by Elga Bartsch, PhD, Blackrock

The Fed is considering a new policy framework to better steer inflation expectations. Elga examines the economic and market implications.

Inflation expectations have sharply fallen recently, driving down U.S. government bond yields and focusing attention on Fed policy. The market now expects three Fed rate cuts by the end of 2020. The Fed is getting concerned that its current toolkit won’t effectively counter a future recession. Hence it’s considering new strategies to boost inflation expectations, with important economic and market implications, in our view.

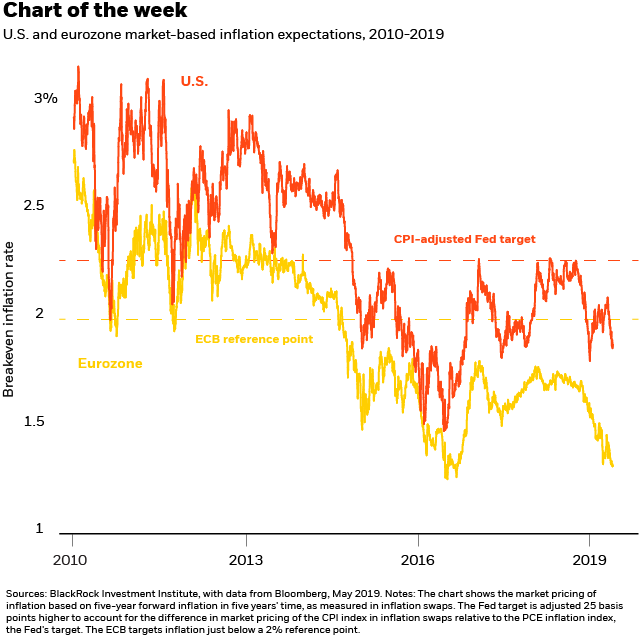

The Fed’s review could lead to policy changes early next year. It will be in focus at a Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago conference this week. The review aims to address a two-fold challenge faced by central banks since the global financial crisis: falling neutral interest rates – rates that would neither stimulate nor curtail economic growth – and falling inflation expectations. Both could diminish monetary policy’s ability to counter future downturns by reducing the distance between the actual interest rate and the lowest level of interest rates a central bank can feasibly set. The chart shows how inflation expectations have slipped meaningfully below targets after an extended period of actual inflation falling short of central bank targets. Expectations have not been as tethered to the targets as markets participants and central banks had hoped. The persistence of this trend could start to call into question the credibility of central banks’ inflation targets, in our view.

Shifting to make-up strategies

The monetary policy options the Fed and other developed market central banks are discussing include a shift from flexible inflation targeting – maintaining the inflation rate near the target – to “make-up” strategies that would deliberately allow the economy to run hot for a while to compensate for a previous inflation shortfall. We assess the implications of such a shift in our new Macro and market perspectives Fed to raise its inflation game? co-authored with Bob Miller, BlackRock’s Head of Fundamental Fixed Income – Americas, and Jonathan Pingle, Head of Economics for Global Fixed Income.

Make-up strategies – average inflation targeting is one example – require markets believe that central banks will be able to push inflation above their targets despite central banks’ current struggles to do this. Without this belief, it’s unlikely central banks could engineer the required sizable swings in inflation expectations.

The economic impact would depend on the specifics of any Fed strategy shift. But a few common themes emerge when we compare policy interest rates under flexible inflation targeting to the alternative make-up strategies being considered. Fed and academic models suggest the economy returns more quickly to a steady state following a downturn if central banks opt for make-up strategies. Interest rates would likely stay lower for longer than under the present policy framework. If the Fed had adopted a make-up strategy after the financial crisis, it would probably not yet have started to raise rates from post-crisis lows. Macroeconomic volatility could decrease as the risk of a severe economic downturn diminishes. And the risk of asset bubbles could increase.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell has said factors weighing on core U.S. inflation are “transitory.” Our Inflation GPS supports this view. We expect the Fed to keep rates on hold for an extended period, unless an unexpected escalation in trade tensions creates material risks to growth. If the Fed implements a make-up strategy, it might help reduce the risk of deflation and the risk of a recession deepening into a full-blown depression, though we believe more radical measures would be needed to deal with a recession. These reduced risks – along with lower-for-longer rates and higher long-term inflation expectations – would likely support risk assets in the near term. But any market impact may be diluted if the change is billed as a tweak to the Fed’s current framework.

Elga Bartsch, PhD, Head of Economic and Markets Research for the BlackRock Investment Institute, is a regular contributor to The Blog.

Investing involves risks, including possible loss of principal.

This material is not intended to be relied upon as a forecast, research or investment advice, and is not a recommendation, offer or solicitation to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any investment strategy. The opinions expressed are as of June 2019 and may change as subsequent conditions vary. The information and opinions contained in this post are derived from proprietary and nonproprietary sources deemed by BlackRock to be reliable, are not necessarily all-inclusive and are not guaranteed as to accuracy. As such, no warranty of accuracy or reliability is given and no responsibility arising in any other way for errors and omissions (including responsibility to any person by reason of negligence) is accepted by BlackRock, its officers, employees or agents. This post may contain “forward-looking” information that is not purely historical in nature. Such information may include, among other things, projections and forecasts. There is no guarantee that any forecasts made will come to pass. Reliance upon information in this post is at the sole discretion of the reader. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Index performance is shown for illustrative purposes only. You cannot invest directly in an index.

©2019 BlackRock, Inc. All rights reserved. BLACKROCK is a registered trademark of BlackRock, Inc., or its subsidiaries in the United States and elsewhere. All other marks are the property of their respective owners.

BIIM0619U-859359