by Cameron McVie, Russell Investments

Virgin Galactic, which plans to offer space tourism. DraftKings, which offers online betting. Nikola, which is developing electric trucks. Immunovant, which develops treatments for autoimmune diseases. What’s the common thread of these four companies in very different industries? They were all taken public through a special purpose acquisition company (SPACs) over the past year.

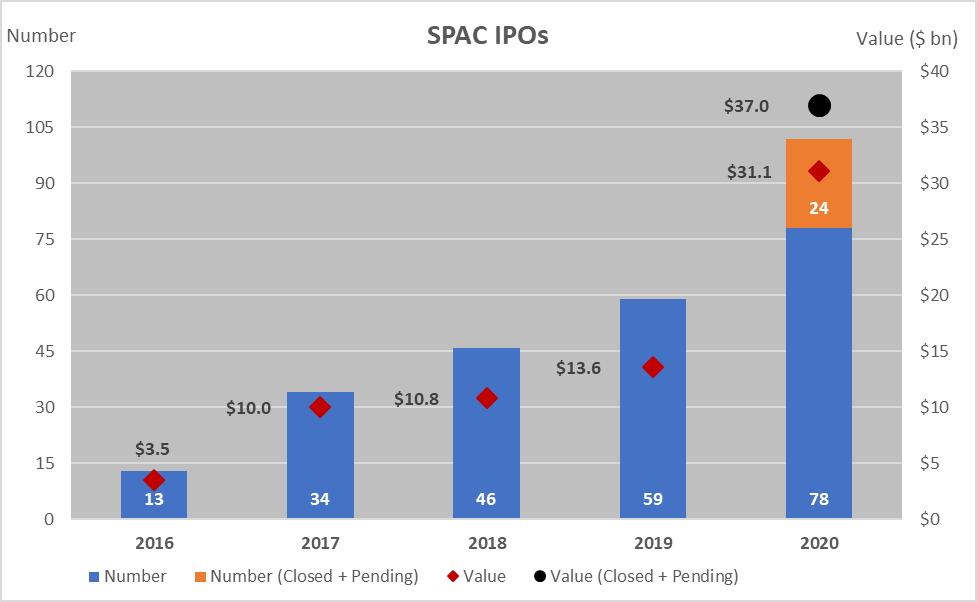

Click image to enlarge

Source: SPAC Research, as of Aug. 24, ,2020

There’s no doubt about it: SPACS are hot. So far in 2020, almost 80 SPACs have raised capital through initial public offerings (IPOs), with an average transaction size of $400 million. In addition, a further 24 SPACs worth an addition $6 billion have filed and are pending. Total SPAC capital raised in 2020 is approaching the sum total of capital raised in the 2017-2019 period.1 But these figures don’t address the fundamental question on many investors’ minds: are SPACs good investments? Our definitive answer is maybe.

Anatomy of a SPAC

A SPAC is formed by a sponsor, which consists of a management team that will invest initial capital alongside outside investors. The sponsor’s responsibility is to identity a private business or asset to be purchased at an attractive valuation, with the end objective of making this target a publicly-listed company by combining with the SPAC. The sponsor will generally have expertise in specific industries from where the target is selected, and will manage the selection, acquisition process, regulatory and legal reviews, and financing needs.

A SPAC differs from a traditional IPO in that the latter takes an identified, privately owned business through an IPO process. This requires an extensive registration process with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), including providing detailed financial disclosures, business history, risks, etc. In contrast, a SPAC does not yet have an identified business to purchase, and therefore, it raises capital with more limited disclosure.

Interests in a SPAC are offered as units at a price of $10, which consist of a share plus a fraction of an out-of-the-money warrant. For example, a typical structure would be for the exercise price to be $11.50 with a mandatory conversion price materially higher than that. The sponsor will invest in the SPAC and cover expenses in exchange for receiving 20% of the units at a discount to the offering price.

Proceeds from the SPAC’s capital raise are held in a trust account that can only be released for one of three reasons: (1) to fund the business acquisition; (2) to fund shareholder redemptions; or (3) to pay shareholders in the event of the SPAC’s liquidation if it can’t complete a transaction within a specified time frame (usually two years).

In addition to owning shares and warrants in a SPAC, an investor also has an embedded put option. When an acquisition is announced, the investor has the right to retain their holdings or to redeem their units at the initial investment cost plus any accrued interest. This provides the investor with several ways to manage the position prior to a deal announcement. They may:

- Retain the entire unit (shares and warrants)

- Sell the entire unit if trading at a premium to net asset value (NAV)

- Sell the shares but retain the warrants to gain from any future upside from a completed deal

With SPAC proceeds held in trust, the sponsor can take no compensation until a transaction is completed. If a target is not identified and a deal fails to materialize within the stipulated timeframe, the sponsor loses their capital investment, with residual proceeds returned to outside investors. In this way, they are incentivized to ensure a deal is completed and are aligned with outside investors.

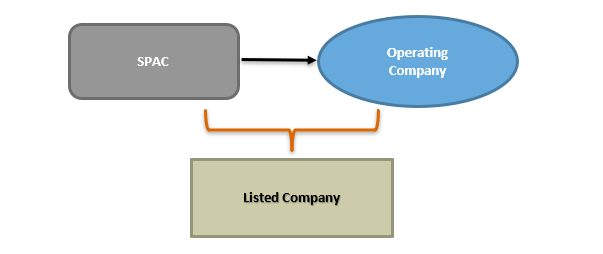

The de-SPAC

If the sponsor is successful in identifying and acquiring a target entity, it will be merged with the SPAC into a single, publicly listed business combination in what is known as a de-SPAC transaction. The new company will then be subject to the normal requirements of a public company. Because any investor may choose not to participate in the SPAC transaction, the sponsor does not know with certainty what percentage of the trust assets will be available to consummate the transaction. Because of this, it’s common for sponsors to enter into forward purchase agreements with some of the early investors that can be called on to provide extra financing for a transaction. Additionally, the sponsor can raise extra cash through a private investment in a public equity (PIPE) transaction.

Click image to enlarge

Making money in SPACs

As the SPAC market has proliferated, we are not surprised that there have been announcements of exchange-traded funds (ETF)s that will invest in the SPAC market. This could be quite a risky proposition, since in general, we believe that active managers are key to generating positive excess returns in speculative companies.

Although some de-SPAC deals have been quite successful, the post-merger performance of companies has been mixed, with a wide dispersion of outcomes. On average, SPAC transactions underperform broader equity markets in the subsequent years.

In a recent report, Goldman Sachs2 noted that in 56 completed transactions since January 2018, on average SPAC equities initially outperformed the broader equity market, but then significantly underperformed over the subsequent three-, six-, and twelve-month period. In addition, the range of outcomes was extremely wide, with the top decile generating >60% returns, while the bottom decile lost more than 80% of their value.

This may be explained due to the fact that companies acquired by SPACs are often highly speculative, with unproven business models and little or no cash flow. Electric vehicles (EVs) have been a fertile area for SPACs in 2020: Nikola, Lordstown Motors, Fisker and Canoo have either finalized or pending SPACs. While each of these companies may appear to be a compelling investment in isolation, we note that there are other companies competing in the EV market, including Tesla, Rivian and the legacy global auto manufacturers.

While we believe that profitably investing in SPACs is possible, we view active selection as essential. Experienced investors may use their industry expertise to back the most skilled sponsors, who are likely to have the highest probability of success. In addition, the terms of various SPACs may have various nuances that ensure better outcomes for investors, as opposed to a free blank check for the sponsors, which is often cited in the media. Furthermore, the warrants that are inherent in the SPAC units provide their own opportunity for sophisticated investors to trade what are often highly volatile share prices.

So again, are SPACs a good investment? Maybe.

1 Source: Goldman Sachs, US Weekly Kickstart, July 31, 2020

2 Source: SPAC Research, as of Aug. 24, 2020

Copyright © Russell Investments