by Charles Roth, Thornburg Investment Management

While investors should be cognizant of the complexities and risks around Brexit, they should be just as aware of the opportunities in select U.K.-based businesses.

How should an investor position for Brexit? As the end-March deadline approaches for the U.K. to leave the European Union with or without a “withdrawal agreement,” markets have been increasingly on edge. There doesn’t seem to be any way for the U.K. to disentangle a Gordian knot whose ends are tied in Brussels and Ireland, and exit the common market while retaining favorable access to it.

Failing a mutually amicable divorce, the possibility of the U.K., however reluctantly, cutting clean its ties to the E.U. rises sharply. Markets fear the adverse economic impact that a “hard Brexit” will have on E.U. and especially U.K. asset prices. U.K.-listed stocks have noticeably lagged regional and developed world equity benchmark returns since the country’s June 2016 referendum on E.U. membership, with the MSCI U.K. Index returning 2.7% annually in U.S. dollar terms since then, compared to 5.7% for the MSCI Europe ex-U.K. Index and the MSCI World Index’s 9.7% yearly gain in the same period.

Just two weeks after the U.K. Parliament’s historic drubbing of Prime Minister Theresa May’s withdrawal deal with the E.U., the House of Commons on January 29 voted for two amendments: one symbolically declaring their opposition to a hard Brexit, and the other calling on May to renegotiate an exit that doesn’t include roping the U.K. into an E.U. customs union via Northern Ireland, where all sides hope to prevent the return of a hard border on the island. But both Brussels and Dublin have insisted that the “Irish Backstop,” as it’s known, isn’t open to renegotiation.

Despite convoluted flow charts illustrating all the possible twists and turns ahead of an ultimate outcome, the only options remaining include a hard Brexit, a “soft” negotiated Brexit, or no Brexit—if enough U.K. citizens have second thoughts, perhaps expressed in a second referendum, and ask Brussels to never mind—they’ve decided to stay in the E.U. after all. Given how little time remains, though, odds are rising that the U.K. will ask for and receive an extension beyond the March 29 deadline. But the E.U. has warned that “serial extensions” aren’t in the cards. That’s why oddsmakers see chances of a hard Brexit rising. Capital Economics raised that likelihood from 25% to 30%, vs. the probability of May’s negotiated deal rising from 5% to 15%. It puts the odds of delay at 55%, according to the Financial Times.

Risky Business

Notwithstanding the drag on U.K. equities of Brexit’s overhang, some U.K.-based businesses are more exposed to a hard Brexit than others. Certainly even the less exposed, domestically focused firms still face the prospect of higher customs and tariffs costs related to, say, inputs imported under World Trade Organization (WTO) rules, to which the U.K. must resort failing a graceful exit from the single bloc. Yet investors should keep in mind that some companies will always fare better than others, given individual business fundamentals, and that when share prices diverge from those fundamentals in broad market swings, investment opportunities arise.

To be sure, investors generally and the U.K.’s storied multinational banking firms in particular have all along hoped for a soft Brexit that lands the U.K., like Norway, in the European Economic Area and allows most of its exports tariff-free access to the E.U. But in exchange for that access, Oslo allows E.U. citizens the freedom to work and reside in Norway, kicks in heavily to the E.U.’s budget and follows slews of Brussels’ rules, over which it has little formal say, though it is exempt from E.U. regulation on home affairs and justice. U.K. Prime Minister Theresa May has vetoed this framework, given its constraints. “Brexit means Brexit,” she has declared time and again.

Some have also suggested a “Canada-style” trade deal with the E.U. But it took roughly seven years to hammer out and became only provisionally effective in late 2017; it’s still pending ratification by national parliaments in several E.U. member states and a half dozen regional parliaments. Crucially for the U.K., it doesn’t include “passporting,” the bilateral sale of financial products within their respective territories. Nearly a third of the U.K.’s total services exports to the E.U. are financial in nature. And as services comprise four-fifths of the U.K.’s economy, and as the ratio of its financial services exports to GDP is also about a third—the highest in the Group of Seven industrialized nations—that’s a problem.

Red Lines and Borders

But perhaps the biggest quandary involves the treatement of the Emerald Isle's land border, which is a key part of the U.K.’s narrower, and binding, departure terms. These are distinct from the non-binding, yet-to-be negotiated trade and economic relations wish list, which are supposed to be worked out over a nearly two-year transition period after a negotiated Brexit happens, with temporary E.U./U.K. regulatory overlap providing legal continuity for businesses in the interim. Yet May’s “red-lines” proscribing the free movement of people, the European Court of Justice’s jurisdiction in the U.K., and the U.K.’s post-Brexit participation in the E.U.’s customs union and single market, mean that many big U.K. businesses are preparing for a hard Brexit, while others are now moving fast in that direction.

How does Ireland factor in? While neither the Norwegian nor Canadian deals involve membership in the E.U.’s customs union or single market, Norway does share a border with Sweden, an E.U. member. It has border stations overseeing customs-related paperwork and security to intercept smugglers trying to game different tariff and pricing regimes on, say, alcohol and tobacco in the two territories. Northern Ireland is part of the U.K., while the Republic of Ireland is an E.U. member and with E.U. backing insists on the backstop to keep an open border on the island. Dublin and Brussels both say no time limit can be attached to the backstop, and that it isn’t up for renegotiation.

May’s Conservative Party enjoys no parliamentary majority and so depends on Tory hardliners and Northern Ireland’s Democratic Unionist Party for support in Parliament, and they reject the backstop, fearing it will create dual customs and regulatory regimes within the U.K. or effectively entrap the U.K. within the E.U. customs union. On the other side of the House of Commons, the vast majority of the Labour Party doesn’t want to see the U.K. part ways with the E.U., though 10 Labour lawmakers voted with May as they support Brexit. Yet neither party wants a “hard border” with physical barriers dividing Ireland again, endangering the 1998 Good Friday Agreement that opened the border and brought peace between the mainly protestant North and Catholic South. Dublin worries that dissident republicans might target border checkpoints and related physical infrastructure.

Some have suggested that perhaps advanced technology and digital scanning to speed customs clearance could do the trick and preclude the need for physical checkpoints. But Leo Varadkar, the Republic of Ireland’s prime minister, rejected the idea in an interview with Bloomberg in Davos: “I have yet to have anyone demonstrate to me a technology that can look into a truck and tell me whether there’s hormones in the beef or not.”

Alternative Arrangements

Perhaps “alternative arrangements,” as vaguely proposed in the approved amendment seeking to replace the backstop, will somehow be accepted in Brussels and Dublin. More likely is the extension of the March 29 deadline. There are no guarantees, though. As Michel Barnier, the E.U.’s chief Brexit negotiator, warned last week, “Preparing for a no-deal scenario is more important now than ever, even though I still hope we can avoid this scenario.” And a hard Brexit, intoned European Commission spokesperson Margaritis Schinas the day before, means a hard border in Ireland. “I think it’s pretty obvious.”

Given the Brexiteers’ red lines and the backstop deadlock, a number of London-based financial firms with business in the E.U. are already establishing an operational presence on the continent to retain access to the bloc. A diminution in their staffing and activities in the City of London is an economic loss. It’s the same story with supply chains and end markets in the manufacturing and pharmaceuticals industries. British-owned airlines are also at risk of having their inter-E.U. country flights cancelled.

Investors certainly need to factor in potential fallout of a hard Brexit for U.K.-domiciled stocks. Hard Brexit implies U.K. and E.U. cross-border tariffs based on WTO regulations, which mean tariffs generally running from 4% to 40% on individual products and billions of dollars in additional costs from new customs declarations and revised customer contracts, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis. This worst-case scenario would create a drag on the U.K.’s GDP growth for several years, according to both the Bank of England and the International Monetary Fund, before recovering from the initial blow.

Political Risks and Business Fundamentals

But if the U.K. devises trade and economic policies akin to those of Singapore or Switzerland, which isn’t a member of the EEA or the E.U. (but like Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway, is a member of the European Free Trade Assoc.), it should do fine in time. After all, Britain has been a maritime trading nation plying the world’s sea lanes for centuries. More than continental Europe, the U.K. also has a deep, vibrant entrepreneurial culture that’s difficult to replicate. Perhaps that’s why the U.K.’s weighting in the MSCI All-Country World Index stood at 5.2% at the end of 2018, almost double Germany’s 2.7% and well ahead of France’s 3.4%.

“Brexit or no Brexit, is this a good business?” asks Thornburg Portfolio Manager Greg Dunn. “Over the years, we’ve seen political risks come and go, but you can get into trouble if you try and invest around them.” For example, after the Brexit referendum passed in June of 2016, U.K. stocks dipped, but the MSCI U.K. Index in dollar terms then rebounded and finished the calendar year largely flat. The index climbed 22% in 2017, and shed 14% last year, a return largely in line with the MSCI EAFE Index.

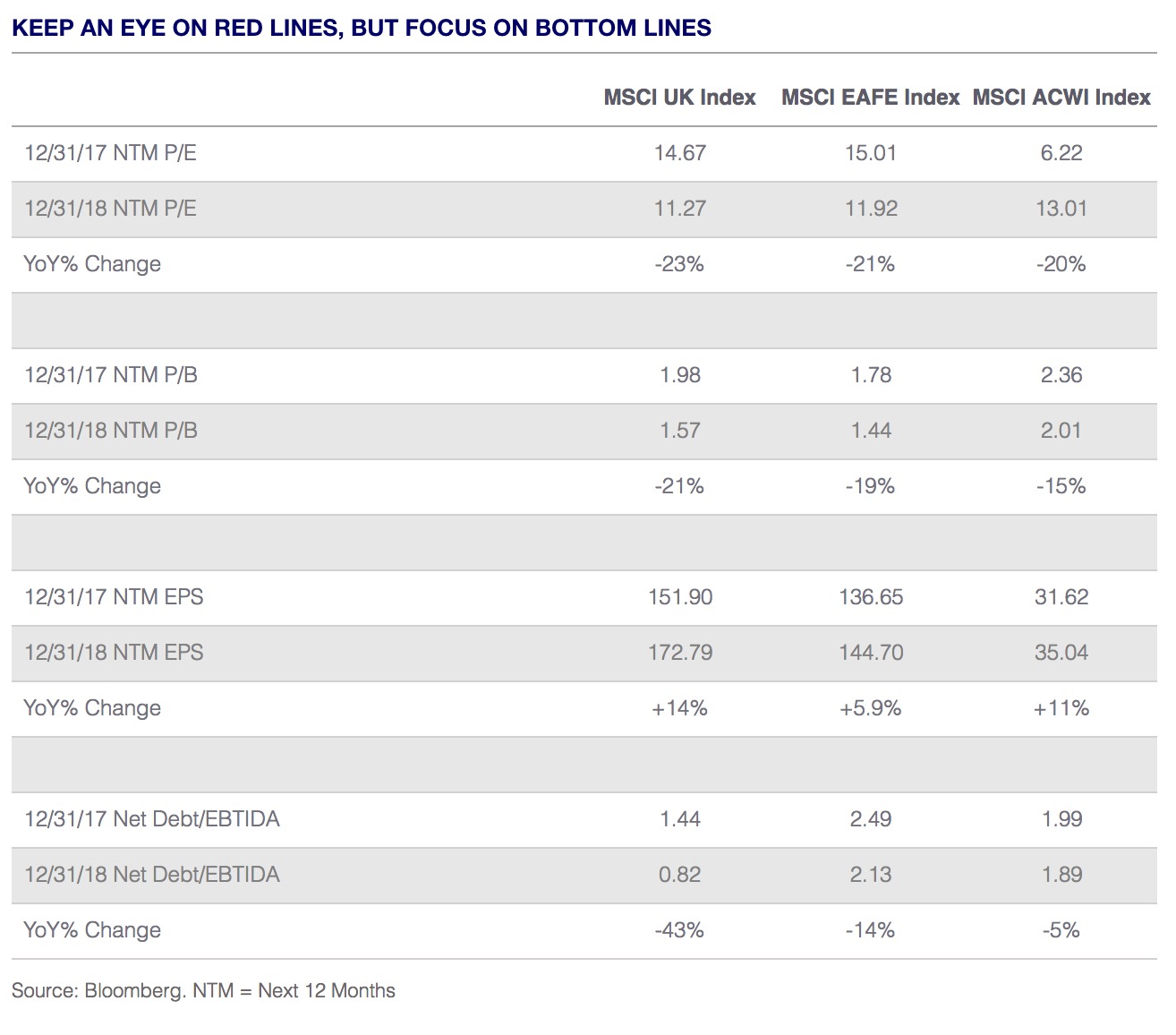

To be sure, U.K. banks are quite exposed to a hard Brexit, but some domestic-focused non-bank financials, including select U.K. fintech firms, offer compelling investment propositions given their long-run growth trajectories, notes Sean Sun, another Thornburg portfolio manager. Dunn and Sun point out many U.K. stocks sport attractive valuations, strong balance sheets, and growing cash flows. Some are domestically focused across several sectors while others are exporters well beyond Europe. And those worried about currency volatility can easily and relatively cheaply hedge their currency exposures.

For investors with a long-term view who base their valuations on projected cash-flows and profits of select U.K. firms two to four years down the road, Brexit-related setbacks can be overcome, and may well offer opportunities in stocks that are caught up in broad market turbulence but only indirectly exposed to cross-border risks. Current valuations on U.K. stocks on a relative basis at the index level are quite appealing, though select individual names may have better or worse prospects. Successful investing is always about distinguishing share price divergence from individual business fundamentals, within a broader macro environment, in all geographies.

Copyright © Thornburg Investment Management