by Brian Levitt and Talley Leger, Invesco Canada

To retest or not to retest – that is the question. Indeed, if Hamlet were around today he may be wondering whether the broad U.S. equity market, after posting the second best 25-day rally on record (trailing only 2009’s), will retest the initial market low hit on March 23 of this year.1 To many investment professionals, a retest of the market bottom is a foregone conclusion. In fact, a poll of financial advisors conducted in early April revealed that 81% expected the U.S. equity market to retest the March 23 low.2

The results of the poll are not a surprise. History has taught us that market bottoming is a multi-phase process. In phase one, the declines are sharp and fast and typically conclude amid extreme volatility, persistent selling, and a collapse in sentiment. Sound familiar? Phase two is a retracement rally, such as the one the markets are currently experiencing. Phase three is often a retest of the earlier low.

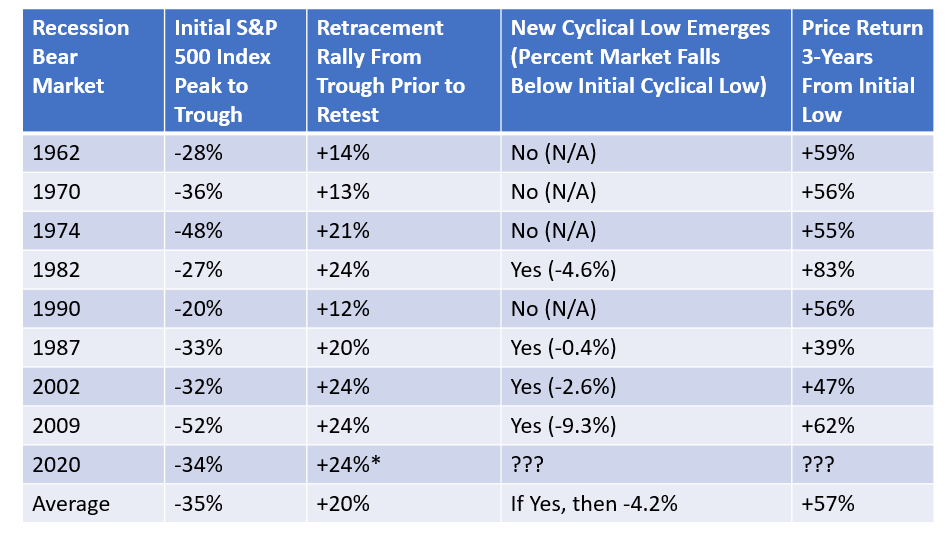

Now, you may naturally ask has a retesting of the market low historically resulted in a new cyclical market bottom? It depends. To be candid, observing market charts and choosing initial bottoms, retracement periods and retests is a bit like a Rorschach test – open for interpretation. We observed eight recession bear markets (1962, 1970, 1974, 1982, 1987, 1990, 2002, 2008). In half the instances (1962, 1970, 1974, and 1990) the initial low proved to be the cyclical low.3 In the other half of the examples (1982, 1987, 2002, and 2009), the initial low did not hold.4

The 50/50 result was somewhat unsatisfying, but it does suggest a new market low in this cycle is not a foregone conclusion. Further, it indicates a second negative catalyst, after the initial one, might be needed to drive markets lower. For example, in 2008, the perceived lack of urgency by U.S. fiscal and monetary policymakers in the initial aftermath of the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy caused markets to breach earlier lows.5 Events in 1990 add further proof to the hypothesis by demonstrating what happened when a second negative catalyst did not emerge. The recession of 1990, initially caused by central banks’ restrictive monetary policy in response to inflation concerns, was modest and short-lived. Without another negative catalyst, the initial bottom was not subsequently matched or exceeded.6

Figure 1: U.S. stock returns in the three years after an initial low in recession bear markets

Source: Bloomberg L.P. All data are represented by the S&P 500 Index* – as of April 27, 2020. Performance quoted is past performance and cannot guarantee comparable future results.

Regardless of the concerns investors often register about whether markets will retest lows, history suggests whether that happened or not had little impact on returns over the subsequent years. The average three-year market return from the initial low in the instances when that low held (1962, 1970, 1974, and 1990) was 56.5%.7 Surprisingly, when that initial low did not hold (1982, 1987, 2002, and 2009),the average three-year market return after the initial low was even better: 57.8%.8

Historically, at least, it has not mattered whether the initial low held or not. So, maybe it is time for investors to stop collectively obsessing over whether or not markets will retest lows.

Of course, there is no guarantee history will repeat itself. But the past may give one confidence in that oft-quoted observation that it’s difficult to predict the direction of the next hundred points in the S&P 500 Index, but you can be more assured in guessing what the intermediate and long-term direction of the next thousand points will be.

This post was first published at the official blog of Invesco Canada.