by Kristina Hooper, Invesco Canada

On Dec. 12, the U.K. is holding a general election, and the outcome is difficult to gauge. While the Conservative and Labour parties try to broaden the debate, the dominant theme remains Brexit. To give us a preview of this important election, I’m turning over today’s Weekly Market Compass blog to my colleague Paul Jackson. Paul is based in our London office and has been tracking the election news and polls closely.

Paul Jackson: Thank you, Kristina. Through this election, U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson is trying to win a mandate that will enable him to gain Parliamentary approval for his European Union (EU) withdrawal agreement. If he is successful, the U.K. would in theory leave the EU by Jan. 31, 2020, thus launching a process to negotiate the future trade arrangement between the U.K. and EU. We believe that such an outcome is largely priced into U.K. financial markets.

A quick glance at recent polls would suggest that Johnson has a good chance of realizing that plan. His Conservative Party has been well ahead of Labour in the opinion polls (39% versus 28% based on the average of the 10 most recent opinion polls).1 However, it should be remembered that Theresa May started the 2017 election campaign with an even bigger lead, only to see the gap closed.

There are two main ways in which Johnson’s “orderly” Brexit could be derailed:

- If the sum of Conservative Party and Brexit Party Parliamentary seats is so large that it tilts Westminster into “hard-Brexit” territory (or the Brexit Party becomes the swing party), a no-deal outcome may win the day.

- If Labour wins or (more likely) there is a hung Parliament, the only solution may be to have a second referendum.

We suspect the first outcome would damage sterling while depressing gilt yields and, probably, U.K. equities (especially those with a domestic U.K. orientation). On the other hand, we believe the prospect of a second referendum (and the prospect of no Brexit) would be good for sterling and U.K. equities (pending the outcome of the vote).

Polls indicate a gain for Conservatives

This is a difficult election to call with many moving parts. Members of Parliament (MPs) have been standing down or switching parties, various alliances have been formed between parties, and voters have been ignoring traditional party allegiances in order to express their Brexit preference. But while it’s impossible to predict the outcome with 100% certainty, we can gain important clues from analyzing polls, party alliances, and history.

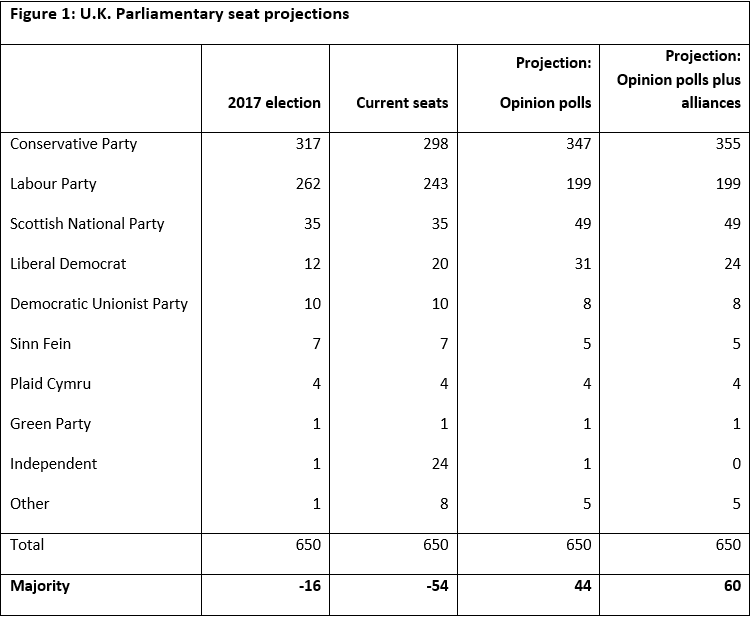

Figure 1 shows the results of our constituency-by-constituency analysis, using regional swing factors in play since the 2017 election. Based on recent opinion polls, this methodology suggests the Conservative Party may gain 49 seats on top of its current 298 (reaching a total of 347), and that Labour may lose 44 seats, falling to a total of 199. (The Brexit Party would continue to have no seats in our analysis.) This would be enough to give a Conservative majority of 44, which we estimate would be enough to get Johnson’s EU withdrawal agreement through the U.K. Parliament and for the U.K. to leave the EU on or before Jan. 31, 2020.

However, there are two alliances that could change the outcome, given the U.K.’s voting system. The “Remain Alliance” between Liberal Democrats, the Green Party, and Plaid Cymru covers 60 seats in England and Wales, but our analysis suggests it could have a limited effect. However, the decision by the Brexit Party to not stand in constituencies won by the Conservatives in 2017 (which we are classifying as an “alliance”) could add seats for the Conservative Party, largely at the expense of the Liberal Democrats. We are assuming the Brexit Party continues to have no MPs after the election.

The upshot — illustrated in the last column of Figure 1 — could be a 60-seat majority for the Conservatives, which we believe would be enough to get Brexit done, or at least the first part of it.

Sources: BMG, Savanta ComRes, Deltapoll, Hanbury, ICM, IPSOS MORI, Kantar, Number Cruncher Politics, One Poll, Opinium, Panelbase, Populus, Sky Data, Survation, YouGov, Wikipedia, and Invesco. Notes: Using the 2017 general election result as the starting point, the “opinion polls” projection is made by applying regional voting swing factors. The House Speaker is included in the “Other” category and not within their party’s count. “Opinion polls plus alliances” assumes the following: for the “Remain Alliance,” the votes for the Liberal Democrats, Greens, and Plaid Cymru are aggregated in favor of the party that has been nominated to fight the given constituency (the agreement covers 60 constituencies); for those constituencies won by the Conservative Party in 2017 (where the Brexit Party has said it will not present a candidate), the Brexit Party vote is now split between Conservatives and Labour in proportion to the votes received in 2017. There is no guarantee the projections mentioned will come to pass.

The election is just the beginning

We believe the U.K. financial markets would experience relief if Brexit gets done with an agreement. However, even with an agreement, the real work would start when negotiating the future U.K.-EU relationship. Hence, any market relief may be short-lived as Johnson has said the transition period would not extend beyond 2020, which we believe is totally unrealistic. Rather, we believe the negotiation of a future trade deal with the EU would likely take far longer, and something will have to give — either the deadline could get extended or the U.K. could leave the EU with no deal at the end of the transition period. Yes, a no-deal Brexit is still possible.

Hence, what appears to be relatively good news as 2019 draws to a close (an orderly Brexit) could turn to angst during 2020 as the real negotiations begin against the backdrop of an unrealistic timetable. We believe the good news is now largely priced into U.K. financial markets (sterling has recovered over recent months, for example) and suspect that 2020 will see the return of volatility, especially if Scotland pushes for an independence referendum and pressure grows in Northern Ireland for reunification with Eire (both Scotland and Northern Ireland voted to stay in the EU).

Caution is required, of course, as the mood among U.K. voters can change during the election campaign (as it did in 2017) and opinion polls may be a less-than-perfect guide (as we have seen in many countries). However, it would take quite some change for the Conservatives not to win a majority.

This post was first published at the official blog of Invesco Canada.