by Craig Basinger, Derek Benedet, Chris Kerlow, Alexander Tjiang, Richardson GMP

The economy has always moved in cycles from expansion to peak to recession to trough. Rinse and repeat. Of course the timing, duration, magnitude and composition of these cycles is different each time, but there are also many similarities. For instance, most recessions have an epicenter that for whatever reason grows too big and then collapses. Sometimes there is an external shock, but this usually sets in motion the collapse that would have likely occurred later. The collapse at the epicenter then causes a domino effect involving other industries, employment, spending and presto, we have a recession. Often, central banks raise rates ahead of the recession and take the blame. However, the policy is often designed to slow the growth, namely the growth within the epicenter, but monetary policy is a blunt tool. The cycle occurs and ends due to enhanced returns triggering “animal spirits” that go too far.

The recession we are in today is very different, which makes it less comparable. For starters, this recession is self induced, to combat a public health crisis. And its epicenter appears to be the service industry, which is also very unique. We have never (to our knowledge) gone through a services-driven recession.

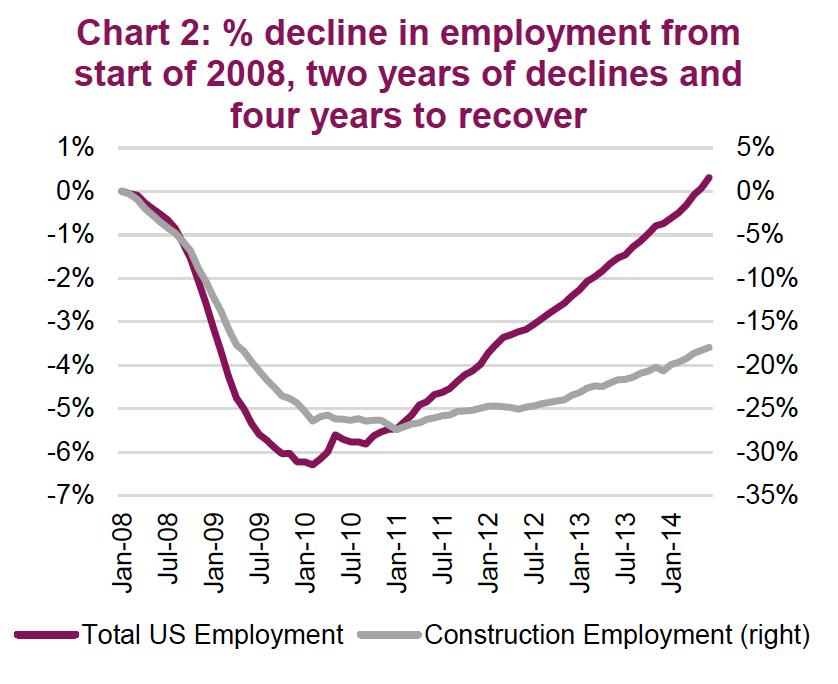

In the run up to the 2008/2009 recession, there is no doubt the U.S. was building too many homes. Low yields helped keep prices rising which encouraged more and more people to jump in as new homeowners or speculators on multiple homes. Lax regulations and financial engineering also contributed, but at the core it was investors trying to make money that drove things too far. As this growth started to collapse, it sent vibrations across the entire economy which culminated in the great financial crisis (GFC) and recession. We never thought we would call the GFC typical, but in today’s world it is.

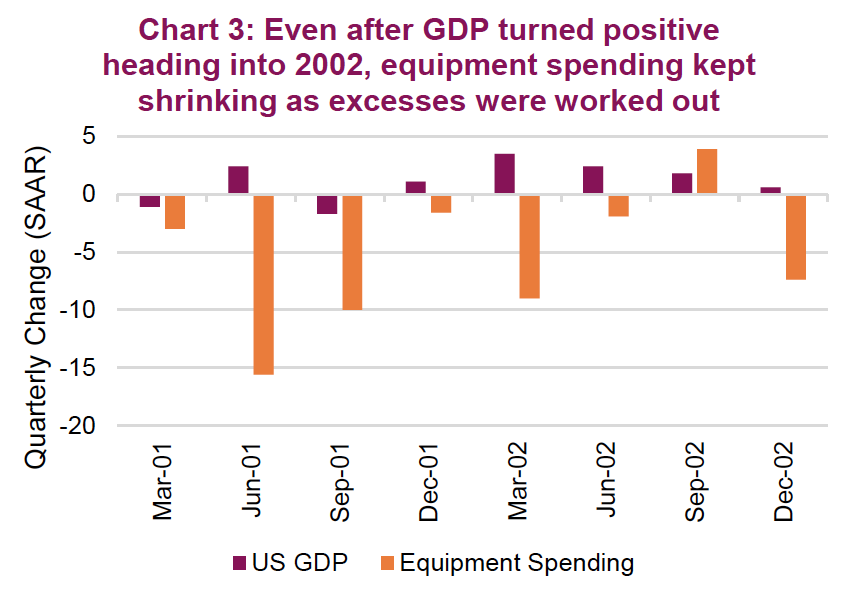

In the late 1990s, there was the tech boom. The awesomeness of the internet was going to change the world, and it did; but once again those animal spirits went too far, too fast. Amazing gains in the stock market attracted more capital that funded some rather questionable business plans. As the bubble burst, it dragged down even those with more substantive businesses. Corporate spending was dramatically reduced, capital costs were higher, and this started the domino effect that pushed the economy into a shallow recession.

In the early 1990s, the recession was triggered by too much debt accumulation, the Savings & Loan (S&L) crisis and some real estate weakness.

What makes 2020 so different?

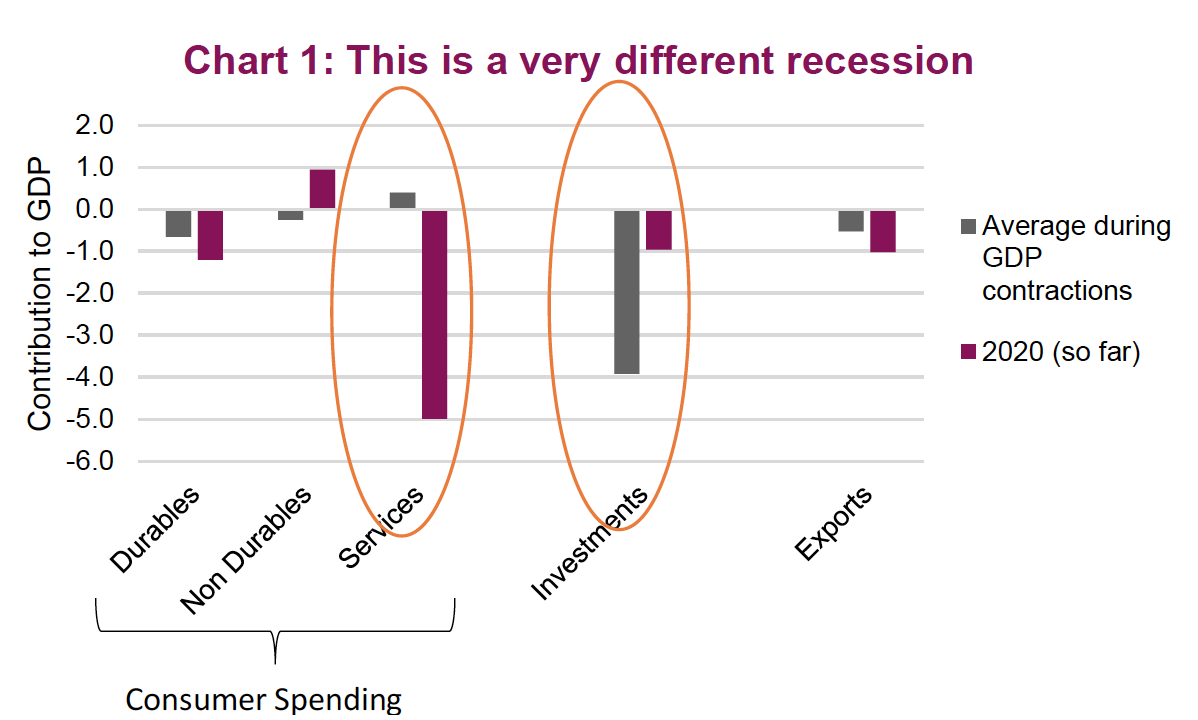

The 2020 recession has some similarities with past recessions, but some material differences make comparisons with the past difficult. At this point, it remains unclear if there were any pockets of material excess that had built up – maybe corporate debt but that remains very uncertain. With no excesses, this may be some very good news.

For instance, in the 2008 recession, employment declined for two years before bottoming, and took four years to recover (Chart 2). Construction jobs, clearly at the epicenter of the housing bust, took a decade to get back to previous levels. After all, the U.S. had been constructing houses for years at a pace that well exceeded the natural demand from household formation and net immigration. This excess inventory took years to work through. The recession of 2001/2002, which had excess spending in technology, saw investment in equipment (that is where tech spending sits in economic terms) continue to be a drag on the economy for years after the recovery started (Chart 3). Again, it took years to burn through the excess.

A recession with the services industry at the epicenter really doesn’t have any excesses to work through. As demand disappeared due to social distancing, many services and service jobs also disappeared. But they will reappear (perhaps under different signage) and re-hiring will commence as demand returns. The recovery in these industries won’t be as fast as the declines, but as demand returns it won’t take four years to re-hire.

Trying to guess the path and speed of the relaxation of social distancing rules is somewhat pointless as it will change and evolve over time. However, we may garner some insights from micro markets. One of the hardest hit service industries over the past few months has been restaurants. Those that had takeout options had a small lifeline, but most shut down completely with zero seated patrons for multiple months. The road to recovery won’t be as fast as the drop, but it will be faster than past recessions as we approach the “new normal”.

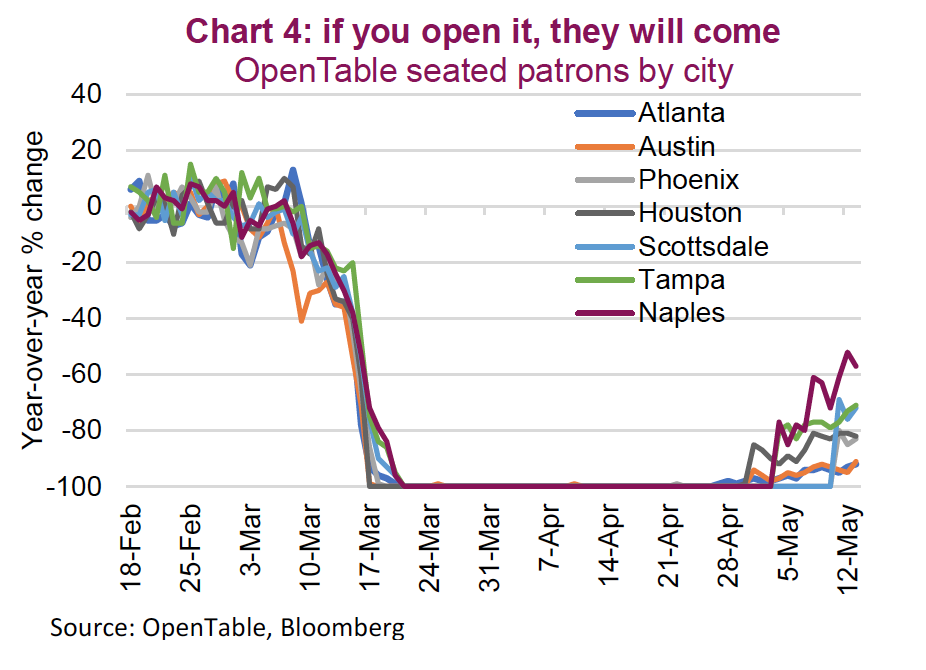

The popular reservation app OpenTable tracks year-over-year changes in seated patrons (Chart 4). In the U.S. in March, the number of seats dropped 100%, but as some states have started to relax distancing and open up, we can see in real time the response by consumers. We’re seeing the green shoots of normalcy and pent-up demand for dinner with friends and family play out in southern states. The city of Naples, Florida is leading the charge, as are other cities in Arizona and Texas. These states opened restaurants in early May so we can see the gradual rise. The big question is at what point do they stabilize. This will be the “new normal”.

While there is no question this will stabilize somewhere below year-ago levels, the path does provide a look at the potential path to recovery. Capacity constraints, virus fears and a consumer that will likely prefer to save more on the margin, will all contribute to a more muted new normal. Not to mention that, according to an OpenTable survey, 25% of restaurants may likely not reopen. The hospitality industry is probably one of the oldest in the world, and has survived through countless wars, famines and diseases that were far more deadly. Will consumers change after corona? Absolutely, but eventually we’ll adapt. It’s what humans do best: we adapt to our changing circumstances and survive. Consumers and business will adapt to minimize the collateral damage and the pace of recovery could be surprising.

The incomparable recession

The pandemic’s sudden impact on the global economy and social distancing have created a recession unlike any other. Adding to the uniqueness is the fact that massive policy responses were instigated almost simultaneously around the world. And so to has the fact that the pain so far has centered mainly in services, an area of the economy that has historically been a stabilizer during periods of negative GDP growth.

While weakness in services could spread and drag down other areas of the economy, we believe a sharper, albeit partial, rebound in services will make this less likely. Don’t get us wrong, this is going to be a very painful recession that is deeper than most. And after the bounce off the bottom, behaviours will have changed. Savings will likely be higher than normal as individuals repair their balance sheets and create that rainy day account. Social distancing will limit the recovery in some areas of the economy.

The good news is that compared to past recessions, which had to work through excess inventories of houses or tech, this one doesn’t have such a burden. Instead of suffering two years of job losses and a long four years to get back to normal, this recession may have a similar pattern but over quarters. Of course, there are many unknowns as we are in the uncharted waters of a novel services recession.

Source: All charts are sourced to Bloomberg L.P. and Richardson GMP unless otherwise stated.

The opinions expressed in this report are the opinions of the author and readers should not assume they reflect the opinions or recommendations of Richardson GMP Limited or its affiliates. Assumptions, opinions and estimates constitute the author's judgment as of the date of this material and are subject to change without notice. We do not warrant the completeness or accuracy of this material, and it should not be relied upon as such. Before acting on any recommendation, you should consider whether it is suitable for your particular circumstances and, if necessary, seek professional advice. Past performance is not indicative of future results. The comments contained herein are general in nature and are not intended to be, nor should be construed to be, legal or tax advice to any particular individual. Accordingly, individuals should consult their own legal or tax advisors for advice with respect to the tax consequences to them, having regard to their own particular circumstances. Insurance services are offered through Richardson GMP Insurance Services Limited in BC, AB, SK, MB, NWT, ON, QC, NB, NS, NL and PEI. Additional administrative support and policy management are provided by PPI Partners. Insurance products are not covered by the Canadian Investor Protection Fund.

Richardson GMP Limited, Member Canadian Investor Protection Fund. Richardson and GMP are registered trademarks of their respective owners used under license by Richardson GMP Limited.