by Hubert Marleau, Chief Investment Strategist, Palos Management

It appears that the U.S. and China have agreed on a so-called “ Phase One” of a trade deal. They had to come up with something that would immediately arrest or at least decrease the odds of what could have been a significant escalation in trade tensions and give hope that a framework for a more detailed agreement is in place.

The market had had enough and wanted at least some sign of a reduction in provocative exchanges. Whilst, the things that were agreed upon like the foreign exchange agreement, the agricultural purchases and the hold on scheduled tariff increases are great, the paw-how did not resolve the main issues behind the trade tensions. i.e. China’s intellectual property theft, technology transfers and industrial subsidies.

Although scant on details, it shows that President Trump, facing an election and under pressure, does not want to ratchet up trade tensions. JPMorgan sent a reminder to their clients on Friday saying that “investors should be aware that global growth usually rebounds from shocks that don’t culminate in recessions--like the 1997-98 Asian crisis, 2012-12 eurozone crisis and the 2015-16 emerging market credit crunch.” As a matter of fact, subsequent rebounds can be sharp and enduring. Take a look at the yield curve--it’s positive.

Thus, the new “U.S.-Sino Accord” will allow investors to look at other matters of great concern. We are living in an era of profound change and uncertainty. Yet, investors want economists to provide simple answers to complex questions. Two big questions need to be answered. That is whether inflation has ended and are low interest rates permanent.

The “Economist” wrote a cover story on the weekend wondering if inflation has ended. The article makes reference to a special IMF report which will likely argue that inflation expectations are anchored because of technological change and the flow of goods and capital across borders conspiring to make inflation less meaningful. Thus, it has become extremely difficult for central banks to hit their inflation targets. In terms of GDP, the “Economist” showed that 91% of the inflation-targeting world is an inflation laggard.

A jumble of forces from globalization to technology to demographics has disrupted conventional economic thinking to the point that central banks and politicians believe that the risk of inflation shortfalls loom larger than that of excessive price rises. Consequently, they are willing and ready to dispense with orthodoxy, change their conventional ways, and adopt new bold policies which fit what is popular with the left and right wings of populism. In populist terms, it’s not about growing the pie, but slicing it up. The populists are playing a blame game that is winning hands down.

On the fiscal side, simple prescriptions to reduce wealth and income inequalities are being introduced like shutting out immigrants, taxing the millionaires, raising entitlements etc. These ideas will likely be legislated soon. On the monetary side, elementary ideas like “MMT” (to fund government deficits) and “Helicopter Money” (to beef up consumer spending) are being proposed by a growing body of freethinkers and pushed by many government policy makers.

On the trade side, protectionist tariffs which contract output, and therefore supply. I do not see anything at the moment that will stem the tides of change. The arguments are that 1) deficits and public debt are sustainable because interest rates are either very low or negative and 2) inequality is causing a primary problem on the demand side. A price change is a signal. Falling prices mean either an abundance of supply or a lack of demand. The IMF has joined the parade.

The new IMF managing director, Kristalina Georgieva, believes that a reset is required like in the 1970s supporting the concept that it is ok for governments to borrow more in order to assure global demand is sufficient to starve secular stagnation. The thing is that the policy makers have the power to restore inflation. What it takes is willingness to do what is necessary. There are examples where drastic measures were taken in the past to achieve objectives. In the 1930’s Roosevelt introduced a revolutionary new deal to revive the economy and in the 1980s Paul Volker ostensibly freed up interest rates and targeted the money supply to kill inflation.

Unfortunately, the growing adoption of strikingly simplistic explanations and economic measures which the general population easily eats up, present a clear danger for investors who do not recognize the unintended consequences that the above ideas and actions may have on eventual inflation. I do not care what anyone says, it’s a law of economics that if taxes are cut for the middle class or if money is made available to people at large from bank reserves to spur spending and interest rates are kept low with the help of the printing press to fund budget deficits, some currency debasement will eventually come.

The movement of rearranging the division of responsibility between central banks and governments to bring about a meaningful reduction in inequality will produce over time two inflationary effects. It will increase the propensity to spend and reduce the tendency to save. In themselves, these tendencies may not be good over the long term, but they are clearly inflationary.

The understanding that central banks are likely to be very tolerant to political pressure or just think that it would be expedient to allow the inflation rate to cross the 2% mark, demands the

attention of investors who take a long term view. In this respect, investors should carefully shy away from interest rate sensitive investments and slowly load up with price sensitive assets.

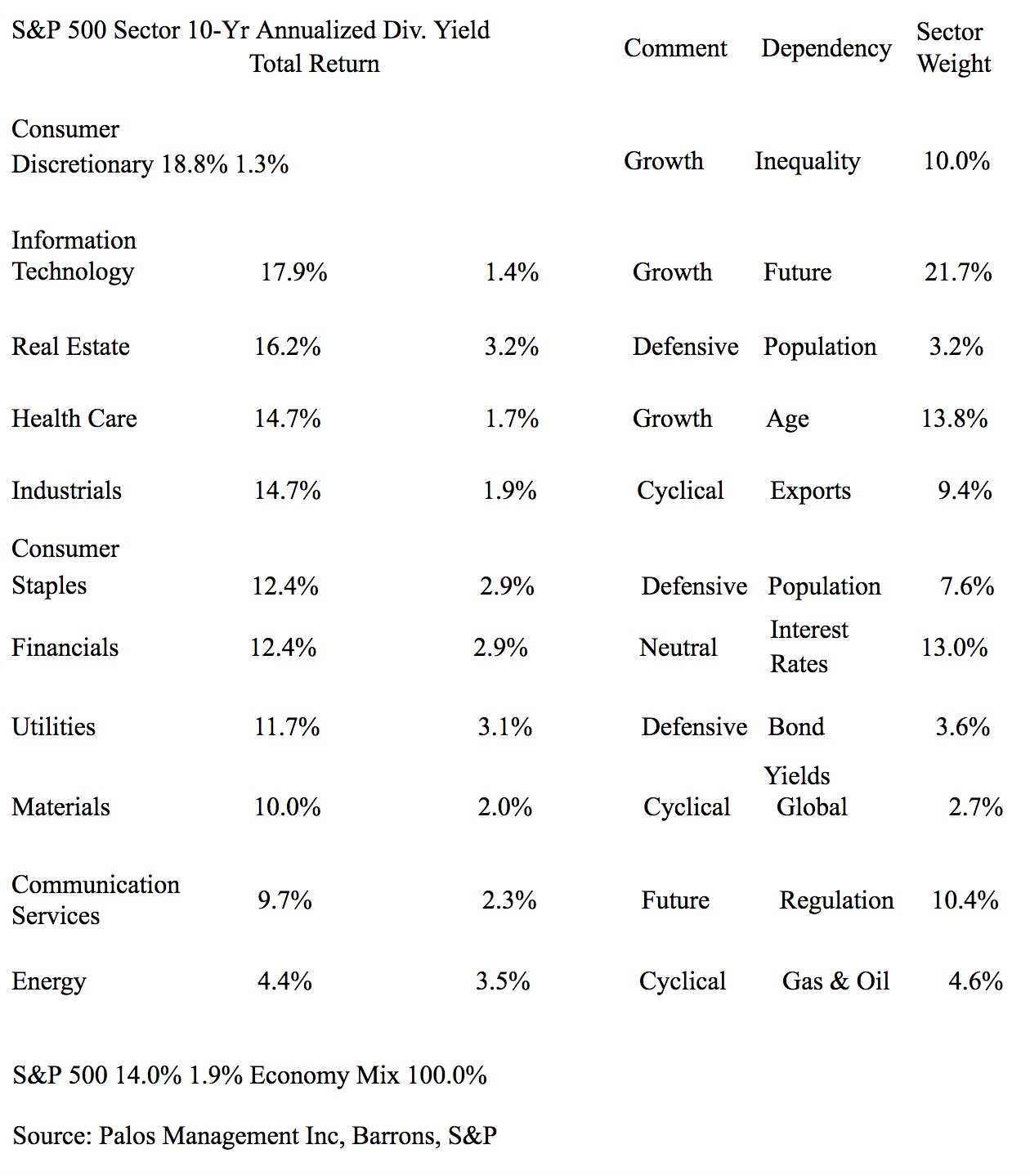

Looking at the 11 Sectors of the S&P 500 by the Numbers:

Copyright © Palos Management