by Keith Brakebill, Russell Investments

December offered credit investors a taste of what a real cyclical downturn might look like in a post-GFC (global financial crisis) world. Unsurprisingly, most did not enjoy the flavor.

In concert with other risk assets, corporate credit saw considerable volatility and losses late in the year. What was troubling to many in the market, however, was more than the magnitude of the loss. To wit, the U.S. high-yield market was down 4.5% during the fourth quarter1—bad, but not catastrophic. The more significant concern among many came from the utter dearth of liquidity and trading during a period of such volatile price action—and the resulting impact on performance irrespective of fundamental dynamics. Essentially, only the ETFs (exchange-traded funds) were trading, while most other individuals were either away on holiday or staring at their screens, watching bonds go whichever direction ETF cash flows went.

Thankfully, the market snapped back quickly to start 2019. However, we believe there are lasting lessons to be learned in how to prepare for a larger and more lasting sell-off that will inevitably hit at some point.

Is the end of the credit cycle near?

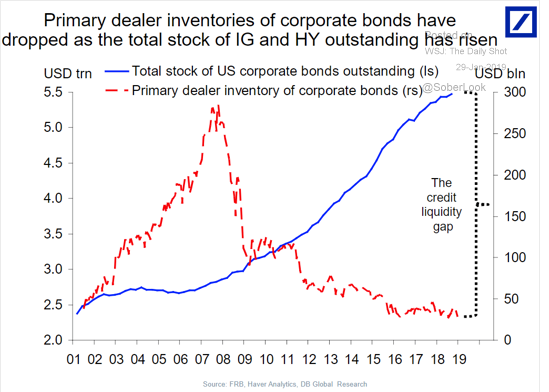

We’re not the first firm to sound an alarm bell over liquidity in the fixed-income credit markets. Indeed, that bell has been ringing non-stop since the since the collapse of Lehman Brothers. The risk has only grown in recent years as regulations pushed market makers out of the business, in spite of record growth in the size of the corporate bond market.

Source: Deutsche Bank Research

All these alarm bells have fallen on deaf ears for the most part. As a consequence, few investors have altered the way they invest in the corporate market. Some simply don’t think they need to. Others are making things even worse, on both themselves and the market, by fueling the growth in corporate bond ETFs. This has exacerbated the market illiquidity issue in two ways:

- First, because ETFs dominate intraday trading volume, yet have a fairly concentrated set of holdings, they cause what little dealer balance-sheet liquidity remains to be concentrated as well. This has left the rest of the market even less liquid than the decline in the dealer balance sheet would suggest.

- Second, encouraging intraday trading of an asset class—where most securities do not even trade daily— has led to more severe pricing jumps in securities across the market.

Now, all of the above fear mongering may seem like just that. After all, liquidity is something that investors only need when they want to sell, and in the post-GFC world we really haven’t seen a prolonged period of selling. Sure, there have been waves, but the tide has never fully gone out as in prior full-cycle rollovers. But, this credit cycle is getting long in the tooth. Leverage is high and lending standards are low. There’s little room for coming up short of expectations on growth.

Hence, we believe it’s time for investors to consider how they should think about managing credit exposure in anticipation of the full-cycle rollover. Given the likely lack of liquidity, we believe that waiting until the cycle starts collapsing will be too late. Rather, we see two main options to weigh in order to get ahead of the next liquidity crunch.

Option #1: Fallen angels

First of all, surviving a liquidity crisis won’t be as simple as merely picking good companies and riding out the storm. In a market with no liquidity, price performance is erratic and indiscriminate of fundamentals. Even if you have the ability and willingness to live with the stomach-churning volatility, selecting companies that seem to have good fundamentals today will likely not be enough to come out the other side unscathed. Why? Because the definition of good changes in a liquidity crunch. Instead of worrying about which companies can generate enough earnings to cover the cost of borrowing over the long term, the only thing that really matters in such a situation is which corporations can come up with the cash to meet their immediate needs for payroll, bond maturities, etc.

In short, you need to either own the debt of companies that can live without the market or the debt of companies that the market heavily relies on. This is why, at Russell Investments, we tend to bias our high-yield portfolios toward fallen angels—bonds of companies downgraded from an investment-grade rating. These companies’ bonds tend to have long maturities (i.e., less immediate cash needed as a result) and more numerous, larger stakeholders with incentives (equity holdings, future investment banking fees, etc.) to extend the company a cash lifeline in times of crisis. While fallen angels are subject to the same volatility during market turmoil, they also tend to have the key advantages necessary to survive a liquidity crisis and thrive on the other end.

Option #2: Cash, in combination with derivatives

There is one truism in a real liquidity crunch: Cash is king. It’s true at the company level, as suggested above, but also at the portfolio level. Why? It does an investor no good to identify undervalued, home-run opportunities in a crisis when their portfolio is already tied up in bonds that have become untradeable. Rather, you are stuck with whatever horse you rode into the crisis… unless you have cash.

Of course, the trouble with cash is that, by itself, it doesn’t earn very much and unless you get the timing just right, it generates significantly lower returns than corporate bonds. However, derivatives can allow for substantial flexibility these days. At Russell Investments, one of our strategies is to hold cash, in combination with derivatives, to generate market-like returns in the interim—while waiting for the opportunity to pounce on extreme opportunities when they present themselves.

This does mean that in the short-term, we explicitly give up some security selection possibilities. However, in our view, this is just a more honest reflection of the fact that when the market is calm, security selection opportunities are naturally small. It’s better, in our opinion, to not chase too many modest opportunities today, in order to ensure that we have the ability to take advantage of home-run opportunities when they arrive.

The bottom line

Yes, the market and press have been crying wolf over bond liquidity for years, and yes, high-yield corporate bonds have delivered solid returns over most of that period. But that doesn’t mean we should just ignore these warnings. We firmly believe the risks are real and will eventually be laid bare for all to see once the tide goes out for good on this credit cycle. At Russell Investments, we’ve been utilizing a number of strategies that we believe will better insulate investors from liquidity risk, such as favoring fallen angels and holding cash with derivatives to maintain market exposure. In our view, strategies like these may allow portfolios to transform the next liquidity crunch from an exercise in survival into a smorgasbord of opportunity.

1 Source: Bloomberg data as of 12/31/2018. Market performance as measured by the Bloomberg Barclays U.S. Corporate High Yield Bond Index

Copyright © Russell Investments