by Scott Brown, Ph. D., Chief Economist, Raymond James

Chief Economist Scott Brown discusses current economic conditions.

In her recent book, “The Deficit Myth,” Stephanie Kelton, a professor at Stony Brook University, writes about many of the common misperceptions surrounding government debt and deficits. Kelton is a proponent of Modern Monetary Theory, an approach widely rejected by academic economists, and was an advisor to Bernie Sander’s 2016 and 2020 presidential campaigns. However, her rebuff of popular deficit myths does not run counter to the mainstream view of most economists.

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is a non-standard theory, meaning that it is not widely accepted by economists, especially in academia. That doesn’t make it wrong, but mainstream macroeconomics is built on a more solid foundation (that doesn’t make it perfect). The mainstream view is that monetary policy should be used to guide unemployment and inflation over the long term, with fiscal policy (government taxation and spending) the main tool in digging out of recessions. Neither is a tool to fine-tune the economy. In MMT, fiscal policy is used to control inflation. Interest rates are still important, but higher rates are seen as expansionary and lower rates are contractionary – exactly opposite to how monetary policy is conducted around the world. Kelton likens herself to Copernicus, changing the way economists and the general public look at the world. Well, isn’t that special?

The first myth Kelton tackles is whether we should think of the government budget the same way that we view household budgets. “Living within our means,” is a common political platitude, but the government is nothing likely a household. The government does not have to pay off its debt

– indeed, we wouldn’t want it to. Our kids and grandkids can easily pass the debt along to their kids and grandkids. We never paid off the debt from WWII. The key issue is whether we can make interest payments and roll over existing debt.

Another myth is that deficits are a sign of overspending. It seems self-evident that one could just as easily argue that deficits are caused by insufficient taxation, but Kelton takes it further in arguing that spending and taxation decisions are completely independent. That should also be self-evident, although one wouldn’t know that from hearing politicians speak. Republicans are serious about the deficit when a Democrat is in the White House, not so much when the president is a Republican. Democrats have long held to the view of paying for additional spending (either through tax increases or through spending cuts in other areas) – exhibit A is the Affordable Care Act, which was funded. In tough economic times, as we are seeing now, both parties have supported fiscal expansion, but more so in an election year. Kelton argues that, in normal times, the focus on the deficit has prevented us from making important investments. Without the self-imposed budget constraint, the U.S. could spend more on infrastructure, education, and public health.

Some argue that higher government borrowing crowds out private investment, as evidenced by the lackluster pace of capital spending over the last decade. However, that has been a worldwide phenomenon, not unique to the U.S. Moreover, corporate borrowing costs have been low over the last decade and cash balances have generally been high. In the 1980s, the national debt roughly tripled as a percentage of GDP. Yet, business fixed investment wasn’t any slower than it was in the 1970s.

Proponents of MMT admit that there are limits to government borrowing, but believe that there are no constraints in the near term. The government currently has no problem borrowing, interest rates are low, and the Federal Reserve is purchasing much of the additional borrowing. Mainstream economists, including Fed Chair Powell, still believe that fiscal balance is important in the long term, just not now. In his monetary policy testimony to Congress, Powell noted that the federal budget was on an unsustainable path prior to the pandemic. The 12-month deficit had hit $1 trillion and was rising. The deficit rose to 10% of GDP during the worst part of the financial crisis. We exceeded that in May, on our way to about 18% of GDP or more. That’s nothing to lose sleep over. We have plenty of time. The real danger is not doing enough to support the economy now and taking support away too soon.

What about inflation? In the Fed officials’ recent economic projections, inflation was expected to remain well below the central bank’s 2% target this year and next. With soft demand, here and abroad, there is unlikely to be much upward pressure in prices of raw materials or finished goods. The labor market is the widest channel for inflation pressure, and high unemployment should limit wage increases.

Much of what Kelton proposes is not out of the mainstream. While many economists have worried about government deficits and debt in the past, the general view now is more open. For example, Olivier Blanchard, who taught a generation of macroeconomists, shifted his view over the last decade, famously in an address to the America Economic Association in 2019. In the meantime, the government should do whatever it takes.

Economic Data for May

The mid-month economic data reports remained consistent with a strong bounce in activity as state economies re-open. Social distancing caused a sharp contraction in consumer activity in March and April, so the initial recovery will be sharp, but partial. Manufacturing output, which off the April lows, will likely take some time to recovery, reflecting softer domestic demand, but also a weak global economy.

Retail sales rose a record 17.7% in May, led by a 44.1% rebound in motor vehicles, with the biggest gains in areas that had taken the biggest hits during lockdowns (clothing stores, department stores, restaurants). However, May improvement followed sharp declines over the two previous months. Excluding autos, retail sales rose 12.4%, after falling 18.5% from February to April.

Industrial production rose 1.4% in May, held down by a 2.3% decline in the output of utilities and a 36.9% drop in oil and gas well drilling. Manufacturing output rose 3.8% (-16.5% y/y), with motor vehicles and parts up 120.8% (-62.8% y/y). Ex-motor vehicles, factory output rose 2.0% (-12.8% y/y).

Residential construction improved in May, following sharp declines in March and April. Single-family building permits rose 11.9% (-9.9% y/y). Single-family housing starts, which are erratic and unreliable, were essentially unchanged (+0.1%), down 17.8% y/y.

Gauging the Recovery

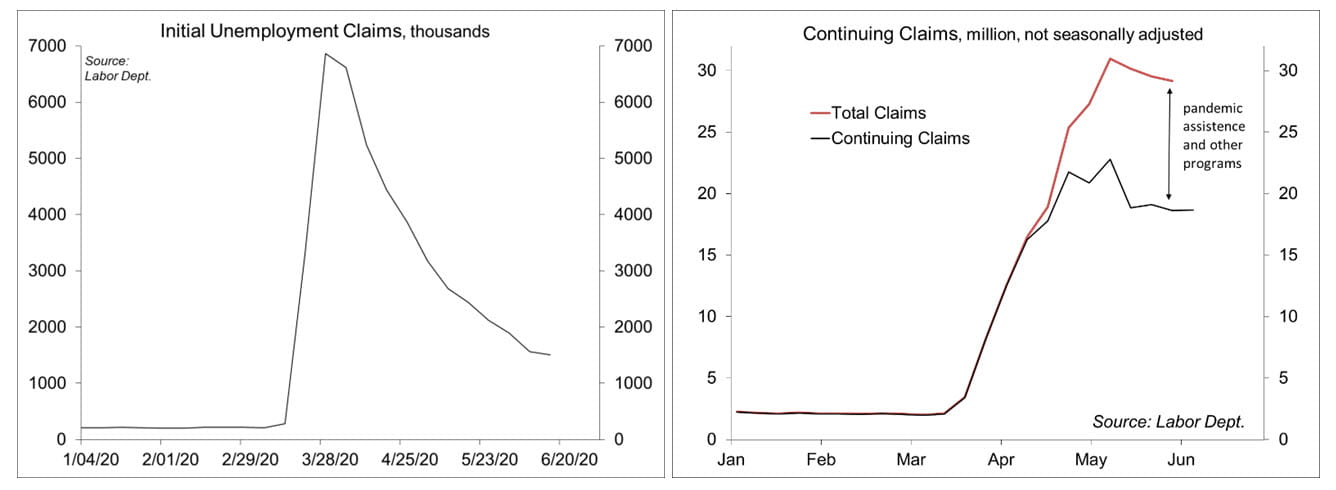

Jobless Claims fell to 1.508 million in the week ending June 13, trending down, but still very high. Continuing Claims fell by 62,000 in the week ending June 6, to 20.544 million (seasonally adjusted). The figures are for regular state unemployment insurance programs and do not include pandemic assistance and other programs. Total recipients, including all programs, were 29.166 million (not seasonally adjusted) for the week ending May 30 (down from 29.516 million in the week ending May 23). Pandemic assistance includes self-employed and part-time workers (who normally wouldn’t qualify for benefits), as well as individuals who had previously exhausted the unemployment benefits.

The New York Fed’s Weekly Economic Index rose to -8.39% for the week of June 13, down from -9.23% in the previous week and a low of -11.48% at the end of April. The WEI is scaled to four-quarter GDP growth (for example, if the WEI reads -2% and the current level of the WEI persists for an entire quarter, we would expect, on average, GDP that quarter to be 2% lower than a year previously).

The University of Michigan’s Consumer Sentiment Index rose to 78.9 in the mid-month assessment for June (the survey covered May 27 to June 10), up from 72.3 in May and 71.8 in April. Expectations remained weak. The report noted that “The resulting record level of income uncertainty has had a significant impact on consumers' willingness to make discretionary purchases, although uncertainty has slightly eased recently.”

The opinions offered by Dr. Brown should be considered a part of your overall decision-making process. For more information about this report – to discuss how this outlook may affect your personal situation and/or to learn how this insight may be incorporated into your investment strategy – please contact your financial advisor or use the convenient Office Locator to find our office(s) nearest you today.

All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the Research Department of Raymond James & Associates (RJA) at this date and are subject to change. Information has been obtained from sources considered reliable, but we do not guarantee that the foregoing report is accurate or complete. Other departments of RJA may have information which is not available to the Research Department about companies mentioned in this report. RJA or its affiliates may execute transactions in the securities mentioned in this report which may not be consistent with the report's conclusions. RJA may perform investment banking or other services for, or solicit investment banking business from, any company mentioned in this report. For institutional clients of the European Economic Area (EEA): This document (and any attachments or exhibits hereto) is intended only for EEA Institutional Clients or others to whom it may lawfully be submitted. There is no assurance that any of the trends mentioned will continue in the future. Past performance is not indicative of future results.