by Niels Clemen Jensen, Absolute Return Partners

I am the king of debt. I understand debt probably better than anybody.

Donald J. Trump

A grim-looking future for traditional investing

Let’s begin with the bad news. For reasons that are quite clear if you read the Absolute Return Letter on a regular basis, neither equities nor bonds are likely to deliver particularly attractive returns in the years to come.

My central forecast is an annual average inflation-adjusted return of 0-2% between now and 2050 on a global portfolio consisting of 40%bonds and 60% equities. In other words, an arch-typical traditional portfolio following the 60/40 allocation ‘rule’, which so many investors do these days,will deliver next to no returns, if I get things about right.

The two main ‘risks’ to my rather lacklustre forecast are (i) that the next stage of the digital revolution (automation, AI, etc.) will cause productivity growth to re-accelerate much faster than can be reasonably expected, and (ii) that commercialisation of fusion energy will allow us to produce all the energy we need at virtually no cost, which will obviously have an extraordinary impact on productivity.

I have spent most of the summer researching both (i) and (ii), and I am sure my findings will find their way into future Absolute Return Letters, but that is not my point here. Rather, I am going to urge you to think outside-the-box when constructing your portfolio because, if you don’t, the next many years could be rather painful. Today, I will look at the “40” in the 60/40 allocation rule. Are there ways to enhance the returns of the 40% that is allocated to bonds without adding substantially to risk?

The good news next. Fortunately, there are many things you can do to improve on those lacklustre numbers. Those returns are reserved for the lazy investor - someone who invests passively. Today, I will review one of the ‘escape routes’, should you desire higher returns - an investment strategy I call private credit.

There is admittedly a caveat you should be aware of. When you buy bonds (public credit), you are offered overnight liquidity, but that is not possible in private credit. The best terms we have come across offer quarterly liquidity, but the best yielding offerings will tie up your capital for several years.

Let me put some numbers behind what I just said. A bond portfolio consisting of equal measures of 10-year government bonds from Germany, France, Italy, Spain, the UK and the US offers an annual yield of about 1.6%, not taking currency fluctuations into account.

We act as advisers to an income fund that offers quarterly liquidity, and the yield on that fund hovers around 5% - sometimes a bit more and sometimes a bit less. However, we also have clients who are happy to go significantly more illiquid. At the most illiquid end of the scale - 6-7 years of no access to your capital - annual yields of 7-8% are perfectly normal.

You may need (near) instant access to your capital and, if that is the case, the opportunity set may be limited. I should also point out that some investors are not deemed sophisticated enough to invest in certain types of investment products. For all those investors, private credit may be a no-go.

Compliance with MiFID II

There is one more point to be addressed before I start. New rules were recently implemented to regulate the distribution of research (the so-called MiFID II rules). Under the new rules, we cannot publish what is deemed to be research to non-clients of the firm.

The Absolute Return Letter is classified as non-research, as long as I adhere to a set of relatively simple rules, so that’s all fine. However, in this month’s letter, I discuss a specific opportunity set in private credit, which is admittedly akin to sailing a bit closer to the wind than I would normally do.

For that reason, in the following, there is no mention of any investment opportunities within the various credit strategies that I bring up, and I offer no opinions.

What is private credit?

Private equity is a well-established term that rarely confuses industry observers. Even my parents’ dog knows what private equity is, although that dog is admittedly quite smart.

Private credit is a different story. When a business associate of mine asked me the other day what I thought of private credit, I (sort of) knew how to respond but, to be on the safe side, I looked up how the term is actually defined. According to AIMA, private credit is:

“…credit that is extended to companies or projects on a bilaterally negotiated basis. It is not publicly traded such as many corporate bonds and is originated or held by lenders other than banks. It takes various legal forms including loans, bonds, notes or private securitisation issues.” (Source: AIMA on Private Credit)

So far so good. In one important aspect, my definition of private credit varies from the mainstream definition, though. Whereas most investors use the terms private debt, private credit and direct lending almost interchangeably, there is much more to the private credit story than ‘just’ lending as I see things.

As per my definition, private credit includes all non-public transactions conducted away from banks, where one party owes a sum of money to another party, whether that liability is the result of lending or otherwise. That “otherwise” would include leasing transactions, royalties a.o., and the investment universe that can be taken advantage of is therefore bigger.

In the following, I will stick to my definition. As long as a transaction involving an element of credit takes place between two parties, and as long as that credit is non-public in nature and originated away from banks, I will happily categorise it as private credit. Whether that credit takes the form of lending, leasing or something entirely different matters little to me.

Why private credit is growing so fast and why the growth will continue

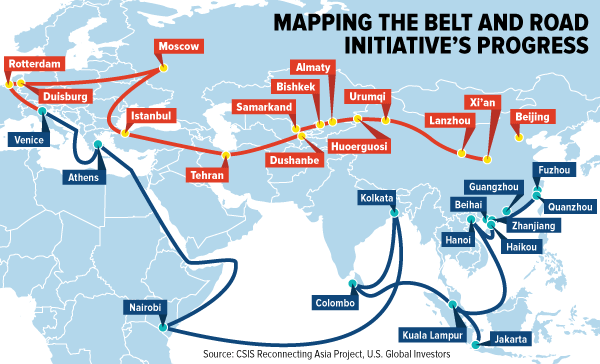

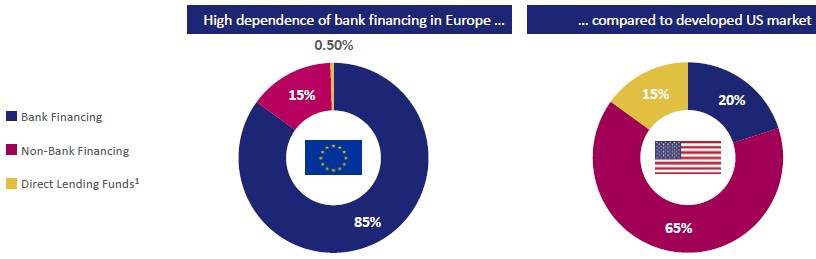

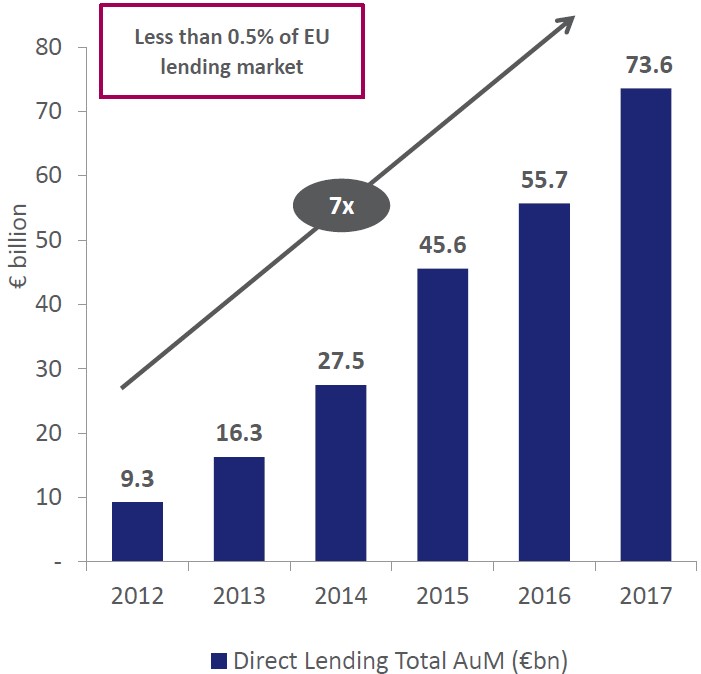

Post 2008, ever more lending (and other types of credit) has been originated away from commercial banks although, up to this point, direct lending has grown much faster in the US than in Europe (Exhibit 1).

Source: BlueBay AssetManagement (2016 data)

Note: Exhibit 1 includes direct lending only, which is only a subset of the asset class that I define as private credit.

Although the direct lending market in the EU is minuscule when compared to the US (as is obvious when looking at Exhibit 1), it continues to grow rapidly (Exhibit 2).

There are at least a couple of reasons why that is. At the very highest level, the loan books of European banks are dramatically bigger than those of US banks, and that has forced European banking regulators to draw a line in the sand.

For two economies that are not that different size-wise, it is remarkable that the loan books of EU banks are more than twice the size of those of US banks. Although no target has been officially declared, I happen to know that European banking regulators are determined to bring European loan books down, so that they are more in line with those of US banks.

Many industry observers I have spoken to think that whilst this is an opportunity for the short term, banks will eventually come roaring back. I am not so sure, as the logic behind that argument simply doesn’t hold water.

The argument goes as follows:

Banks all over Europe (and elsewhere) are busy preparing themselves for new capitalisation rules, about to be enacted by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). The new rules will come into effect in March 2019 and are known as Basel IV. Consequently, banks must improve their capital ratios (i.e. aim for more equity-to-debt) between now and then.

Source: BlueBay Asset Management (2016 data)

However, once we have passed March 2019 (or so the argument goes), banks will be back in full swing but, if my source is correct, the regulatory pressure on banks to slim down will continue for a long time to come. In other words, private credit will likely continue to grow, and it will grow faster in Europe than elsewhere.

The other point worth mentioning is the growing bureaucracy within banks. It is not unusual, when a corporate borrower applies for a loan, that the credit department within the bank takes months to decide whether to say yes or no.

Private credit providers, on the other hand, typically take no longer than 1-2 weeks to respond to such requests. In today’s environment, where most corporates face global competition, waiting 2-3 months for the bank to return your phone call is simply not good enough.

It is also worth noting that even if the private credit provider takes almost as long as the bank to make its mind up (and some do), almost all of them still offer far more structuring flexibility that banks are prepared to.

Various private credit strategies

If you get as many silly emails as I do, I am pretty sure you have also received the occasional email, promising you 20% or even higher returns on (for example) peer-to-peer lending. However, in this context, I will exclude those types of offerings, as I want to compare apples to apples - i.e. respectable private credit strategies to corporate bonds or bank lending.

Respectable private lending won’t generate 20%+ annual returns, although a few get pretty close, particularly if you are prepared to also accept an element of equity risk. Furthermore, given the returns on offer in most bond markets these days, even if you don’t want to go too far out the illiquidity curve, returns on private credit are still attractive.

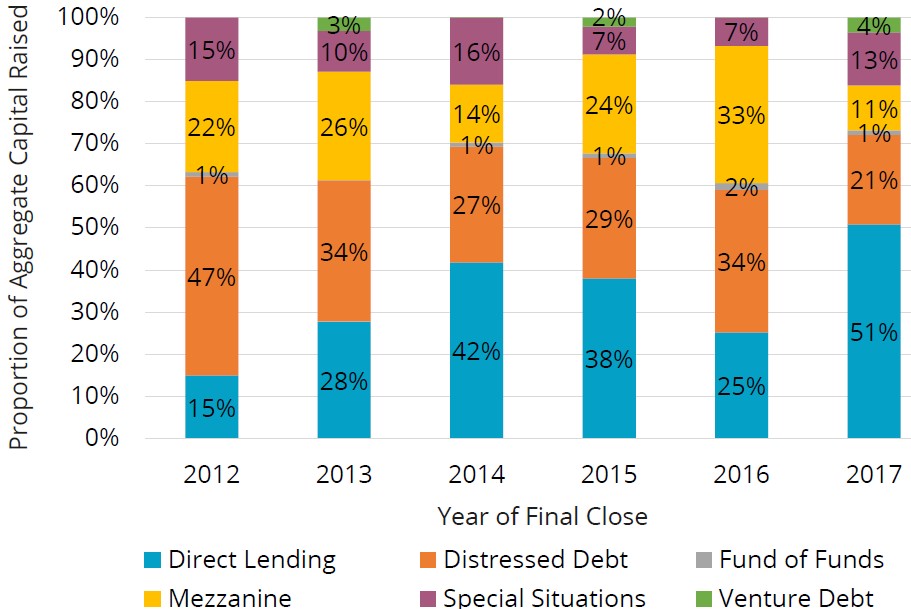

Within private credit, Direct Lending is undoubtedly the sub-strategy that has attracted the most capital from investors in recent years (Exhibit 3). Preqin’s (Note: Preqin is the alternative asset industry’s leading source of data and intelligence) analysis in Exhibit 3 doesn’t include some of the investment strategies that I would include in private credit; i.e. one could argue that Exhibit 3 doesn’t provide a full picture.

Source: 2018 Preqin Global Private Debt Report, Preqin Online

Having said that, as the strategies I would include are relatively small compared to most of the strategies included by Preqin, my conclusion still stands.

Returns generated by Direct Lending funds vary quite a bit depending (amongst other things) on the credit rating of the borrowers, the seniority of the underlying loans and the use of leverage by the investment manager in question.

That said, in my experience, mid-to-high single digit returns (net to investors) are quite common when providing plain vanilla working capital to mid-sized corporates, which would be the bulk of the Direct Lending funds included in Exhibit 3. And that can go as high as mid-teens when things are not so vanilla (e.g. mezzanine debt or special situations).

Regulatory Capital Relief is a derivative of plain vanilla lending. You also invest in a portfolio of loans when you invest in this strategy, but only indirectly. The investment manager and a bank of his choice will enter into a deal, whereby investors in the reg. cap. fund underwrite a portion of potential future losses of the bank’s loan book in return for a coupon.

In doing so, the bank’s capital position is improved, making it an integrated part of its ability to comply with Basel IV. Think of Regulatory Capital Relief as re-insurance. As many banks are struggling to get ready before the March 2019 deadline, extraordinarily attractive terms are currently on offer. Returns generated in this investment strategy are (on average) modestly higher than those of direct lending strategies, while the risk is usually lower.

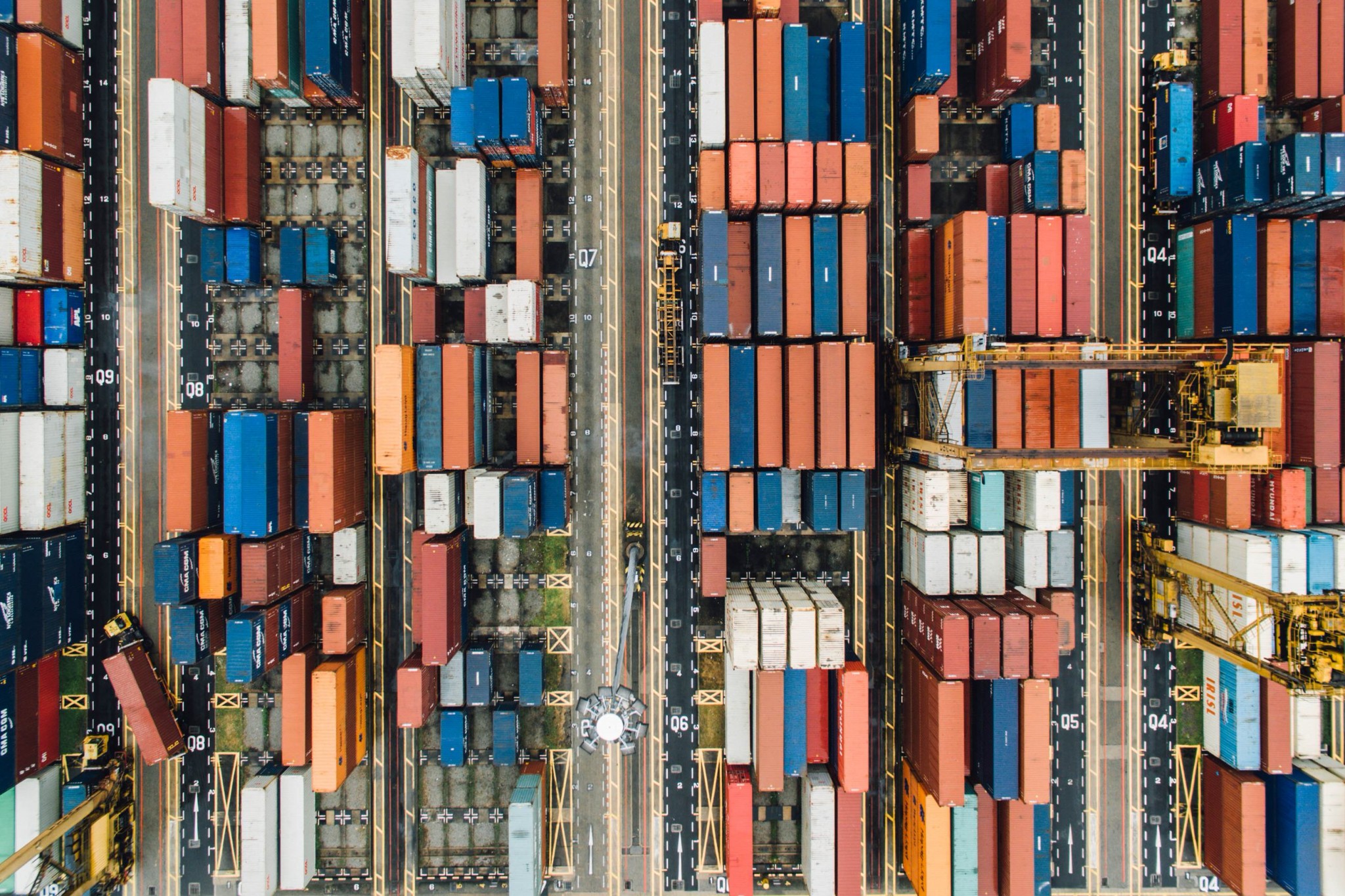

Trade Finance is another private credit strategy that has grown massively more recently (not included in Exhibit 3). Before 2008, commercial banks had virtual exclusivity on this market, but the rising bureaucracy in the banking sector has moved a substantial part of it into the hands of alternative lenders.

If the manager of a banana plantation in Zambia wants to secure export finance for a shipment of bananas to a UK supermarket chain, he can hardly wait 2-3 months for his bank to approve the credit application, can he?

Trade Finance can be either import or export related, and there is almost always an emerging market (EM) domiciled company on at least one side of the equation. Annual returns vary depending on region (mostly Africa, Asia and South America) but are typically in the 5-10% range. The risk is relatively low, and liquidity terms usually amongst the best in the private credit space, as the financing is mostly short-term in nature.

There are indeed (many) other lending strategies on offer (e.g. CLO Warehousing, Receivables & Factoring, Real Estate Lending, Peer-to-Peer Lending and Multi-Strategy Lending) but I will switch to leasing now.

In the leasing space, you can (amongst other things) invest in Railcar Leasing, in Container Leasing and in Aviation Leasing, the latter of which is the leasing strategy we have done the most work on. If you think of it, from an airline’s point of view, there is great economic logic to leasing rather than buying the aircraft you need to service your customers.

Owning your fleet of aircraft ties up an awful lot of working capital; it reduces your flexibility when you want to downsize during difficult times, and new routes cannot so easily be tested with smaller aircraft before switching to bigger ones, assuming the new route is successful.

When I first joined the financial services industry in 1984, less than 5% of all commercial aircraft were leased. Today, the equivalent number is above 40% - a testament to airlines’ desire for more flexibility. Annual cash yields are typically in the 7-9% range and total returns well above 10%.

The difference between those numbers is accounted for by the exit value of the aircraft when it is eventually sold, mostly represented by the value of the engines. Remember - the engines on a 20-year old aircraft are only a few years old, as every single part is renewed regularly.

Royalties next. Royalties is a surprisingly comprehensive investment strategy with offerings in areas as widespread as Intellectual Property, Mining, Energy, Pharmaceuticals, Science & Tech as well as Music Royalties, the latter of which has attracted most of our attention so far.

The reason is simple. Unlike most other investment opportunities (whether companies or funds), which have been negatively affected by disruption, Music Royalties have actually benefitted.

Most consumers don’t buy CDs anymore – they stream instead. Falling CD sales have not affected royalty streams as much as you would have thought, as CD sales are not always subject to royalties. Rapidly growing streaming, on the other hand, has doubled the growth rate of music royalty streams, as streaming generates plenty of royalties. It is one of very few investment strategies that have benefitted from disruption without it being the disruptor.

I could carry on for another few pages, but you probably get my point by now. The opportunity set in private credit is vast. When we construct portfolios of this nature for our clients, three of the most important (but not the only) variables are:

- the appetite for illiquidity;

- the appetite for cyclicality; and

- the appetite for correlated returns.

If you run a very traditional portfolio, the returns being generated by the bond/credit component will be nearly 100% correlated to the returns of the broader bond and credit markets.

Depending on your appetite for correlated returns, and your appetite for the other variables just mentioned, the portfolio construction will be affected, but so will expected returns. You cannot have the cake and eat it!

The key risk associated with private credit

Most risks associated with private credit are simply a repeat of the risks you are exposed to when investing in public credit (borrower quality, cyclicality, quality of collateral, etc.). Since those risks are all well understood, I will spend no further time on them.

The one risk factor that is far more prevalent in the private than the public space is the potential mismatch between assets and liabilities. Again and again, I come across investment managers within private credit who offer (sometimes substantially) better redemption terms to their investors than the underlying credits justify. How can you possibly offer your investors quarterly redemption terms, if the tenor of the underlying credits average 5-6 months, and some extend into years?

These investment managers depend on the benign conditions we currently enjoy to last forever but, as I have learned over the years, they never do. Although the Global Financial Crisis of 2007-09 was admittedly worse than anything we have seen for more than half a century, I learned (the hard way) never to underestimate the amount of damage even a modest mismatch between assets and liabilities can inflict.

Concluding remarks

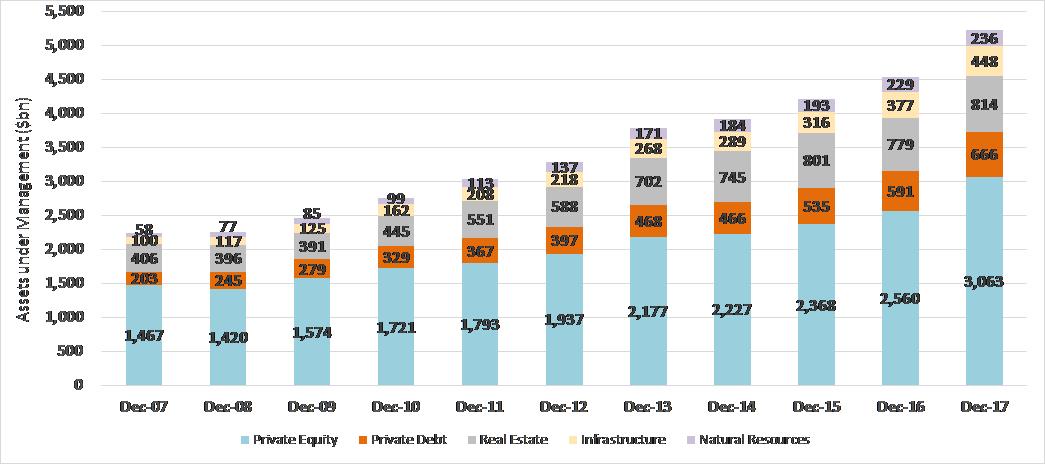

Whether you define the asset class more narrowly as Preqin does, or you define it more broadly as I do, fact of the matter is that most of the sub-strategies in private credit are still relatively small (Exhibit 4), limiting the opportunity set for the biggest investors of this world.

There are examples of private credit strategies that can deploy vast amounts of capital, Direct Lending being the most obvious example, but the opportunity set is most definitely bigger for smaller investors.

Let me give you an example of how things work. At Absolute Return Partners, before we invest in anything, we spend at least 3-4 man-months on researching the opportunity in question. As the Managing Partner of the business, I will simply not allow one of our research analysts to spend the next several months researching an investment candidate if the economics don’t add up.

Source: Preqin

(Note: Preqin defines Private Capital as the broader spectrum of private, closed-end funds)

You cannot blame the largest investors for thinking along those same lines. If a £100 billion pension fund (and there are quite a few of those) can only put 0.05% (or less) of its assets into a given strategy, even if the investment does extraordinarily well, the needle will hardly move. In other words, it is perfectly rational for some of the very large pension funds to pass on many of the private credit strategies. You don’t spend 3-4 months on something that doesn’t move the needle. Smaller investors, on the other hand, are not constrained by such issues, and that will be a major competitive advantage in the years to come.

Niels C. Jensen

3 September 2018

Copyright © Absolute Return Partners