by Graham Hook, Head of U.K. Government Relations and Public Policy, Invesco Canada

The latest installment of the Brexit saga went into overtime again on the evening of March 27, as the House of Commons engaged in a first round of “indicative votes” on alternatives to U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May’s withdrawal deal. While the resolution remains uncertain, the contours of a way forward are finally starting to take shape based on voting preferences among the many alternatives put to an indicative vote.

We run through the key elements of the results; their probable implications for the shape of Brexit, the economy and the markets; and what to look out for next.

What happened in the House of Commons?

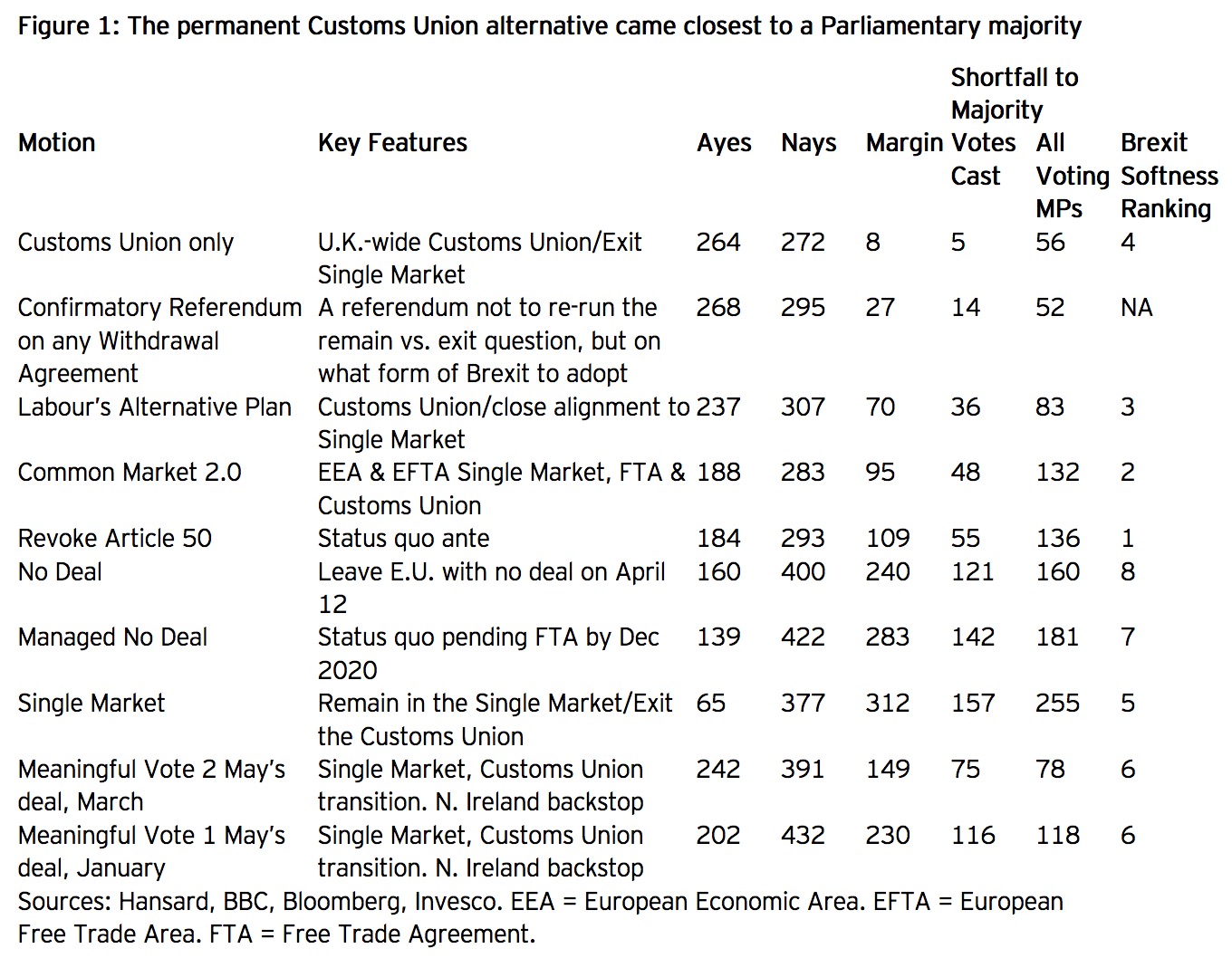

In Figure 1 below, we list the indicative votes on the eight motions considered in the House of Commons March 27. They are shown in order of their shortfall from a simple majority threshold as a direct way to assess both what form of Brexit Parliament would collectively like to see, and what might eventually be put to the European Union (E.U.) if there were to be a new negotiation.

The table includes key features of each of the motions, which are expected to see a next round of indicative votes on April 1, and perhaps even further rounds if a clear majority cannot be established. It is possible that unvoted alternatives or new ones may be tabled for debate and votes during the next or further rounds of indicative votes.

We scale the shortfall against two benchmarks: first, relative to a majority of the votes cast on March 27 (excluding abstentions and absentees); and second, relative to the 320 votes needed for simple majority of the Members of Parliament (MPs) in the Commons.1 We will bear these general thresholds in mind in case the government (or opposition) adopts a firmer hand in trying to “whip” party MPs in any specific direction in the future. It’s worth noting that the Cabinet was instructed to abstain, while other Government ministers and Conservative backbenchers were given a free vote. We therefore interpret these results as reflecting current, unbiased parliamentary preferences.

We have also included the results of the two previous Meaningful Votes (MV1 and MV2) on May’s deal in March and January, which had a significantly greater distance to a majority compared to the parliamentary alternatives, because May’s deal may yet come back to life later this week.

Finally, we have imputed a qualitative “Softness Ranking” to all but one of the parliamentary motions: 1 represents the status quo – full membership of the E.U. Single Market and Customs Union, and 8 represents a no-deal, no-transition Brexit. In general, we believe that the softer the form of Brexit that eventually emerges, the stronger would be the fair value of sterling, the higher the level of Gilt yields, and the lower the equity risk premium on U.K. equities, especially domestic-facing firms.

What did we learn from the votes?

This rendering of the voting preferences provides several useful pointers, in our view:

- Although Parliament has not delivered a majority in favour of any alternative, it came quite close to a majority on various relatively soft forms of Brexit or a reconsideration of the issue:

- The permanent Customs Union alternative was only five votes away from a majority.

- A second referendum on any withdrawal agreement was short by only 14 votes.

- Labour’s alternative – a hybrid of full Customs Union membership with the Single Market (via alignment rather than membership) was short of a majority by 36 votes – a substantial but not overwhelming distance, especially compared to May’s deal or harder versions of Brexit.

- That said, Parliament is very far from revoking Article 50. And it is quite far from the so-called Common Market 2.0 – Single Market plus Customs Union membership.

- Parliament is very strongly opposed to a no-deal Brexit (defined as leaving the E.U. with no transition to trade in goods and services on World Trade Organization terms).

- It is also strongly opposed to other forms of a relatively hard Brexit – such as a managed transition to a Free Trade Agreement

The main inferences we draw from these observations and our ranking are that:

- It seems that Parliament would prefer to deliver some form of Brexit in deference to the original referendum result and is not inclined to rerun a similar “remain vs. exit” referendum, at least not yet.

- The form of Brexit should entail Customs Union membership but an exit from the Single Market, cushioned by a transition. Thus, Parliament at present seems inclined to a softer version of Brexit, though not the softest forms that could be characterized as a Brexit in name only.

- A second confirmatory referendum is in reach as a way of ratifying an actual decision. However, the complexities of formulating the referendum question and proceeding from a rejection of the proposed Withdrawal Agreement would be intensely problematic, just as with a new Brexit referendum. For example, would the alternative to the proposed Withdrawal Agreement be to remain, or to aim to respect the original referendum result – the latter could set the Brexit process back to square one.

Three further important political points stand out from the evening’s proceedings:

- First, the earliest Brexit date has now definitively been delayed from March 29 to April 12 thanks to a strong majority vote of 441 to 105 in favour of aligning U.K. law with international law.

- Second, May’s deal faces high hurdles, though the Prime Minister and some senior politicians remain committed to it. The House of Commons’ speaker promulgated a new procedural ruling that makes it more difficult for the government to hold a third meaningful vote on May’s deal without substantive changes to the Withdrawal Agreement package. In response, the government has announced plans to table only the Withdrawal Agreement – without the Political Declaration – for a vote. The Speaker has accepted this change of tack as meeting his substantive change litmus test for allowing MV3. Indications from the E.U. are that the Withdrawal Agreement would suffice to get Brexit over the line. If passed, the Brexit date would shift to May 22 to allow time for the U.K. Parliament to pass the required legislation, by agreement between the government and the E.U.

We would expect considerable opposition, though this change could improve the chances of May’s deal somewhat. The most controversial element – namely the Irish “Backstop” – is in the Withdrawal Agreement (a legally binding treaty) rather than the Political Declaration (a non-binding statement of intent about future U.K.-E.U. relations).1 The Conservatives’ junior coalition partner, the Democratic Unionist Party, indicated that it remains opposed to May’s deal. The hard Brexiters are likely to continue to oppose the deal because of the risk of remaining permanently in a Customs Union. And Labour, despite not having specific issues with the Withdrawal Agreement, has indicated that it opposes the Withdrawal Agreement without the Political Declaration as a “Blind Brexit,” presumably sensing another political opportunity to undermine the government.

- Third, May has indicated she will step down as Prime Minister ahead of the next phase of the Brexit negotiations (assuming her deal passes). She did not set a date for her departure, but if her deal were to be passed this week and the Article 50 period extended until May 22, the formal Conservative leadership contest would be triggered very shortly after. May would remain as Prime Minister during the leadership contest. The precise timetable would be set by the Conservative Party.

Political possibilities: Brexit before the end of May?

We note that May’s conditional commitment to step down leaves open the possibility that she could yet cling to power if an alternative option is agreed upon between Parliament and the government.2

If May digs in her heels, she may complicate future negotiations with the E.U. as well as her authority to manage the U.K. government. Alternatively, if she refuses to accept any of the alternatives offered up by the indicative votes, other possibilities will come into market focus, including a leadership struggle within the Tory Party or Parliamentary motions of no-confidence in the government to secure an early election. What’s more, permanent Customs Union membership contradicts the Tory Party manifesto for the 2017 general election, which could present May with yet another difficult choice – break a campaign pledge and further exacerbate party divisions or risk an early election to resolve the issues. All this implies that the Prime Minister or the government could yet fall, in which scenario E.U. acquiescence would be required for an extension to accommodate a leadership struggle within the Conservative Party or a new election.

Such scenarios would extend uncertainty both about Brexit itself and about the general direction of U.K. policy, and would require a longer extension of the process to be agreed upon by the E.U.3 The official E.U. position is that the U.K. must decide whether to participate in E.U. Parliament elections for which the deadline is April 12 – hence the new Brexit deadline. Brexiter politicians adamantly oppose participation given the result of the Referendum, but Remainers are more likely to participate, naturally. A workaround could be found based on precedents – some E.U. members temporarily seconded national MPs to the E.U. Parliament upon joining – but like everything else connected to Brexit, this requires elusive compromise.

However, if the May government and Parliament are able to agree on a way forward by April 12, we believe the E.U. would stand ready to offer a long enough extension to encompass a general election, a referendum or possibly even a renegotiation of the Brexit process – despite the doubts that some member-states have raised with the E.U., as indicated by European Council President Donald Tusk. While the E.U. and member states want to resolve the Brexit uncertainty as fast as possible, they would also want to avoid a no-deal Brexit. A no-deal scenario would undermine the E.U. economy overall, and would be expected to severely damage the economy of not just the U.K., but also Ireland and some the smaller member states with which the U.K. has close trading links. Such factors could affect the May E.U. Parliamentary elections, which are already expected to see a rise in the representation of anti-E.U. parties.

Economic and financial market implications

Stepping back, we believe that the general trend in the Brexit process is toward a softer rather than harder form of Brexit – though major uncertainties persist that are likely to continue to weigh on growth in the U.K. and eurozone.

First, Parliament’s indicative votes suggest a willingness to retain Customs Union membership to protect the U.K.’s privileged access to the large E.U. markets for merchandise trade (in which the U.K. shines only in a few high-end sectors but is otherwise lackluster and with manufacturing less than 10% of gross domestic product). However, Parliament seems less eager to hold on to the Single Market (useful for services trade, in which the U.K. excels, and with services at 80% of GDP). Parliament may prefer staying in the Customs Union to Single Market membership, despite the greater economic costs, because it collectively interprets the referendum result as reflecting popular dissatisfaction with globalization including free movement of people within the E.U., technological change and “financialization,” which are widely seen to have widened income and wealth inequality across the country, exacerbated by a perceived loss of legislative and judicial authority under the rules of the Single Market.

This interpretation implies that achieving political stability by addressing inequality is becoming more important than economic growth, efficiency and productivity growth per se, as well as the sheer scale of market access, in public policy choices. If so, the financial market implications would be a weaker fair value for sterling, lower Gilt yields and higher equity risk premia than prior to the referendum. More comfortingly, however, this interpretation also implies that the U.K. is not prepared to turn away from its largest trading partner, or run the risk of a plunge in economic activity in order to seek trade deals elsewhere – and reaffirms that the political shift can be accommodated via transition rather than a revolutionary economic shock.

Second, we caution that although the indicative votes have shed some light on Parliament’s preferences, there is still plenty of room for yet more disagreement, disappointment and delay – not least because the government has indicated that it will resist the will of Parliament, which could open the door to a new political process such as a referendum or election.

Such a reconsideration might yield quite a different approach to Brexit than May’s deal or could conceivably obviate Brexit, but the extended uncertainty would probably weigh further on business and household confidence, causing further delays in major investment and consumption decisions, weakening growth and keeping sterling volatile and weak. Gilt yields could remain low or fall even further, and via the additional drag on eurozone growth, could contribute to already rising concerns about falling global growth and inflation.

Wider ramifications: Brexit is not just a U.K. problem

We continue to believe that an amicable resolution to the Brexit quagmire would be a favourable political and economic signal not just for the U.K. or the E.U., but for the global economy – and that a no-deal Brexit could have negative implications for other geo-economic and geopolitical tensions.

Within the U.K., the rancor within the political system and popular polarization may be exacerbated by a no-deal scenario, a revocation of Article 50, a new election or referendum – at least until and unless there is a clear and unequivocal majority in favour of a specific form of Brexit or a choice to remain. All of the above would therefore very likely continue to drag on investment and household confidence.

For the E.U., concerns about nationalism and populism continue to run high both within member state political systems as well as the E.U. political system – where anti-status quo parties could make a strong showing in this May’s European Parliamentary elections. If populist parties get their act together and actually make a sustained and strong effort to redirect the E.U. legislative process, they could have a meaningful impact on E.U. policy. Being able to re-engage with the U.K. as a continuing member, if at all possible, could be a good route – perhaps the best-case scenario – for political stabilization, renewed economic reform and stronger growth for the E.U. as a whole, in our view.

As a base case, managing Brexit amicably towards a softer outcome with a transition rather than a shock would send an encouraging signal – that reasonable governments, like reasonable people, may disagree about many issues, yet be able to resolve differences and engage constructively in other areas. Indeed, we are encouraged that this is the direction of travel in U.K. politics, even though the risks remain very high and the time frames too short to fully rule out a major shock.

With contributions from Graham Hook, Head of U.K. Government Relations and Public Policy, Invesco

This post was originally published at Invesco Canada Blog

Copyright © Invesco Canada Blog