by Richard Brink, AllianceBernstein

These are tricky days for the global economy. As growth downshifts and corporate earnings weaken, some investors are dusting off playbooks for late-cycle investing. That makes sense, but there are a few twists to today’s market conditions that may require new responses.

For more than a decade, the global economy has trudged forward in a steady recovery from a near-apocalyptic crisis. Macroeconomic growth patterns are typically seen as a cycle, in which periods of rapid expansion are followed by periods of stagnation that culminate in recession. Today’s environment feels a lot like a late-cycle economy: growth and employment are above trend, while inflation is near its target and financial conditions—interest rates and monetary policy—have tightened from highly accommodative positions in recent years. In the past, conditions like these often ended in recession or, at least, a more challenging investment environment.

Why Is This Cycle Different?

But a closer look reveals some anomalies. Today’s market has been shaped by extreme and unusual policies over a decade. Fiscal stimulus, debt levels, deficits and demographics are adding some uncommon ingredients into the late-cycle stew. Taken together, these could extend the late-stage features of the current cycle for much longer than usual, which means lower returns might be the norm for longer than expected.

Stage 1: The Supercycle Fueled Fundamental Returns

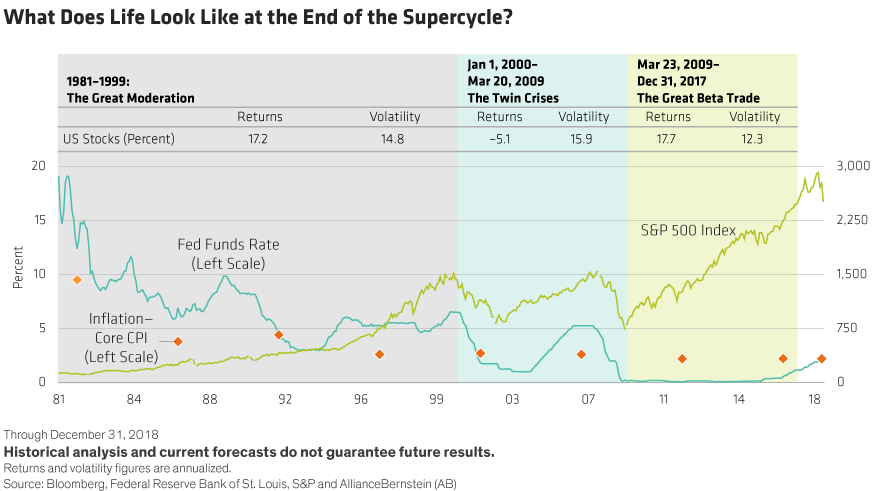

How did we get here? To answer that question, you need to rewind to the beginning of the supercycle in 1981, when the fed funds rate peaked at about 19%. Several things began to unfold that would dramatically change market dynamics for a generation (Display).

First, interest rates and inflation would decline from their peaks for the next 20 years. Second, the baby boomer generation, children of the post–World War II population explosion, entered their prime earning years, which buoyed economic growth and funneled massive amounts of savings into the markets via their retirement plans. Third, a wave of globalization and technological progress began that increased productivity and profitability on an unimaginable scale. This powerful fundamental cocktail drove real wage gains, corporate sales, earnings and, ultimately, the stock market, creating a bull run that lasted nearly two decades.

Stage 2: From the Global Financial Crisis to Leveraged Returns

By the late 1990s, these fundamental drivers started to run out of steam. Inflation had fallen to the 2% target, yields had declined by as much as 15 percentage points and the oldest baby boomers began to exit their peak earning years. Meanwhile, China had taken root as the world’s factory floor, and massive technological advances led to record high stock valuations. Then, the technology bubble burst in 2001 and the seeds of the US housing crisis were planted, leading to the global financial crisis (GFC) in 2008. By early 2009, central banks were pumping oceans of monetary stimulus into markets to avert a catastrophe.

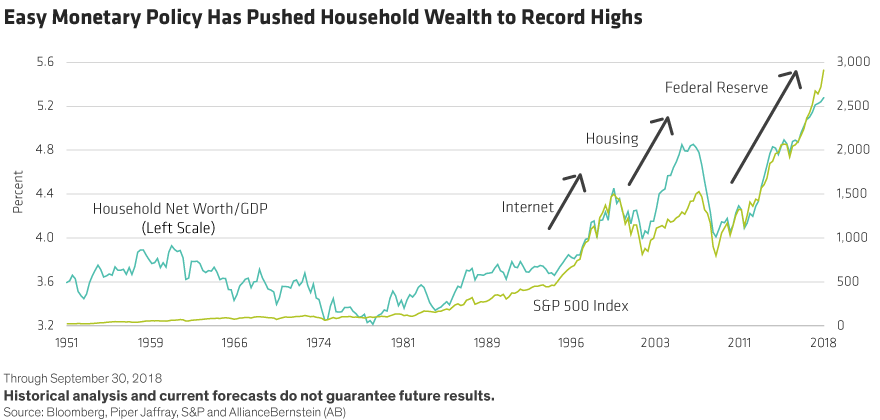

This was the birth of the Great Beta Trade, when central bank policies powered sustained returns with little volatility. Investors could ride the market beta wave effortlessly; since many investment funds with diverse strategies benefited, investors didn’t really need to be aware of what was driving performance. And with so much money sloshing around the markets, downturns were mild and usually corrected themselves quickly.

During the Great Beta Trade, historically low interest rates were like a magic fuel. Household wealth surged (Display) as low rates propped up stock valuations by boosting the present value of future cash flows and incentivizing investors toward equities, since government bonds or savings offered pitiful yields. Low rates also helped companies borrow more to support profitability gains and share buybacks. And in the broader economy, consumers could easily finance purchases of houses, cars and everything in between. This all found its way back into the equity markets, where investors benefited from a virtuous cycle that powered gains, year after year. In contrast to the previous periods, these returns weren’t driven by economic or corporate sales growth, but by cheap, easy borrowing.

And there’s the rub. Leveraged returns are not sustainable. Investors might cheer at net margin improvements and rising valuations. But it’s really just a prolonged sugar rush, without any sustainable nourishment in the form of real revenue gains or economic growth. For example, the benefits of the Trump bump, driven by tax cuts, have already begun to fade.

What’s Next? The Late-Cycle Twist

As all of this comes to an end, return forecasts for the next decade are markedly lower than in the past across asset classes. And four trends add further uncertainty to the late-cycle conundrum:

-

- Fiscal deficit keeps widening—The US deficit typically narrows when unemployment falls. But in recent years, the deficit has kept widening even as unemployment declined. This widening reflects an unprecedented public spending spree that could have unintended consequences for the stability of the world’s largest economy down the road.

-

- Debt burden has ballooned—Low interest rates around the world since the GFC have incentivized borrowing. Global debt has surged by nearly 50% over the past decade and reached approximately US$178 trillion by mid-2018, tripling over the past 20 years. China, the US and many other nations have added to their debt burdens over the past decade. Massive debts and stretched balance sheets could be dangerous if financing conditions tighten.

-

- Baby boomers reach retirement age—As the baby boomers near retirement, the forecast for market returns has weakened and big corrections are more likely. This will create acute challenges as funds are drawn down.

-

- Geopolitical tensions mount—From trade wars to Brexit, new risks threaten to instigate volatility and are adding to the risk of market drawdowns.

Controlling the Path of Returns Is Key

There’s no precedent in modern financial history to help us navigate these conditions. But by identifying the core challenges, we can develop effective solutions.

In an era of low returns, elevated volatility and heightened risk for retirees, we believe that controlling the path of returns is the key to investing success. It’s not only about how much your portfolio returns, but how it’s generating those returns and how it holds up during market downturns. That means investors must pay closer attention to how their portfolios are constructed, how their funds’ exposures will behave as the markets digest these challenges and how skilled their managers are to invest through the uncertainty of what may become the late, late cycle.

The views expressed herein do not constitute research, investment advice or trade recommendations, do not necessarily represent the views of all AB portfolio-management teams, and are subject to revision over time.

Richard Brink is Market Strategist—Client Group at AB

Walt Czaicki is Senior Portfolio Manager—Equities at AB

This post originally appeared at the AllianceBernstein blog

Copyright © AllianceBernstein