by Liz Ann Sonders, Senior Vice President, Chief Investment Strategist, Charles Schwab & Co

Key Points

- Leaving politics out of it, if that’s possible, let’s dive into the economic implications of the trade war and tariffs; currently and prospectively.

- The United States has been bearing the brunt of the trade war’s economic impact to date.

- Escalation and implementation of the third phase of tariffs would hit consumer goods, and likely inflation, to a more significant degree than the first two phases.

Although we’ve put out short notes to our clients over the past few months about the United States-China trade war and tariffs’ impact on the economy, it’s been a while since I penned a more comprehensive (read: longer) report. We always do our best to stay out of the morass of partisan politics, and trade tends to find its way into that morass; but our job is to be objective about the economic consequences.

Tweets aren’t guarantees

Hope had become elevated alongside the U.S. stock market’s rally off last year’s December lows that a trade deal was a done deal. We were more skeptical than the consensus—not because of any particularly unique knowledge about what was happening behind the scenes, but because there were few concrete indications, other than the market’s rally and a few tweets, that a deal was all-but-inked.

Although the U.S. stock market had already rolled over from its recent peak, the early-May announcement that the latest round of tariffs on $200 billion of Chinese goods were going to be raised from 10% to 25% exacerbated the sell off and raised volatility. That announcement and China’s promise to retaliate with more tariffs on U.S. goods exported to China dented investor sentiment and the market, unleashing a pullback of more than 5% in the S&P 500 and the Dow Jones Industrial Average and more than 6% for the NASDAQ.

Last week brought some relatively better news with the Trump administration announcing it was delaying by six months the threatened imposition of auto and auto parts tariffs, which would have widened the trade war to include the European Union and Japan. In addition, tariff discussions in North America associated with the formerly-NAFTA/now-USMCA deal suggest the likelihood of Congressional ratification has increased. These newsworthy events, as well as some better news on housing and Walmart’s earnings’ beat, helped lift stocks last week.

However, later in the week it was offset by the Trump administration moving to make it more difficult for U.S. companies to do business with Huawei, one of China’s largest telecommunications companies. In response, Chinese Commerce Ministry spokesman Gao Feng said Thursday, according to state-run news agency Xinhau, that the United States is exhibiting “bullying behavior” and that it is “regrettable that the U.S. side unilaterally escalated trade disputes, which resulted in severe negotiating setbacks.” So, the battle rages on.

Longer-term look

Let’s try to escape the ultra-short-term noise and dive into the longer-term implications of the tariffs imposed to date, and those which remain prospective. Before getting to that, we should start with the basics: Tariffs are a ‘tax’ on imported goods and are paid directly by U.S. importers of Chinese goods. The tariffs are paid to the U.S. Customs & Border Protection Service at the U.S. border by a U.S. broker representing a U.S. importer. They are not paid by the Chinese to the United States.

Historically, according to our research, tariffs have resulted in higher inflation, increased policy uncertainty, weaker capital spending (capex), slower productivity growth, and less robust employment growth. Furthermore, trying to bring down the trade deficit—while last year’s fiscal stimulus raised the budget deficit—could bring tighter financial conditions (and possibly higher interest rates longer-term). In fact, after loosening from December 2018 through April of this year, financial conditions have generally been tightening so far in May according to the Bloomberg Financial Conditions Index. This is likely to continue if the strength in the U.S. dollar persists (likely if the Chinese yuan continues to depreciate) and equity market volatility remains elevated.

Tariffs’ timeline and impact

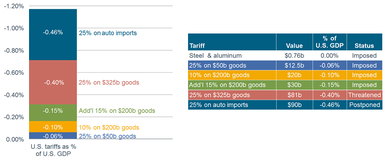

Below are two graphics—the first represents the timeline of the current roster of tariffs, while the second measures the value of those tariffs and the expected hit to U.S. gross domestic product (GDP).

Trade War Tariffs’ Timeline

Source: Charles Schwab.

Economic Impact of Tariffs

Source: Charles Schwab, Cornerstone Macro.

Although the United States and China are the key players in this game of tariffs, the impact has spread to the broader global economy—through not only the confidence channels, but also global trade volumes. As you can see in the chart below, although not (yet) in deep negative territory, there has been enough of a falloff in world trade volumes that we’re looking at a drop last seen during the Great Recession (as well as prior to that in the 2001 recession).

World Trade Slumping

Source: Charles Schwab, Bloomberg, as of February 28, 2019.

With world trade having slumped, the rebound in oil prices is an added rub as is the rising U.S. dollar; denting hopes for a capex-led next leg of the economic expansion. Even prior to the latest trade war tit-for-tat, the Philadelphia Fed’s survey of capex intentions had plunged by 45% from its October 2017 high—when optimism was at its peak courtesy of the expected corporate tax cut.

United States bearing brunt of tariffs’ pain

To date, evidence suggests that close to 100% of the tariffs in place have been borne by U.S. companies and consumers. A recent paper from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) (https://www.nber.org/digest/may19/w25638.shtml) compared prices of Chinese imports subject to the tariffs to similar non-tariffed goods. If Chinese producers had been somehow-forced to bear the cost of the tariffs, pre-tariff import prices would have declined. Instead, tariffs were absorbed by U.S. importers in the form of either lower profit margins or by U.S. consumers in the form of higher selling prices.

Just last Thursday, Walmart’s CFO Brett Biggs said, “We will do everything we can to keep prices low, but increased tariffs lead to increased prices.” More broadly, Evercore ISI’s retail analyst Greg Melich believes that tariffs are “the next key swing factor” as they could potentially “wipe out” earnings growth across the retail sector this year.

Impact on inflation

Cornerstone Macro did a detailed analysis on the impact to inflation of tariffs. It’s believed that the latest tariff hikes will begin to pressure the U.S. Consumer Price Index (CPI) next month; and combined with last year’s tariffs, they estimate peak impact on the CPI in year/year terms will be about 0.25%, likely felt in late-summer (all else equal). The threatened 25% tariffs on the remaining $325 billion of Chinese goods—if implemented all at once—would likely be game-changing for inflation and outlook for consumers.

That $325 billion basket includes $120 billion of consumer goods vs. only $50 billion in the prior rounds; and would likely boost CPI inflation by an additional 0.8%. All income levels are impacted by tariffs on Chinese goods; but of course low income households, which have less of a savings buffer, are most vulnerable.

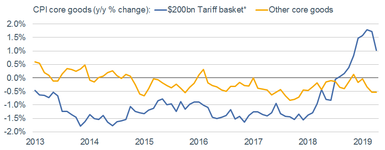

As you can see in the chart below, the 10% tariff on the $200 billion basket of Chinese goods, which went into effect last September, was clearly passed through to consumers. The inflation rate of affected goods swung from -1.5% year/year in 2017 to more than 1.7% year/year in early 2019—contributing about 0.15 percentage points to headline CPI. If anything though, this underestimates the full impact as it does not capture tariffs on intermediate and capital goods, since their effects are more difficult to trace.

Tariff-Targeted Goods Inflation

Source: Charles Schwab, Cornerstone Macro, as of April 30, 2019. *Includes foods, transportation, appliances, electronics, household equipment & furnishings, apparel & accessories, recreational goods, misc.

Cornerstone expects that the just-implemented additional 15% in tariffs on the $200 billion basket will likely cause another step-up in the inflation rate. Assuming a similar pass-through rate to last year’s, inflation on that tariff basket could accelerate by an additional 4.5 percentage points, contributing 0.2 percentage points to the headline CPI.

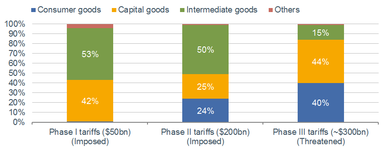

Worse would be if the threatened 25% tariffs on the remaining $325 billion of Chinese goods (Phase III) are implemented. The value of goods at stake is 50% larger and encompasses far more consumer goods, as you can see in the chart below. Cornerstone estimates that the inflation hit from the Phase III tariff basket would be about 2.5 times as large as for Phase II, for an additional impact of 0.8% on headline CPI; a true potential game-changer.

Compositions of U.S Imports from China

Source: Charles Schwab, Cornerstone Macro. Compositions subject to section 301 tariffs.

To date, markets are not showing elevated concern about higher inflation—quite the contrary. But if that complacency persists in the face of higher inflation throughout the summer, investors as well as the Federal Reserve could be caught off guard.

Wipeout?

A mid-May report from the Tax Policy Center (TPC) (https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/taxvox/many-households-trumps-tariffs-could-wipe-out-benefits-tcja) showed that “tariffs could ultimately increase the price of consumer goods by as much or more than the TCJA (Tax Cut and Jobs Act) cut taxes.” The report cites Oxford Economics’ projection that “the total tariff-related reduction in U.S. economic output in 2020 would range between $62 billion and about $100 billion, or between 0.3% and 0.5% of projected GDP. At the high end, it would wipe out nearly all the $115 billion in growth TPC projected the TCJA would create.”

Here are some thoughts from my colleague Collin Martin, who analyzes the corporate debt market: The hit to corporations could impact their ability to finance their debts. Risks have already been brewing, with the amount of debt outstanding having surged, while expected corporate profit growth is extremely weak this year. For now, corporate liquid assets remain high, and the ratio of total liabilities-to-assets remains low (albeit inching higher). However, according to Ned Davis Research, while the liabilities-to-assets ratio for the nonfinancial corporate sector is stable at around 43%, it is significantly higher for the manufacturing sector at more than 58% (and more than 70% for the transportation sector).

Impact on China

None of the above is to suggest China is coming through this unscathed. The aforementioned NBER report showed that imports of tariffed goods dropped sharply as U.S. demand shifted away from China and towards domestically-produced goods and imports from other countries.

On that note, BCA Research recently highlighted an interesting thought experiment:

- One might think that the decision to divert spending from Chinese goods to, say, Korean goods would be irrelevant for the United States’ welfare (economic well-being).

- But suppose that a 10% tariff raises the price of an imported good from $100 to $110.

- If the consumer buys this good from China, the consumer will lose $10 while the U.S. government will gain $10, implying no loss in welfare.

- However, suppose the consumer buys the same good, tariff-free, from Korea for $105.

- Then the consumer loses $5 while the government gets no additional revenue, implying a net loss in national welfare of $5.

- Let’s say the consumer buys an identical domestically-produced good for $107 in order to avoid the tariff.

- If the economy was weak and unemployment was high, the additional demand would boost GDP by $107 (the consumer would be worse off by $7, but wages and profits would rise by $107, leaving a net gain of $100 for the economy).

- However, the U.S. unemployment rate is at a 50-year low; which means that if tariffs shift demand towards locally-sourced goods, it will require that workers and capital be diverted from other uses.

- When this occurs, there is no change in overall GDP.

From BCA: “Most simple models assume that labor and capital are completely fungible and that the economy is always at full employment. In practice, it is doubtful that workers could easily move to companies that benefit from tariff protection from those that would suffer from retaliatory measures. Workers have specialized skills. A piece of machinery that is useful in one sector of the economy may be completely useless in other sectors. Industries are often geographically concentrated in particular areas. As such, a trade war would degrade the value of the existing stock of human and physical capital. This would result in lower potential GDP. It would also lead to temporarily higher unemployment due to worker dislocation.”

The net

As we’ve been opining for some time, although the impact to-date of the trade war has not been substantial in terms of either economic growth or inflation, if it continues to heat up, the impact will be increasingly felt. The indirect effect has already kicked in; with hits to “soft economic” data like business confidence and capital spending intentions. The reason we continue to believe trade will be an important determinant of the length of runway between now and the next recession is because of this confidence transmission mechanism.

The fiscal stimulus of last year helped boost animal spirits through the business confidence channels; along with hopes for a capex-led next leg to the economic expansion. Absent a comprehensive trade deal, it’s hard to imagine a scenario where those animal spirits are reignited.

Copyright © Charles Schwab & Co