by Mike Pyle, Blackrock

Mike explains why we have decided to upgrade our call on European assets, from equities to government bonds.

We see the European Central Bank (ECB) shifting decisively dovish in coming months, against the backdrop of stabilizing growth outlook and persistent inflation undershoots. This is the main reason that has prompted us to close our underweight call on both European equities and credit, and to upgrade European government bonds.

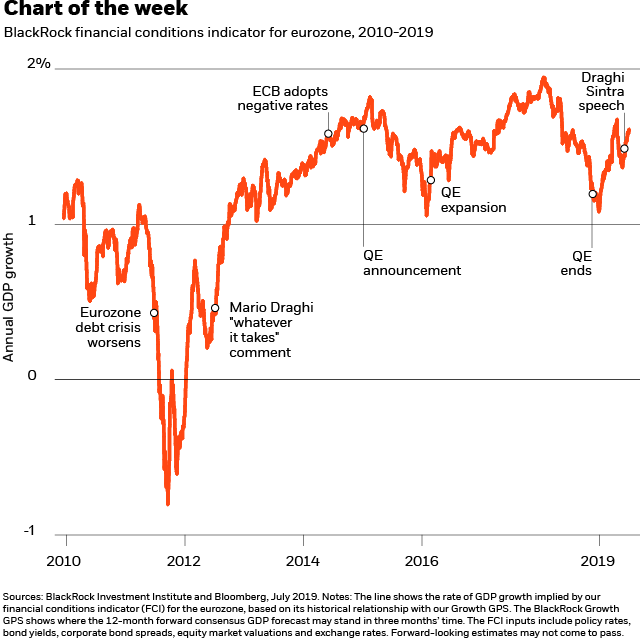

Eurozone financial conditions, as measured by our financial conditions indicator (FCI) in the chart above, have already improved. Importantly, the ECB is likely to announce new stimulus in the coming months in an effort to lift stubbornly low inflation. The package we expect is not yet fully reflected in markets, in our view, and should help further ease financial conditions and support European assets. The ECB may outline its thinking at this week’s policy meeting and take action later in the year. Measures could include further cuts to its already negative 0.4% deposit rate and a new round of purchases of financial assets including corporate bonds.

A benign environment for now

We have recently downgraded our global growth outlook as trade and geopolitical tensions are stoking macro uncertainty. The growth outlook has weakened primarily in the U.S. and China recently, but steadied in the eurozone albeit at below-trend levels. The decisively dovish shift by central banks should make for a relatively benign environment for risk assets in the near term. China’s growth looks to stabilize as policymakers stand ready with additional fiscal stimulus, easing concerns about a potential drag on the European economy.

The easing we expect the ECB to deliver is not yet fully reflected in markets, we believe. This has prompted us to upgrade European government bonds to overweight and close our underweight in equities and credit. In government debt, we expect peripherals, or government bonds of mostly southern-tier countries, to benefit most from the fresh stimulus. A “lower for longer” environment should support credit as a source of income in a region where many government bond yields of core countries are negative. We favor high yield corporates for their muted issuance, strong inflows and spread premium to U.S. counterparts.

Our ECB view supports closing the underweight in European equities. European equity funds have seen the longest stretch of outflows in 10 years, according to EPFR data, meaning many investors are under-invested in the region. Earnings expectations have largely priced in risks of slower growth, and we see potential for an earnings rebound next year. Equity risk premia (the expected return advantage of holding equities over government bonds) in Europe are now similar to those of riskier emerging markets. We prefer the quality factor and defensive sectors that feature high profitability, stable earnings and low indebtedness, such as pharmaceuticals. We like companies with sustainable and relatively high dividend yields. These stocks, as well as European high yield credit and peripherals, are particularly attractive for hedged U.S. dollar-based investors because of the hefty U.S.-euro interest rate differential. We generally dislike the consumer discretionary sector due to its vulnerability to trade conflicts, and avoid banks given negative rates.

Mike Pyle is BlackRock’s global chief investment strategist. He is a regular contributor to The Blog

Investing involves risks, including possible loss of principal.

This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research or investment advice, and is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any investment strategy. The opinions expressed are as of July 2019 and may change as subsequent conditions vary. The information and opinions contained in this post are derived from proprietary and non-proprietary sources deemed by BlackRock to be reliable, are not necessarily all-inclusive and are not guaranteed as to accuracy. As such, no warranty of accuracy or reliability is given and no responsibility arising in any other way for errors and omissions (including responsibility to any person by reason of negligence) is accepted by BlackRock, its officers, employees or agents. This post may contain “forward-looking” information that is not purely historical in nature. Such information may include, among other things, projections and forecasts. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. Reliance upon information in this post is at the sole discretion of the reader. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Index performance is shown for illustrative purposes only. You cannot invest directly in an index.

©2019 BlackRock, Inc. All rights reserved. BLACKROCK is a registered trademark of BlackRock, Inc., or its subsidiaries in the United States and elsewhere. All other marks are the property of their respective owners.

BIIM0719U-899492

This post was first published at the official blog of Blackrock.