by Sonal Desai, Ph.D., Franklin Templeton Investments

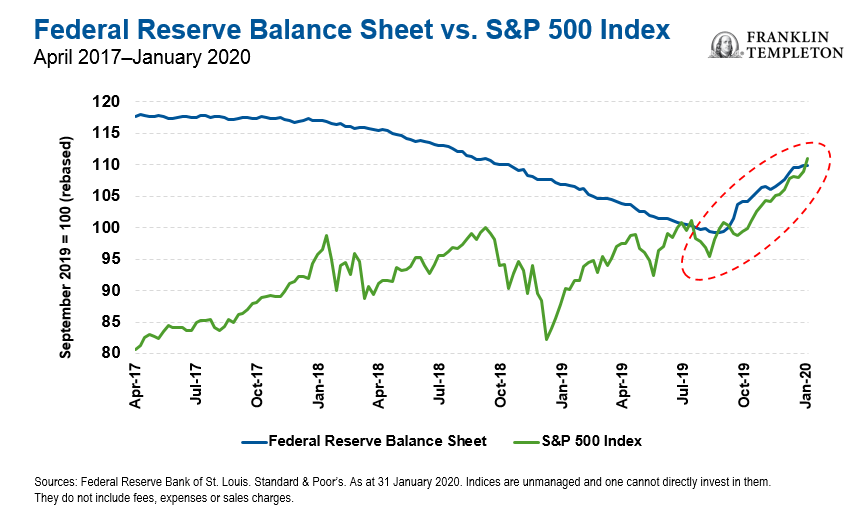

The Federal Reserve (Fed) has expanded its balance sheet by about US$400 billion since last September. This has reversed more than half of the balance sheet unwinding (about US$700 billion) which the Fed had started in October 2017.1 A growing number of analysts and investors have concluded that the Fed is once again engaged in quantitative easing (QE). The Fed denies it.

Since the facts and numbers are not in question, does it matter what we call it? As I argue below, whether we call it QE or not is largely semantics; but its impact and what it tells us about the Fed’s priorities is substance—and it matters from an investment perspective.

A Brief History of Stress

Last September, repo markets2 suffered a bout of stress triggered by a sudden liquidity crunch, which caused repo rates to spike and the Fed’s policy rate (the fed funds rate) to settle briefly above its target range.

That sent shivers down some investors’ spines: A similar episode during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) just over a decade ago reflected eroded confidence in the financial system: banks were faced with a sudden surge in uncertainty on the value of a wide range of assets as well as on counterparty risk. They reacted by hoarding liquidity.

Last fall, though, things were different; the liquidity crunch was driven by a confluence of several technical factors. First, large quarterly corporate tax payments were a major source of the stress, as corporates drew down bank balances to pay the Internal Revenue Service. This mechanically reduced the level of reserves in the banking system, while increasing the balance in the Treasury General Account. Second, non-banks (primary dealers) needed additional financing for Treasury coupon settlements.

Bank reserves had already experienced a steady decline, from about US$2.2 trillion at end-2017 to about US$1.4-$1.5 trillion in the first half of 2019.3 This was partly driven by the Fed’s shrinking balance sheet, but it also reflected banks’ redeployment of cash towards extending credit and buying securities.

Surprise!

The September crunch brought excess reserves down to US$1.3 trillion.4 This seemed still abundant. The Fed and most analysts had estimated that US$1.2-$1.3 trillion in reserves would be enough to keep the system on an even keel.

But in the aftermath of the GFC, banks face a number of new regulatory requirements: The Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) requires them to hold enough High-Quality Liquid Assets (HQLA) that can be quickly and easily liquidated to cover cash needs for a 30-day stress scenario. HQLA include not just reserves, but also Treasuries, Mortgage-Backed Securities and non-Government Sponsored Enterprise (GSE) agency debt.

However, it turns out that banks have a marked preference for meeting the LCR with reserves rather than Treasuries. This should not be surprising: Last September, banks’ excess reserves were remunerated at 2.1%, while the yield on 10-year Treasuries was below 2%; the interest on reserves has now dropped to 1.55%, which is below the 10-year Treasury yield, but not by much.5 In other words, excess reserves yield almost as much as US Treasuries, with no duration6 or liquidity risk. Clearly, the optimal basket meeting LCR requirements balancing liquidity and yield can change depending on curve shapes and spreads.

In addition, Globally Systemically Important Banks (G-SIB) have to satisfy capital buffer requirements, which depend on several factors including their interconnectedness with other financial institutions and the size of their balance sheet. This G-SIB buffer requirement is assessed on an annual basis, leading affected banks to adjust their activities in the fourth quarter to avoid a more stringent requirement. Reducing secured funding activity on the interbank market helps on this front, so this might have added to the repo-market stress.

The bottom line is that a one-off reduction in reserves because of corporate tax payments pushed banks to scramble for reserves to make sure they could comfortably meet regulatory requirements—and repo rates spiked.

The fact that this came as such a surprise to everyone, including most importantly, the Fed, should concern us.

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, central banks have deployed extraordinary monetary policy measures and enacted new regulations. They expressed confidence that they could normalise policy in a smooth and controlled manner. But last September the Fed was suddenly surprised by the amount of excess reserves that banks needed to comply with the Fed’s own regulatory requirements. This suggests that policymakers have not fully appreciated the impact of new regulations and the way they impact the conduct of monetary policy.

It Looks Like QE, Quacks Like QE…

The Fed promptly stepped in and launched a new round of Treasury bill purchases—about US$60 billion per month—to boost the level of reserves in the banking system. The Fed also raised the minimum size of its overnight repo operations to US$120 billion (from about US$75 billion). The new asset purchases are on top of the roughly US$20 billion per month that the Fed was already purchasing to offset redemptions of Mortgage-Backed Securities in its portfolio.7

Many market participants say that unwinding the unwinding of QE is, well, QE—a double negative equals a positive.

The Fed disagrees. It argues the new purchases aim at keeping short-term interest rates stable and broadly in line with the policy fed funds rate, not at easing financial conditions by driving yields on safe assets sharply lower. A technical intervention, not a new wave of policy easing. Moreover, the new purchases are concentrated on short-term maturities (12 months or less), emphasising the short-term nature of the operation.

That’s all well and good. The impact, however, has been indistinguishable from that of QE (“observationally equivalent”, as an economist would say).

The original QE aimed at lowering yields on safe assets and pushing investors into risky assets.

Since the new purchases were launched, equity prices have surged, with a disturbingly close correlation to the Fed’s balance sheet expansion; meanwhile, 10-year Treasury yields have been held below 2% even as labour markets went from strength to strength and uncertainty about trade and global growth abated.8

Why It Matters

Last year, the Fed pivoted and cut interest rates under pressure from equity markets; then stock prices surged in perfect correlation with the renewed expansion of the central bank’s balance sheet. It looks to me like the Fed has become overly dependent on markets, and markets overly dependent on the Fed.

Banks’ excess reserves have recovered to US$1.5 trillion as at last December; we should be close to the level where the banking system can handle quarterly tax payments swings without the repo market going haywire.

But now equity markets might have gotten hooked on central bank liquidity again, and they probably expect that if stock prices sag, the Fed will ease policy again like it did last year.

Some argue that this is a perception problem: Because markets believe the Fed is now engaged in QE, if the Fed stops buying assets, they will mistake it as a policy tightening.

I don’t think it’s just perception—expanding the Fed’s balance sheet has an actual impact, just as it did when the Fed called it QE.

With the US economy running at a healthy pace, labour markets going from strength to strength, and inflation close to target, the Fed’s interest rate cuts and asset purchases in the second half of last year resulted mostly in higher asset prices, especially for risky assets. The Fed has openly worried that it will have less room for policy action when the next economic downturn comes. But letting the monetary stance become captive to asset prices reduces that policy room even more.

Moreover, the fact that repo-market stress came as a surprise raises concern on what other “unknown unknowns” lie in the nexus of new regulations and what seems to be a permanently loose monetary policy stance.

This is another source of uncertainty and potential volatility to add an already rich list—and another reason, in my view, to carefully consider portfolio allocation strategies. With the Fed still adding liquidity, it pays to maintain exposure to segments of the credit market. Given the higher risk of volatility and market corrections flagged above, however, in my view investors should be especially selective in their risk exposure and maintain some “dry powder” in liquid assets to deploy when bouts of volatility provide more attractive buying opportunities.

Important Legal Information

This material reflects the analysis and opinions of the authors as at 23 January 2020, and may differ from the opinions of other portfolio managers, investment teams or platforms at Franklin Templeton. It is intended to be of general interest only and should not be construed as individual investment advice or a recommendation or solicitation to buy, sell or hold any security or to adopt any investment strategy. It does not constitute legal or tax advice.

The views expressed and the comments, opinions and analyses are rendered as at the publication date and may change without notice. The information provided in this material is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region or market, industry or strategy. The views expressed are those of the investment manager and the comments, opinions and analyses are rendered as of the publication date and may change without notice. The information provided in this material is not intended as a complete analysis of every material fact regarding any country, region or market.

All investments involve risks, including possible loss of principal.

Data from third party sources may have been used in the preparation of this material and Franklin Templeton (FT) has not independently verified, validated or audited such data. FT accepts no liability whatsoever for any loss arising from use of this information and reliance upon the comments opinions and analyses in the material is at the sole discretion of the user.

Products, services and information may not be available in all jurisdictions and are offered outside the US by other FT affiliates and/or their distributors as local laws and regulation permits. Please consult your own professional adviser or Franklin Templeton institutional contact for further information on availability of products and services in your jurisdiction.

What Are the Risks?

All investments involve risk, including possible loss of principal. The value of investments can go down as well as up, and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Bond prices generally move in the opposite direction of interest rates. Thus, as prices of bonds in an investment portfolio adjust to a rise in interest rates, the value of the portfolio may decline. Changes in the financial strength of a bond issuer or in a bond’s credit rating may affect its value. Investments in foreign securities involve special risks including currency fluctuations, economic instability and political developments. Investments in emerging market countries involve heightened risks related to the same factors, in addition to those associated with these markets’ smaller size, lesser liquidity and lack of established legal, political, business and social frameworks to support securities markets. Such investments could experience significant price volatility in any given year. High yields reflect the higher credit risk associated with these lower-rated securities and, in some cases, the lower market prices for these instruments. Interest rate movements may affect the share price and yield. Stock prices fluctuate, sometimes rapidly and dramatically, due to factors affecting individual companies, particular industries or sectors, or general market conditions. Treasuries, if held to maturity, offer a fixed rate of return and fixed principal value; their interest payments and principal are guaranteed.

For timely investing tidbits, follow us on Twitter @FTI_Global and on LinkedIn.

_______________________________

1. Source: Federal Reserve. As at 31 December 2019.

2. The repo market refers to repurchase agreements, a type of short-term borrowing for dealers in government securities.

3. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Recession periods as indicated by the National Bureau of Economic Research. As at 31 December 2019.

4. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Recession periods as indicated by the National Bureau of Economic Research. As at 31 December 2019.

5. Sources: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Bloomberg. As at 13 January 2020.

6. Duration is a measure of the sensitivity of a bond or a fund to changes in interest rates. It is typically expressed in years.

7. Source: Federal Reserve Bank of New York. As at 13 January 2020.

8. Source: Federal Reserve. As at 13 January 2020.

This post was first published at the official blog of Franklin Templeton Investments.