by John Feyerer, Senior Director of Equity, ETF Product Strategy, Invesco Canada

In 2020, U.S. equity markets have taken a path that few could have seen coming. As a result, the S&P 500 Index has become more top-heavy than it’s been in 45 years. Below, I explain why this is the case, what it means for investors — and what they can do to help mitigate this concentration risk while maintaining exposure to the companies that make up this well-known benchmark.

The S&P 500 Index is dominated by just five holdings

Since its low on March 23, the S&P 500 Index has recovered by nearly 50% on the back of historic government and central bank intervention.1 Not only has the index turned positive for the year, it is now rapidly closing in on its Feb. 19 high. During this year’s equity roller coaster ride, the five largest holdings in the S&P 500 Index – Microsoft (MSFT), Apple (AAPL), Amazon (AMZN), Alphabet (GOOG/GOOGL) and Facebook (FB) have shined brightly.2 The average year-to-date return among these largest five holdings is more than 36%,1 driven by the perceived safety of owning the biggest companies as well the importance of technology and communication services in the work-at-home/stay-at-home world suddenly thrust upon us by the Great Lockdown.

Why is this outperformance by the mega caps important? Like many benchmark indexes, the S&P 500 uses market capitalization to weight securities. This means that despite the significant number of securities that are included, the risk and return of the index — and of the traditional index funds that track it — is driven by the largest holdings. The dominance of just a few large holdings on overall risk and return is called “concentration risk.”

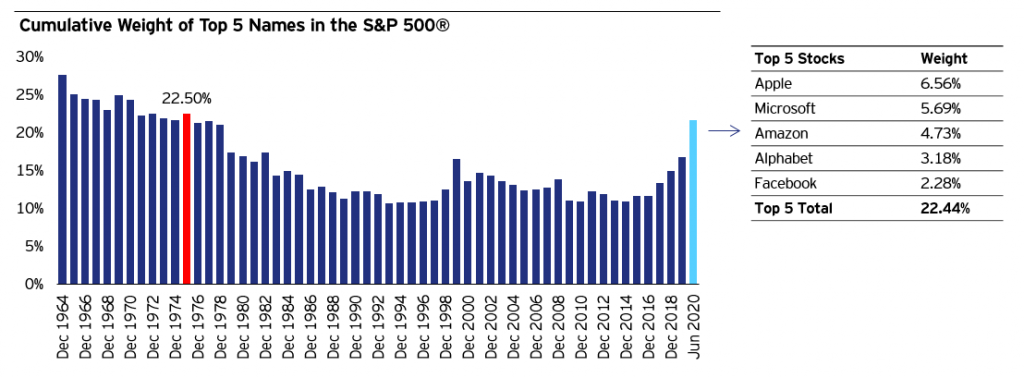

The recent run up in these “biggest of the big” companies has created a situation in which the S&P 500 Index is more top-heavy than it has been in 45 years. As of Aug. 7, the top five stocks accounted for nearly 23% of the weight in the S&P 500 Index, up from 16.8% at the end of 2019 and widely surpassing the 16.6% observed in December 1999 (which was in the midst of the final build-up before the technology bubble burst in March 2000).3

Benchmark indexes face historic levels of concentration risk

As shown in the chart below, the current concentration risk of the S&P 500 is only a few percentage points from the high of 27.7% reached in 1964.3 This amount of concentration risk is one that traditional passive investors haven’t faced in over four decades. When concentration risk is the simple result of market capitalization (versus, for example, the intentional choices of an active manager), it may leave investors vulnerable in a few different scenarios: When valuations mean revert, when new competitors have a negative impact on the top companies, when regulatory risk emerges, and when the market experiences a rotation into more cyclical stocks.

Concentration risk: The concentration in the top 5 holdings is nearly 23%, a level not seen since 1975

The light blue bar represents the current concentration figures as of Aug. 7. The red bar illustrates the last time that the concentration of the index’s top 5 holdings was this high.

Source: S&P Global and Bloomberg, L.P., as of Aug. 7, 2020. In 1975, the top 5 holdings were IBM, Proctor & Gamble, Exxon Mobil, 3M, and General Electric. An investment cannot be made directly into an index. Holdings are subject to change and are not buy/sell recommendations

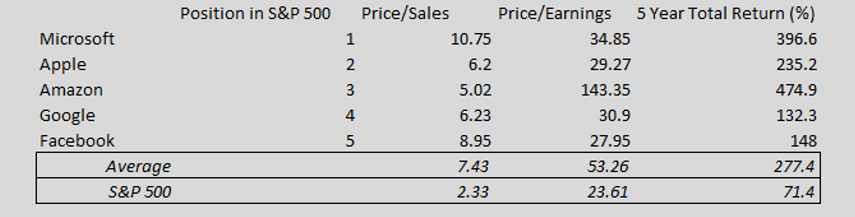

While the S&P 500 has enjoyed a healthy total return of 71.4% (11.4% annualized) since late July 2015, these five names had an average total return of 277% (30.4% annualized), nearly four times that of the S&P 500 Index from July 28, 2015-July 27, 2020.4 Their valuations have also expanded to the point that the average price/sales and price/earnings ratios for the top 5 are now 3x (7.43 vs. 2.33) and 2.3x (53.26 vs. 23.61) versus that of the S&P 500 benchmark, respectively.

Source: Bloomberg, L.P., as of July 27, 2020. An investment cannot be made into an index. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Against an ongoing backdrop of strength for these market giants, as evidenced by second-quarter earnings announcements, it is important for investors to remember that there are countless examples from financial history that tell us that the largest companies as measured by market capitalization do not maintain that lofty perch years into the future. As of today, the five largest companies in the S&P 500 have an aggregate weight that is higher than at any point since 1975, when the likes of IBM, Proctor & Gamble, Exxon Mobil, 3M, and General Electric were the biggest of the big.5

Consider an equal-weight approach

Investors looking to diversify away from these top-heavy benchmarks while still maintaining exposure to their holdings may consider an equal-weight approach. Equal-weight strategies weight each of their holdings equally, so that overall performance cannot be dominated by a very small group of companies. So, using the example of the S&P 500, each of the 500 index companies would represent approximately 0.2% of the portfolio in an equal-weight strategy.

The Invesco S&P 500 Equal Weight Index ETF – CAD (EQL) may provide a potential solution for those investors that may want to diversify their portfolio to help mitigate this concentration risk while still maintaining exposure to the S&P 500.

This post was first published at the official blog of Invesco Canada.