by Jurrien Timmer, Director of Global Macro, @TimmerFidelity, Fidelity Investments

The last emerging-market (EM) rout was rescued by the Fed; a reprise may be wishful thinking this time.

Key takeaways

• Emerging markets are back in focus, with financial turmoil hitting Turkey.

• Unlike 2016, when the U.S. Federal Reserve took pressure off emerging markets by slowing its pace of monetary tightening, this time the Fed may not have that luxury.

• That means that there are likely no quick fixes to EM problems.

• Meanwhile, the U.S. stock market is back near its January highs, but I think enough potential headwinds are out there to keep the now six- month-old trading range intact.

• 2019 could prove a pivotal year for U.S. stocks, as I see earnings growth slowing back to trend by then and the Fed getting further and further into restrictive policy.

Investors are watching EM

With Turkey exploding back into the headlines—the Turkish lira has lost close to 40% of its value year to date through August 151—it’s a good reminder that although the U.S. economy remains strong, the same cannot be said across the emerging markets. And unlike what happened in 2016, this time around we likely can’t count on the U.S. Federal Reserve to open the liquidity spigot and, in turn, dampen U.S.-dollar strength.

While the S&P 500® is back near its all-time high (reaching 2863 on August 7, 2018, versus the 2873 record set in January), the MSCI World ex USA Index is down around 12% since its January 26 peak and the MSCI Emerging Markets Index is down nearly 20%, within which Turkey was off a whopping 55% (all data as of August 15). Moreover, the Euro Stoxx® Banks Index is down some 26%. European banks always seem to have a front row seat to the happenings in emerging markets. In this case it’s the Spanish banking system where the biggest exposures are.

On its own, I don’t think Turkey should pose that much of a systemic risk to the U.S. or global markets. Like Argentina, Turkey is only a small part of the EM index, and it is not a highly indebted country overall (debt/GDP there is a little over 40%, although that ratio is roughly double if one looks just at credit to the non-financial sector versus GDP). But a fair amount of sovereign and corporate debt is in foreign hands, which is always risky. Therefore, the crisis could develop into contagion if Turkey imposes capital controls to stem the bleeding.

This in turn could lead to investors unwinding positions elsewhere (as the old adage goes: if you can’t sell what you want, sell what you can). So far this has not happened, and it is not our base case. But clearly this is an important line in the sand for Turkey and, more generally, EM equities as an asset class. (Keep in mind, though, that the World Bank ranks Turkey as only the 17th largest economy as of 2017, with a GDP less than Apple’s current market cap!)

Turkey is not the only news of course. China is another developing story and could indeed prove to be systemic for global markets. The Chinese economy has been doing OK in the grand scheme, but it has been slowing in recent months, to the point where the government is now easing fiscal and monetary policy. Indeed, China seems to be following its two-year CRIC cycle2 (crisis. response. improvement . complacency) with good accuracy.

The problem with China’s slowdown and concurrent policy easing is that it is happening at a time when the U.S. economy is strong and the Fed is tightening. Because China’s currency is tied to the U.S. dollar, China is essentially importing U.S. monetary policy. That’s fine when the two economies are synched up, but not when they are diverging, as is presently the case. The result of all this is that the Chinese yuan has fallen back near its 2015–2016 lows. So far, China’s currency depreciation is not as systemic as it was in 2016 (evidenced by the stability of its foreign-currency reserves), but it’s something that should be watched.

Trade remains an obvious concern, of course. The risk is that escalating trade tension could lead to “stagflation,” resulting in P/E (price-earnings) compression around the world. With the S&P 500® near all-time highs and, as of August 15, the Shanghai Stock Exchange Composite Index down about 23% since January 26, it’s easy to declare winners and losers, but rising tariffs could cause a one-two punch for all markets in the form of declining profit margins coupled with rising prices. If there is one thing we’ve learned from studying economic history, it’s that stagflation equals a headwind for valuations.

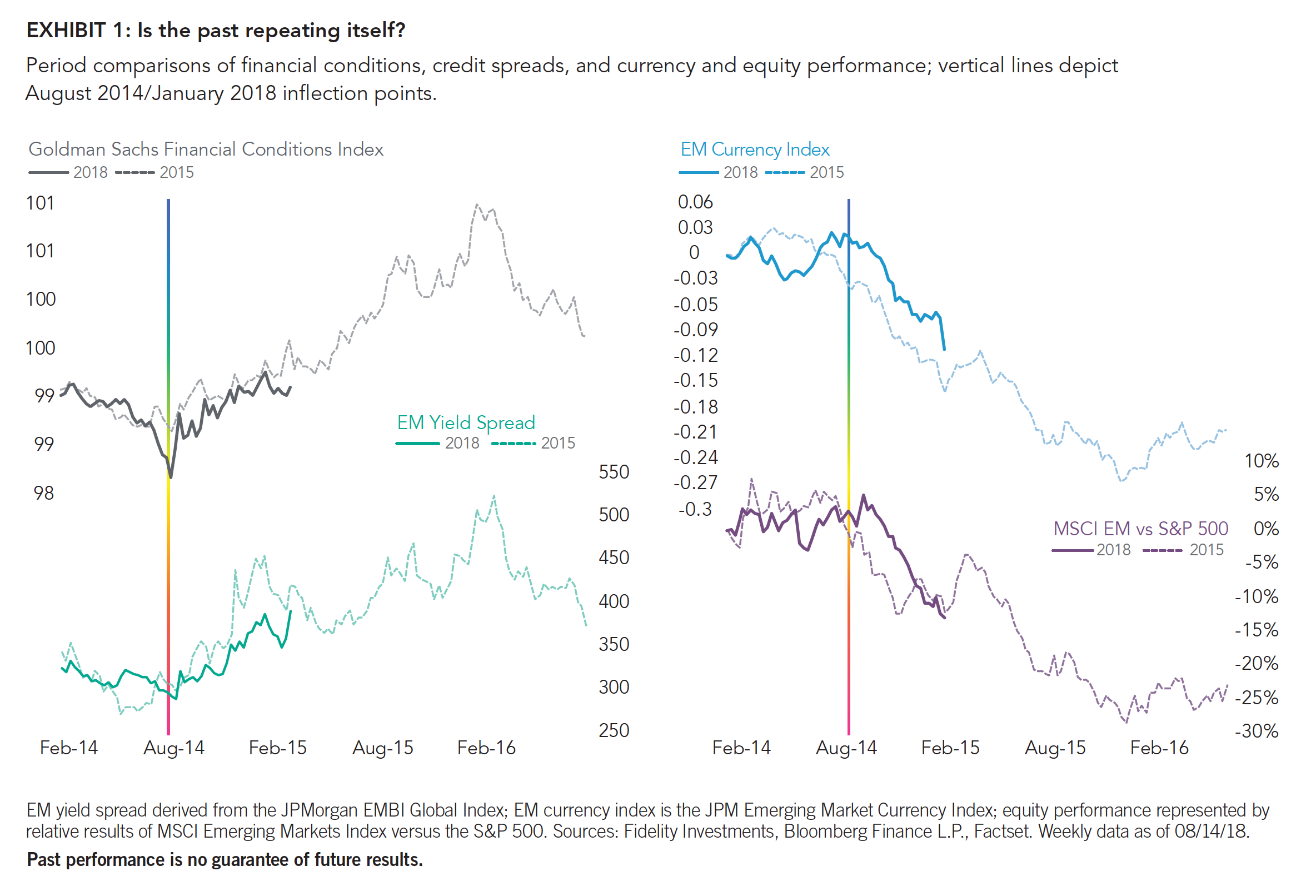

EM equities continue to track the 2014–2016 analog with close precision, despite the fact that the earnings backdrop in emerging markets is better today than it was a few years ago. Exhibit 1 (on page 3) shows the analog across various metrics and links the two periods to the point at which liquidity conditions (as measured by the Goldman Sachs Financial Conditions Index) started to tighten (August 2014 versus January 2018).

The last EM rout ended in early 2016 when the U.S. Federal Reserve was forced to dial back on its hawkish forward guidance. In effect, the Fed “eased” simply by tightening less than the markets had priced in, proving once again that we live in a “flow” and not a “stock” world (i.e., rate of change matters more than absolute level).

But that was two and a half years ago. Back then the Fed had the luxury of operating in a regime of secular stagnation (or at least persistently anemic growth) and inflation was well below target, which allowed the Fed to ease off the throttle in terms of its tightening path.

The Fed had nothing to lose by not tightening as quickly as it had telegraphed; the impact was the same as a rate cut.

The same cannot be said today, however. I don’t think we can count on the Fed lowering its guidance to bail out emerging markets anytime soon, in the process bringing down the U.S. dollar and allowing financial conditions to ease. This time around, the secular-stagnation era seems like a thing of the past, and we are edging ever closer to the late stages of the business cycle. Last week’s 2.4% core CPI print was a good reminder of this. (The core CPI, or Consumer Price Index, is calculated by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and excludes the relatively volatile prices for food and energy.)

Without the Fed coming to the rescue, this EM rout likely will have to be resolved the old-fashioned way: through hard medicine. In emerging markets, that generally means central-bank tightening, currency devaluation, recession, and painful fiscal adjustments. Argentina offers a good example of this, as the central bank there just raised its policy interest rate to 45%.

Clearly the yawning performance gap so far this year between the S&P 500® (hovering near its all-time highs and up about 7% year to date as of August 15) and EM equities (down about 11% year to date) is begging to be looked at from an asset allocation perspective. I think it’s too early still, but at some point this will become an important action item for global investors.

What does all this mean for U.S. markets?

A few days ago it looked like the S&P 500® Index was ready to overtake its January highs, but the crisis in Turkey serves as a good reminder that there are still some big potential headwinds out there. The U.S. dollar is still strengthening versus many currencies, financial conditions remain on their tightening path, and now it is starting to look more and more like earnings growth is putting in a post-tax cut cyclical peak at about 24%.

U.S. corporate earnings have been booming this year, helped in large part by the corporate tax cut. First- quarter earnings3 were up 23% year over year, and second-quarter earnings were up 24%. This surge has been happening while earnings outside the U.S. continue to decelerate from around 20% back down to the single digits.

The boom in U.S. earnings has enabled domestic equity- market valuations to descend back down to earth without any pain so far in terms of stock prices. To wit, the forward P/E ratio for the S&P 500® is down 3 points in 6 months (to 16.5x) while the price index is basically unchanged (after climbing back from a 10% dip early in the year). We have the earnings boom to thank for that.

However, we are seeing signs that the rate of change for U.S. earnings may be starting to peak. Unlike what happened in the first quarter—where earnings estimates gained across the board—the rise in second-quarter estimates seems to be coming at the expense of the third and fourth quarters. Third-quarter estimates are down 230 basis points (bps) from their highest levels a few weeks ago, while estimates for the final quarter of 2018 are down 120 bps.

That’s not to say that the level of earnings is starting to decline, of course; just that they may have reached their peak growth rates for the year. This is not necessarily a risk for stocks, but it does mean that the valuation math likely will start to get incrementally less favorable from here.

My expectation is that the stock market is not yet ready to break out to new highs and that we will remain in this lateral range for a while longer. There are simply still too many crosscurrents, with booming (but peaking) earnings growth on the one hand and tightening liquidity conditions (resulting from the Fed cycle) on the other. The result is a sideways market that could produce a healthy valuation reset.

I still expect that 2019 will be a pivotal year for stocks, as I think by then earnings growth should be back down in the single digits, while the Fed will likely be three or more hikes further into its cycle. If in 2019 the Fed is close to the end of its normalization path, U.S. stocks could be in good shape to resume their epic bull market. But if inflation forces the Fed to go well beyond what is currently expected, the story could be much different.

As I see it, the biggest threat to the U.S. markets (outside of a rapidly escalating trade war or some geopolitical crisis) is inflation. If inflation heads north and forces the Fed to tighten substantially more than the market is discounting—at the same time that earnings growth is decelerating—then this could cause a significant tightening of financial conditions, an inversion in the yield curve, and further compression in P/E multiples. Without an earnings boom to compensate for such events, a serious decline in stock prices could result. Again, that does not represent my base case, but with the U.S. economy heading toward late cycle, to me it’s the scenario that poses the greatest risk to this nineyear- old bull market.

For now, patience is a virtue.

Author

Jurrien Timmer | Director of Global Macro | Fidelity Global Asset Allocation Division

Jurrien Timmer is the director of Global Macro for the Global Asset Allocation Division of Fidelity Investments, specializing in global macro strategy and tactical asset allocation. He joined Fidelity in 1995 as a technical research analyst.

This is original content from Fidelity Investments in the U.S.

Endnotes

1 The source of all factual information and data on markets, unless otherwise indicated, is Fidelity Investments.

2 The term “CRIC cycle” was coined by Morgan Stanley’s chief economist for Japan, Robert Feldman, in his 2001 research on Japan’s policy behavior following the end of the Japan bubble.

3 Source of all earnings growth and estimates in this report: Bloomberg Finance L.P., as of 8/14/18.

*****

Commissions, trailing commissions, management fees and expenses all may be associated with mutual fund investments. Please read the prospectus, which contains detailed investment information, before investing. Mutual funds are not guaranteed, their values change frequently and past performance may not be repeated.

Certain Statements in this commentary may contain forward-looking statements (“FLS”) that are predictive in nature and may include words such as “expects”, “anticipates”, “intends”, “plans”, “believes”, “estimates” and similar forward-looking expressions or negative versions thereof. FLS are based on current expectations and projections about future general economic, political and relevant market factors, such as interest and assuming no changes to applicable tax or other laws or government regulation. Expectations and projections about future events are inherently subject to, among other things, risks and uncertainties, some of which may be unforeseeable and, accordingly, may prove to be incorrect at a future date. FLS are not guarantees of future performance, and actual events could differ materially from those expressed or implied in any FLS. A number of important factors can contribute to these digressions, including, but not limited to, general economic, political and market factors in North America and internationally, interest and foreign exchange rates, global equity and capital markets, business competition and catastrophic events. You should avoid placing any undue reliance on FLS. Further, there is no specific intentional of updating any FLS whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise.

From time to time a manager, analyst or other Fidelity employee may express views regarding a particular company, security, and industry or market sector. The views expressed by any such person are the views of only that individual as of the time expressed and do not necessarily represent the views of Fidelity or any other person in the Fidelity organization. Any such views are subject to change at any time, based upon markets and other conditions, and Fidelity disclaims any responsibility to update such views. These views may not be relied on as investment advice and, because investment decisions for a Fidelity Fund are based on numerous factors, may not be relied on as an indication of trading intent on behalf of any Fidelity Fund.

Stock markets are volatile and can fluctuate significantly in response to company, industry, political, regulatory, market, or economic developments.

Foreign markets can be more volatile than U.S. markets due to increased risks of adverse issuer, political, market, or economic developments, all of which are magnified in emerging markets. These risks are particularly significant for investments that focus on a single country or region.

Please note that there is no uniformity of time among business cycle phases, nor is there always a chronological progression in this order. For example, business cycles have varied between 1 and 10 years in the U.S., and there have been examples when the economy has skipped a phase or retraced an earlier one.

Investing involves risk, including risk of loss.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

Diversification and asset allocation do not ensure a profit or guarantee against loss.

All indices are unmanaged. You cannot invest directly in an index.

Index definitions

S&P 500 is a market capitalization-weighted index of 500 common stocks chosen for market size, liquidity, and industry group representation to represent U.S. equity performance. • MSCI World ex USA Index is a market capitalization-weighted index that is designed to measure the investable equity market performance for global investors of developed markets outside the United States. • MSCI Emerging Markets Index is a market capitalization-weighted index that is designed to measure the investable equity market performance for global investors in emerging markets. • Shanghai Stock Exchange Composite Index is a market capitalization-weighted index that index tracks the daily price performance of all A-shares and B-shares listed on the Shanghai Stock Exchange. • Goldman Sachs Financial Conditions Index tracks changes in interest rates, credit spreads, equity prices, and the value of the U.S. dollar; a decrease in the index indicates an easing of financial conditions, while an increase indicates tightening. • The Euro Stoxx Banks Index is a free-float market capitalization-weighted index that covers 30 stocks of bank market sector leaders mainly from 12 eurozone countries: Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, and Spain. • JPM (JPMorgan) EMBI (Emerging Market Bond Index) Global Index tracks total returns for the U.S. dollar-denominated debt instruments issued by emerging-market sovereign and quasi-sovereign entities, such as Brady bonds, loans, and Eurobonds. • JPM Emerging Market Currency Index measures the currencies of 10 emerging markets against the U.S. dollar in nominal terms.

Third-party marks are the property of their respective owners; all other marks are the property of Fidelity Investments Canada ULC.

© 2018 Fidelity Investments Canada ULC. All rights reserved.

Copyright © Fidelity Investments