by Seth Levine, The Integrating Investor

I always find this time of year to be self-reflective. Year-end provides a natural point for critiquing past performance and fitting it into a broader investing context. These holidays in particular have a way of foisting this perspective upon me, and with deep meaning. As a parent of two young kids, my holidays now kick off with Halloween. Perhaps stuck in this spirit, I find myself wondering: Why are we so scared?

I can’t seem to shake this sense that we live in a culture that’s scared. I see a number of signs across the economic, political, and investment landscapes that seem support this observation. To be sure, this is not universally true on an individual level. However, as a culture we seem to have lost our mojo, our swagger, and the confidence that fuels significant economic advancements.

Why Scared

Scared is psychological state. It connotes being afraid or frightened. Scared feelings typically arise when one feels helpless in a situation or believes he/she is unable to improve it via action. Thus, it’s closely associated with victimhood. Scared is not a feeling that accompanies independence, confidence, and capability.

By all accounts this is the best time in human history to be alive. It’s never been easier to access information, collaborators, and different perspectives, nor in such abundance. These conditions should enable self-reliance and wealth creation. They are a perfect crucible for unbounded development and prosperity.

Yet, economic independence doesn’t seem as valued today as it once was. The cultural impetus shies away from proximal challenges and looks to others for solutions—and in particular, for political solutions. This doesn’t square with the times.

In my view, this shift is a matter of confidence and self-esteem. It’s not the shirking of responsibility that’s telling; it’s the unwillingness to engage with the issues. Confident individuals face challenges head-on. Scared ones look to others. Problem solving often requires creativity, not reverting to staid and ineffective ideas. The former is a strength of the market; the latter is a politician’s. To be sure, there’s a time and place for politicians and bureaucrats to assist. However, economics is not the place and these are not the times. The obsession with finding political fixes for economic underperformance suggests to me that we lack the self-confidence to tackle it ourselves. We seem scared.

Central Bank Dependence

The clearest example of this in the investment markets is the neurotic obsession with central banks. I commonly hear people critique their ignorance and ineffectiveness only to follow with—the same people, mind you—what central bankers ought to do next. I thought central bankers were ineffective?

It’s time we stop looking to central banks for solutions. They don’t have them. In fact, I see no need for them at all. In theory, central banks were created to oversee the money supply. Dual mandates were afterthoughts. Since the money supply merely reflects economic activity, this should be a fairly mundane task and one that decentralized private banking centers performed quite well (despite the popular narrative).

* WILLIAMS SAYS FED WOULD ADDRESS NEXT RECESSION BY CUTTING INTEREST RATES TO ZERO AND USING COMMUNICATION AND ASSET PURCHASES

(via @reuters)

— Carl Quintanilla (@carlquintanilla) November 6, 2019

Today, however, our opinions of central bankers are quite different. They are viewed as omniscient, economic alchemists. We look to central bankers to manipulate business cycles, control inflation, and prescribe prosperous economic conditions. Where did this come from and when did it become so prevalent? Central banks can’t create money let alone produce these other conditions. They fall under the purview of the productive economy and thus are products of our actions alone. The perception of central bank dependence is false and marginalizes our own economic efficacies.

Political Dependence

The central bank obsession is, in my view, part of the more general, cultural shift towards increased political dependence. This can be observed by the rise of populism writ large. From Trump’s presidency in the U.S., to Brexit, to the Five Star Party in Italy, to the yellow-vest movement in France, there’s a clamor for retrenchment within national borders. The U.S.-China trade war is just another iteration of this, justified rationalized or not.

To me, there’s a common theme to these movements. They are indicative of a reversion to tribalism, the cutting of global ties that underpin modern day prosperity, and represent a fear of “the other” mentality common in all primitive and destructive cultures.

Why is it important where the human who produced your steel resides? Seriously, why does it matter to you? If that person’s so evil the solution is simple: deal with someone else. I promise you there is no greater commercial influence than that. Just put yourself in the shoes of a business owner to see (go ahead, close your eyes and imagine).

Why are we suddenly seeking politicians to protect us from the ever-changing world? Economic issues are those of voluntary exchange and they are dynamic. Very few problems require political fixes. Seeking them indicates that one is too scared to trust his/her actions. It’s a skepticism over the power one commands in the marketplace. It’s cowardly.

The Monetary Policy—Fiscal Policy False Dichotomy

It’s often helpful to compare and contrast ideas against extreme conditions. Doing so can surface the essential issues for easier analysis. This is especially true for complex concepts such as those found in economics. Oftentimes, impacts are not obvious and secondary and tertiary effects must be considered.

In the investment markets we often hear about fiscal or monetary policy initiatives. Whenever the economy needs a boost, commentators opine that more accommodative monetary policy might be needed (such as lower interest rates). Or perhaps this particular instance requires a fiscal policy response (like lower taxes and/or greater government spending). Whatever the case may be, prescriptions are framed as being a matter of monetary policy or fiscal policy initiatives.

Nothing, in my view, illustrates cultural fear more than this false dichotomy of monetary policy—fiscal policy. They are conceptually similar and not appropriate book-ends of a conceptual dichotomy. Rather, monetary and fiscal policies are different flavors of central planning. Both seek government intervention in the economy, differing only by their preferred branch. Monetary policy utilizes central bank action while fiscal policy seeks legislative cures. They are not opposites.

The true opposite to central planning is economic liberty. Thus, the proper spectrum, in my view, has economic freedom on one side (deregulation and less controls) and central planning—i.e. fiscal and monetary policy, which are greater controls—on the other. One side reflects independence and confidence while the other forceful paternal shelter. Considering monetary or fiscal policy actions only rejects self-reliance as an option altogether. It’s a scared perspective.

Pacifying Investment Decisions

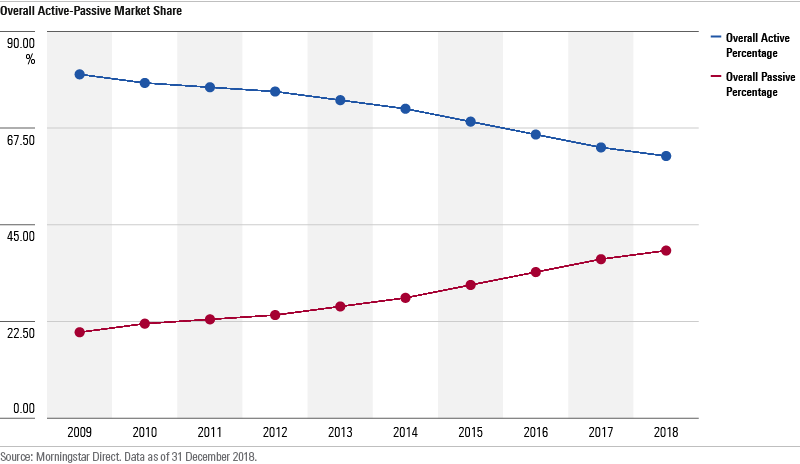

I also see the shift to passive investment strategies to fit into the fear of independence theme. To be sure, there are virtues of passive investing. Track records and fees relative to active management are compelling enough. But are these the sole motives?

What if a fear of underperforming popular indices or standing out plays a part? Speculating on the future often yields wrong outcomes; it’s part and parcel with investing. As a colleague of mine is fond of saying, “we’re not bootstrapping treasuries.” By this he means that earning returns requires taking risks. Sometimes things don’t pan out as planned and losses occur. The trick, of course, is to minimize the losses; not neurotically seek to avoid them.

Are allocators more concerned with finding the comfort of consultants’ consensus rather than investing according to their own observations? Could career risk play a part in this trend? Are we too scared of being wrong to invest in themes that might play out over longer time horizons?

Share Buybacks Are Safest

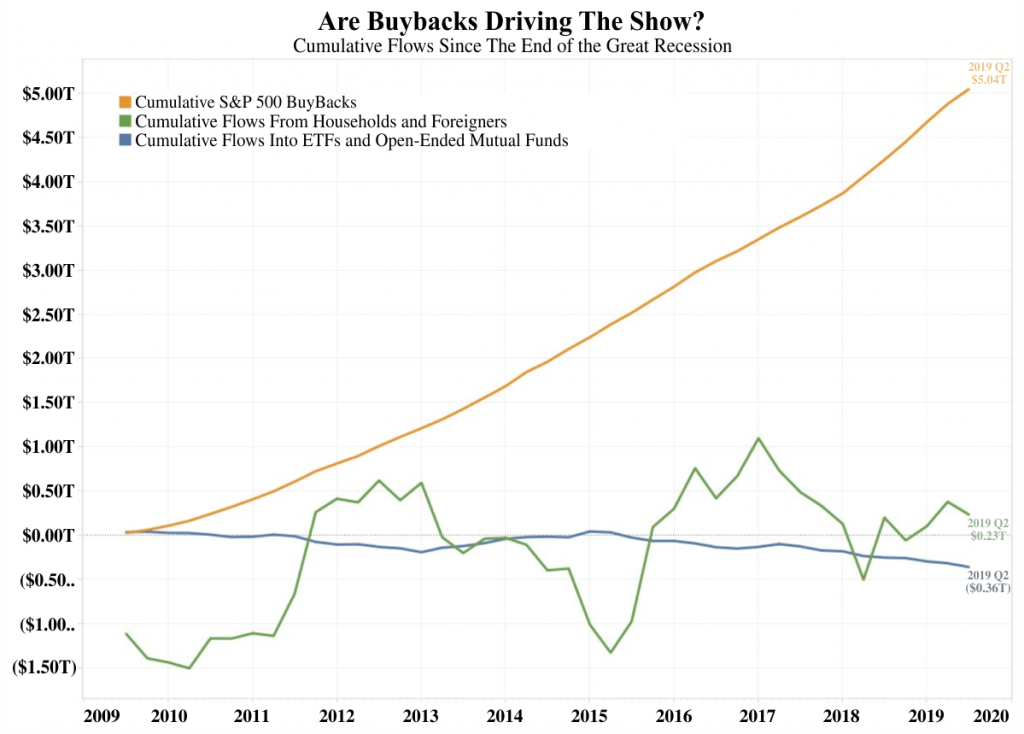

What about share buybacks? Much has been made about the magnitude at which corporations have repurchased their shares. Why is this happening at such an unusually high level?

To be sure, I take no issue with share repurchases and see them as a legitimate use of capital. However, even accretive buy-backs have short-lived impacts. They last only a year when year-over-year comparisons are made. Why aren’t businesses investing in projects that could yield multi-year benefits? Are executives simply playing it safe, too scared to commit capital to projects that might fail? Are the majority of shareholders really so shortsighted?

Scared As An Investment Theme

It’s easy to roll your eyes at this article and dismiss it as another meme. However, my intention is neither to seek scapegoats nor to emotionally vent. Rather, I’m interested in exploring whether this behavior is part of a larger cultural phenomenon of fear. If so, the next downturn could push us further from economic liberty and more towards political controls. This would surely have investment implications.

Of course, there is no such thing as “we.” We is just an aggregation of “I’s.” Thus the real question is: Why am I so scared? While an uncomfortable, if not antagonistic question to ask, it’s critical to understanding this emergent theme.

The world is in constant flux. No one should appreciate this more than investors. Change is the essence of our jobs—to profit from the movements in asset prices. Prices don’t move in stagnant conditions.

Yet, as a culture we seem terrified by change. I find this puzzling since we’ve never been better equipped to adapt and capitalize from it. Those investors who embrace change will survive and thrive. Those who don’t could perish from this business. What could be scarier than that?

Copyright © The Integrating Investor