it. And I think one concern we have about people having increased their savings is that then they’re not consuming.

The good news here is they’re not using all their savings to pay down debt. It’s like a buffer, which is sitting there waiting to be deployed. This, I think is something to be optimistic about. It’s a good, good result. There is huge support for additional government fiscal support in this enormously polarised time politically. It doesn’t matter what political stripes you wear. Everyone is in favor of additional support, cynically, you might think “well, they would be”. But on the other hand, people prefer to actually go back to work than to get enhanced unemployment benefits, in the sense that, if they had to choose between going back to work and taking increases in unemployment benefits, they actually prefer to go back to work. This I think is good.

Katie Klingensmith: There’s concern around the economy, potential increase in defaults. Where do you see the yields really justifying the risks?

Sonal Desai: I think it depends on whether you’re looking at the yields or you’re looking at the spreads. And I think you will hear from many people that spreads are not quite yet at their all-time heights, but given where [US] Treasuries are, the absolute yields we’re getting in various sectors certainly makes them distinctly less attractive than they have been, historically. Having said that, it’s not as if one can simply determine, not to hold fixed income. I would say it’s a time to really look more at reducing duration in some cases because curves are so flat—what is the point of taking on massive quantities of duration at a time when you’re getting paid very little for that additional risk, which comes with that length and duration. I think holding a part of your portfolio in fixed income requires you to do a series of different things. One is to go global. You do need to look at other advanced economies. You need to spread and diversify your risk a little bit. I don’t think you can simply discard holding high yield. You just need to be active. It’s not a good time to buy the entire index precisely because I do think that within high yield, we’re going to see areas where we have an increase in defaults and so that you need the equivalent of stock-picking. I think you do need active managers who pick and choose the precise areas that they’re in. We have a lot of people who are pensioners. We have liability-driven investors. Yield is required. Income is required.

Katie Klingensmith: Let’s turn to equity markets now and bring in Scott Glasser from ClearBridge. Scott, a lot of large market swings of late, but overall, there still seems to be what many view as a significant disconnect between Main Street and Wall Street.

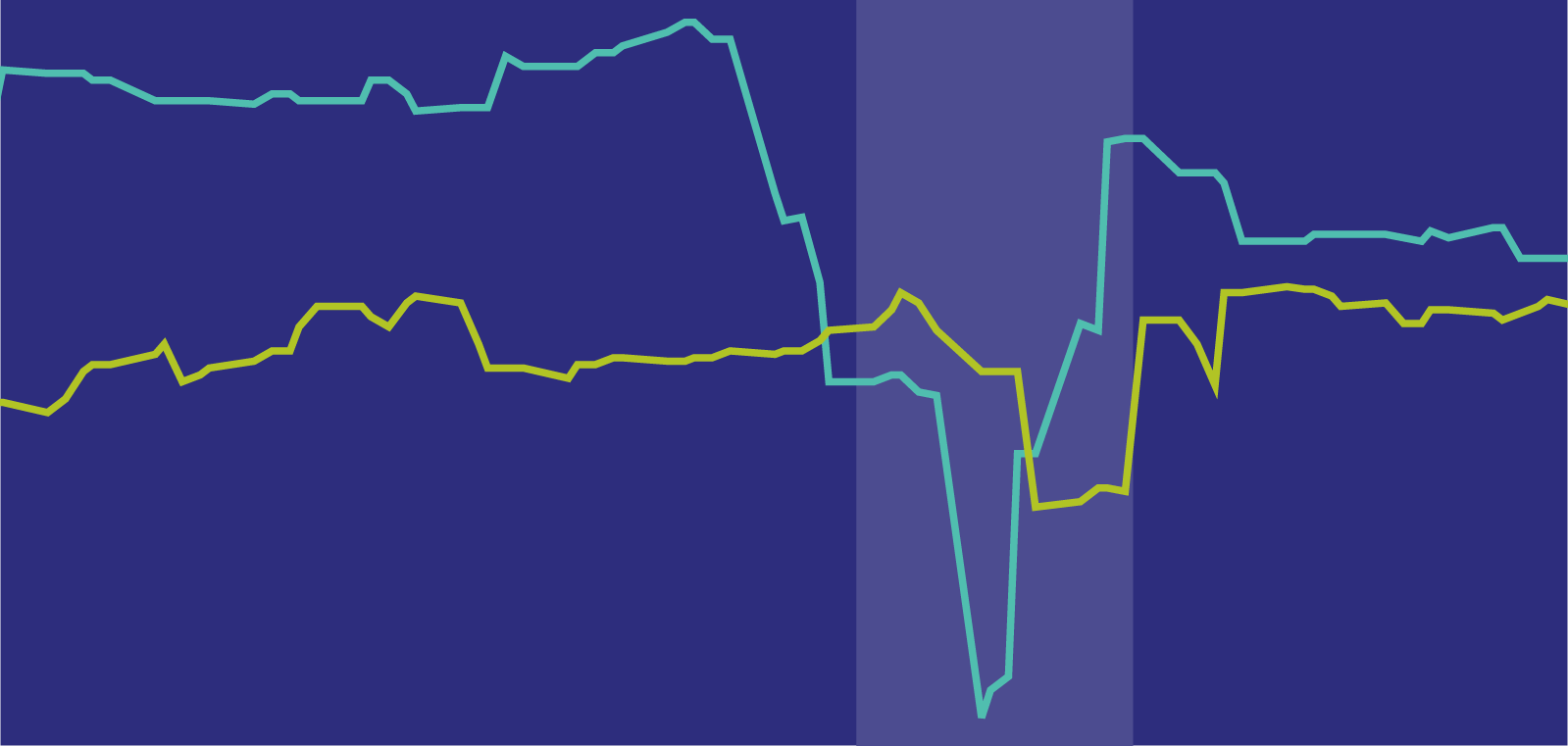

Scott Glasser: So I think that the disconnect that you refer to is common when you have basically sharp declines and big rebounds. So, so it’s not unusual but of course the market is discounting future improvement in the economy and so you certainly do have a disconnect. I mean, I think you need to look back a little. The pace of the decline on the way down was unprecedented. And really the rebound itself was unprecedented as well. Meaning how fast we rebounded from that decline. What is extraordinary is how fast the markets received both fiscal and monetary stimulus and really the amount of liquidity that was put in the system. So while there is a disconnect between the economy itself and what the market is saying, there isn’t a disconnect when you throw in the enormous amount of liquidity that was put in to bridge the weakness in the economy. Of course, there are questions at what point and how strong is the economy come back in the future? But right now there’s a battle between the economy and liquidity and liquidity wins, and that’s what supporting the market. The decline was an institutional selloff, primarily of quant-orientated funds that were overleveraged; you had US$500 billion of money come out of the market, which is what caused the rapid decline. About US$200 billion of that has been kind of put back into the market. And we’ve also had the reemergence on the retail side over the last several months. It’s led to some excesses in certain parts of the markets—tech in particular, but I think that that both the decline was justified and the rebound is justified and the disconnect exists, but that’s normal in terms of the recovery.

Katie Klingensmith: So, we have the battle between the real economy and liquidity, with liquidity winning. But how long can that last, and how do you view the future, a couple of years out?

Scott Glasser: My worry is that we put this money in the system and there will be a period of time, as we go into next year and beyond, where the incremental or the second derivative of that, will start to decrease. You won’t be increasing the liquidity in the system. As a matter of fact, it certainly will flatten out, potentially decrease over time. At some point Main Street needs to come back and fill the void that liquidity, you know, can no longer provide. So the extra juice, the extra adrenaline, the extra steroids, that kind of are pumped into the system, right, has kind of a waning effect over time. The real economy needs to kind of offset that over time. That’s my worry as you look out. We think that it’ll take two or three years for the US economy to get back to where it was pre-COVID. So, during that intervening period of time, what happens?

Katie Klingensmith: Scott, I’m going to come back to you in a minute to talk about tech and some other sectors to keep an eye on, but first, liquidity is also impacting commercial real estate, not to mention, a major shift in just how people work with so many now not in the office but at home during the pandemic. For perspective on that, we turn to Dave Gilbert from Clarion Partners. Dave, what did the fundamentals look like, pre-COVID, and now what are you seeing in during the pandemic?

Dave Gilbert: Going into COVID, we were near the end, as we now know it, of the longest expansions in the history of a real-estate cycle and with the healthiest fundamentals, meaning low vacancy rates, strong demand, and conditions were really remarkably good. You know, one of the first things impacted in COVID was where people work or this work-from-home phenomenon, something we frankly had never tested and had not anticipated. It’s been a fascinating test because, things I think for everyone have worked. Businesses have performed much better and been able to make that transition. The impact on the real estate market, frankly, is a little bit frightening only because we’ve now proven that many people can very effectively work from home and in fact, may even prefer work from home. Time will tell, which is a remarkable reverse from the single greatest, sort of cyclical, or maybe even secular trend that we had observed, which is reurbanisation and the desire for millennials—the need for them to work closely together in collaborative workspaces in dense urban environments. If you were an employer and you wanted to attract talent that’s where you needed to be, and that’s where we’ve seen remarkable growth in rents and that sort of thing in the hottest, primarily tech-oriented markets like San Francisco, Seattle, New York, etc.

Listen, we’re a firm believer that there’s still going to be a role for office and this notion of working from home forever—if you homeschool children and you spend three months in an effectively, a lockup, you’re quickly reminded of the benefits of getting out to an office. And, beyond that, you’ve got all of the other, massively important trends that existed pre-COVID and they were most notably, how do you attract talent, particularly in the tech world? And that was urbanisation, densification and collaboration. So, we took office space from an average of 250, say square foot per employee to about 125 square feet, almost down by 50%, because this next generation wanted to be together and needed to work very closely, collaboratively. I don’t think that ends.

What has been shocking in a way though, is many of those same tech firms that were on the cutting edge of every one of those trends have actually been at the leading edge of saying we can work from home. So, it’ll be interesting to see how it all balances out. The other phenomenon we’ve seen of late given the rising cost of living in many of these highly dense, super-popular areas like a San Francisco, for instance, some of the migration out to the secondary markets like in Austin or in Nashville. We think that will probably accelerate. So I think there’s going to be a continued need for office, although it may transition.

The other mega trend is e-commerce. And it has had tremendous impact on demand for industrial distribution properties and that has been fantastic and we don’t think that’ll reverse. Depending on market, e-commerce penetration rates are rising rapidly, clearly accelerated by COVID, but we think that just accelerates a trend that was underway anyway, and that’s at the detriment of brick-and- mortar retail. You see store closures and all the challenges there, but gross sales they’re still quite good. So the distribution changes, and there’s a role for the physical, for the brick-and-mortar. It’s changed a bit perhaps from malls now to warehouses.

Katie Klingensmith: Obviously, interest rates are important for real-estate investing. How much has the low-[interest] rate environment in general, but specifically the big drop in the policy rates affected the real estate landscape?

Dave Gilbert: Debt financing is important, less so in institutional portfolios, private investors, utilise it at a much greater degree, so it does have an impact, again, less on institutional and much more in private portfolios. And we’ve seen probably a 25-to-50 basis point decline in borrowing rates as a result of all the stimulus, which we’ve talked about, so pre-COVID to post-COVID, and that is helpful. It’s meaningful. The agencies in particular for, for apartments, multifamily investing continue to provide a lot of liquidity. In fact, their lending volumes are way up. The rest of the commercial real estate market lending volumes are down. And I think that’s a function less of available liquidity and more of less transactional activity, and most borrowers to the extent that they can, if there’s, if you’re facing a short-term decline in collections because of some of the suspension of rent payments, and that sort of thing has been going on, have worked with their lenders to forbear or defer. So, they’ve just put off the issue of refinancing, but there is ample liquidity in the debt markets, as it has been throughout this entire cycle and real estate has benefitted. Spreads for where we acquire assets to comparable, either Treasuries or even Baa bonds are a little higher than historically, which would suggest that there’s still some benefit in the future to real estate spreads.

Katie Klingensmith: Scott, let’s come back to you now and get your take on the biggest market- mover right now, and that’s tech, which had the incredible run and is now in the middle of a correction. What’s your take on it?

Scott Glasser: Tech has been the driving force since the bottom. I don’t think there’s much debate about that. There are very good reasons for that we all know. I mean, if you look at the beneficiaries of what’s gone on, in the whole online and move to digital, you took a trend that was in place, and really you accelerated that trend to an incredible degree and these companies are beneficiaries. Now they’re the obvious beneficiaries. They provide video services. There are the less obvious ones like tele-health, which you moved the whole industry forward. Education, you’re going to see a lot more, retail—I mean, the importance of omni-channel and the importance of having an online presence and using that as a tool, all of these things have been moved forward. Has it gotten over done? In certain segments and certain stocks, absolutely. I think you can look at things like the DART [Daily Average Revenue Trade] level. So, you look at Schwab and you look at E*TRADE and you look at their DARTs or revenues per trade, and you see an enormous pickup in trading in these types of stocks.

There are certain elements of the tech market that remind you of 2000. It’s not 2000, but it reminds you of 2000 kind of the momentum driven buying. Buying begets buying and unbelievable daily moves. Just to put that in perspective, it is not 2000. You know, 2000 we had a 6% bond yield, so things from a liquidity standpoint were tightening. The P/E [price/earnings ratio] on the tech sector was over 50–it’s now 25 for the sector as a whole. Certain stocks within it are much higher. You had the NASDAQ 100 Index—the NDX, 55% above its 200-day moving average. Now it’s 30% percent above it. And then you’ve seen an extreme move recently, you know, back against that and now you’re seeing a healthy correction from that one that I believe is still ongoing. And so that’s a healthy move. Has it gotten overdone? Yes, and we’re correcting those excesses. Do you want to own them for the next several years? Do you want to own the cloud? Do you want to own digitalisation plays? Do you want to be thinking about more home entertainment plays? Because a lot of this, as we already know, have moved into the home. So, I think that there are a lot of opportunities, but they are longer term in nature.

Katie Klingensmith: Speaking of longer term, what are some sectors really out of favour right now that you wouldn’t be so quick to cast off?

Scott Glasser: I do think getting out into that multi-year period that you’re going to have, you know, forgotten groups like utilities that will come back into play. The appeal of a 3.5% to 4% dividend yield in a zero interest-rate environment, I think makes sense. They’re completely out of favour now. Nobody cares about them.

Health care is another sector that I think gives you the attributes of kind of being aggressive offensively but playing defense. Nobody likes them, at least on the pharmaceutical side—medtech has done much better, but pharmaceuticals right now are at a 30-year relative low in terms of their valuations. So I do think there are areas of the market that are attractive. I don’t think everything is inflated but there are certain areas that are inflated. And so I do advocate a more diversified, kind of barbelled approach.

Katie Klingensmith: I want to end on our discussion on the topic of inflation. The Fed has changed its position, saying it will now target inflation that averages 2% over time, meaning it could run over the 2% following a period of low inflation. Sonal, do you see inflation as a concern, especially with the fiscal policy measures in place?

Sonal Desai: Historically, I have not been a massive fan for the extent of time that we continue to see QE [quantitative easing] post the global financial crisis, but actually the speed with which the Fed stepped up this time around, they have to get credit for that.

But the other side of that of course is how long it will last. And the fact that we have this enormous amount of easy fiscal policy. In case we all forget, by the end of this year we will probably have a budget deficit, which was seen last in 1943 during World War II, in terms of being close to 25% of GDP. We’re doing this at the same time that the QE we’re looking at is probably larger than QE one, two and three put together done in a much shorter period of time. I know that maybe it’s unfashionable to worry at all about inflation, but looking much further out, I think that we do have to worry about it a bit. The US is not going through deflation. So, this kind of policy easing does come with some concerns further down the road, because the Fed is going to tell us that rates are going to be low for the longest time ever. They’ve essentially already told us this.

Katie Klingensmith: Well, I would like to thank everyone so much for joining me today. Dr. Sonal Desai, Chief Investment Officer of Franklin Templeton Fixed Income. Scott Glasser, the CIO of ClearBridge Investments, and Dave Gilbert, CEO and Chief Investment Officer of Clarion Partners.

Host:And thank you for listening to this episode of Talking Markets with Franklin Templeton. If you’d like to hear more, visit our archive of previous episodes and subscribe on iTunes, Google Play, Spotify, or just about any other major podcast provider. And we hope you’ll join us next time, when we uncover more insights from our on the ground investment professionals.

*****

Important Legal Information

This material reflects the analysis and opinions of the speakers as of September 15, 2020 and may differ from the opinions of portfolio managers, investment teams or platforms at Franklin Templeton. It is intended to be of general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice.

The companies and case studies shown herein are used solely for illustrative purposes; any investment may or may not be currently held by any portfolio advised by Franklin Templeton. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

The views expressed are those of the speakers and the comments, opinions and analyses are rendered as of the date of this podcast and may change without notice. The information provided in this material is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region, market, industry, security or strategy. Statements of fact are from sources considered reliable, but no representation or warranty is made as to their completeness or accuracy.

What Are the Risks?

All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal. The value of investments can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Stock prices fluctuate, sometimes rapidly and dramatically, due to factors affecting individual companies, particular industries or sectors, or general market conditions. Bond prices generally move in the opposite direction of interest rates. Thus, as prices of bonds in an investment portfolio adjust to a rise in interest rates, the value of the portfolio may decline. High yields reflect the higher credit risk associated with these lower-rated securities and, in some cases, the lower market prices for these instruments. Interest-rate movements may affect the share price and yield. Treasuries, if held to maturity, offer a fixed rate of return and fixed principal value; their interest payments and principal are guaranteed. Real-estate securities involve special risks, such as declines in the value of real estate and increased susceptibility to adverse economic or regulatory developments affecting the sector. Investments in REITs involve additional risks; since REITs typically are invested in a limited number of projects or in a particular market segment, they are more susceptible to adverse developments affecting a single project or market segment than more broadly diversified investments. The technology industry can be significantly affected by obsolescence of existing technology, short product cycles, falling prices and profits, competition from new market entrants as well as general economic conditions. Investments in fast-growing industries, including the technology and health care sectors (which have historically been volatile) could result in increased price fluctuation, especially over the short term, due to the rapid pace of product change and development and changes in government regulation of companies emphasising scientific or technological advancement or regulatory approval for new drugs and medical instruments. Actively managed strategies could experience losses if the investment manager’s judgment about markets, interest rates or the attractiveness, relative values, liquidity or potential appreciation of particular investments made for a portfolio, proves to be incorrect. There can be no guarantee that an investment manager’s investment techniques or decisions will produce the desired results.

Diversification does not guarantee profit or protect against risk of loss.

There is no assurance that any estimate, forecast or projection will be realised.

Data from third party sources may have been used in the preparation of this material and Franklin Templeton (“FT”) has not independently verified, validated or audited such data. FT accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss arising from use of this information and reliance upon the comments opinions and analyses in the material is at the sole discretion of the user.

Products, services and information may not be available in all jurisdictions and are offered outside the U.S. by other FT affiliates and/or their distributors as local laws and regulation permits. Please consult your own financial professional for further information on availability of products and services in your jurisdiction.

Issued in the U.S. by Franklin Templeton Distributors, Inc., the principal distributor of Franklin Templeton’s U.S. registered products, which are available only in jurisdictions where an offer or solicitation of such products is permitted under applicable laws and regulation. Issued by Franklin Templeton outside of the US.

Please visit www.franklinresources.com to be directed to your local Franklin Templeton website.

ClearBridge Investments and Clarion Partners are wholly owned subsidiaries of Franklin Resources, Inc.

Copyright © 2020 Franklin Templeton. All rights reserved.