by Lance Roberts, Clarity Financial

“Only those that risk going too far can possibly find out how far one can go.” – T.S. Eliot

I was reminded of that quote recently as I was reading a great piece by Tim Duy:

“Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell took to the podium at the annual Jackson Hole monetary conference, delivering a message of support for the central bank’s policy of ongoing gradual interest-rate increases. This policy stance is less about commitment to estimates of key policy variables such as the natural rate of interest and more about data dependence. Unfortunately, Powell left the unsettling feeling that monetary policy can be summarized as ‘We plan to keep hiking until something breaks.’”

Tim makes a great point.

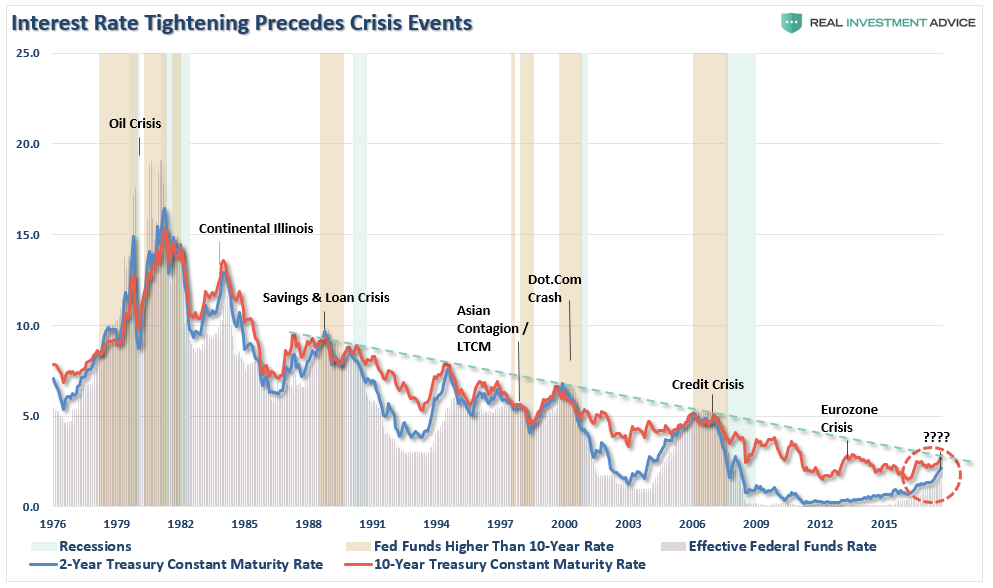

I have spilled a lot of digital ink discussing the problems with monetary policy in the past, and in particular, with the Fed’s rate hiking campaigns. The results have always been, without exception, either poor or disastrous.

“In the U.S., the Federal Reserve has been the catalyst behind every preceding financial event since they became ‘active,’ monetarily policy-wise, in the late 70’s. As shown in the chart below, when the Fed has lifted the short-term lending rates to a level higher than the 10-year rate, bad ‘stuff’ has historically followed.”

The same applies to stock market investors as well. As I wrote previously,

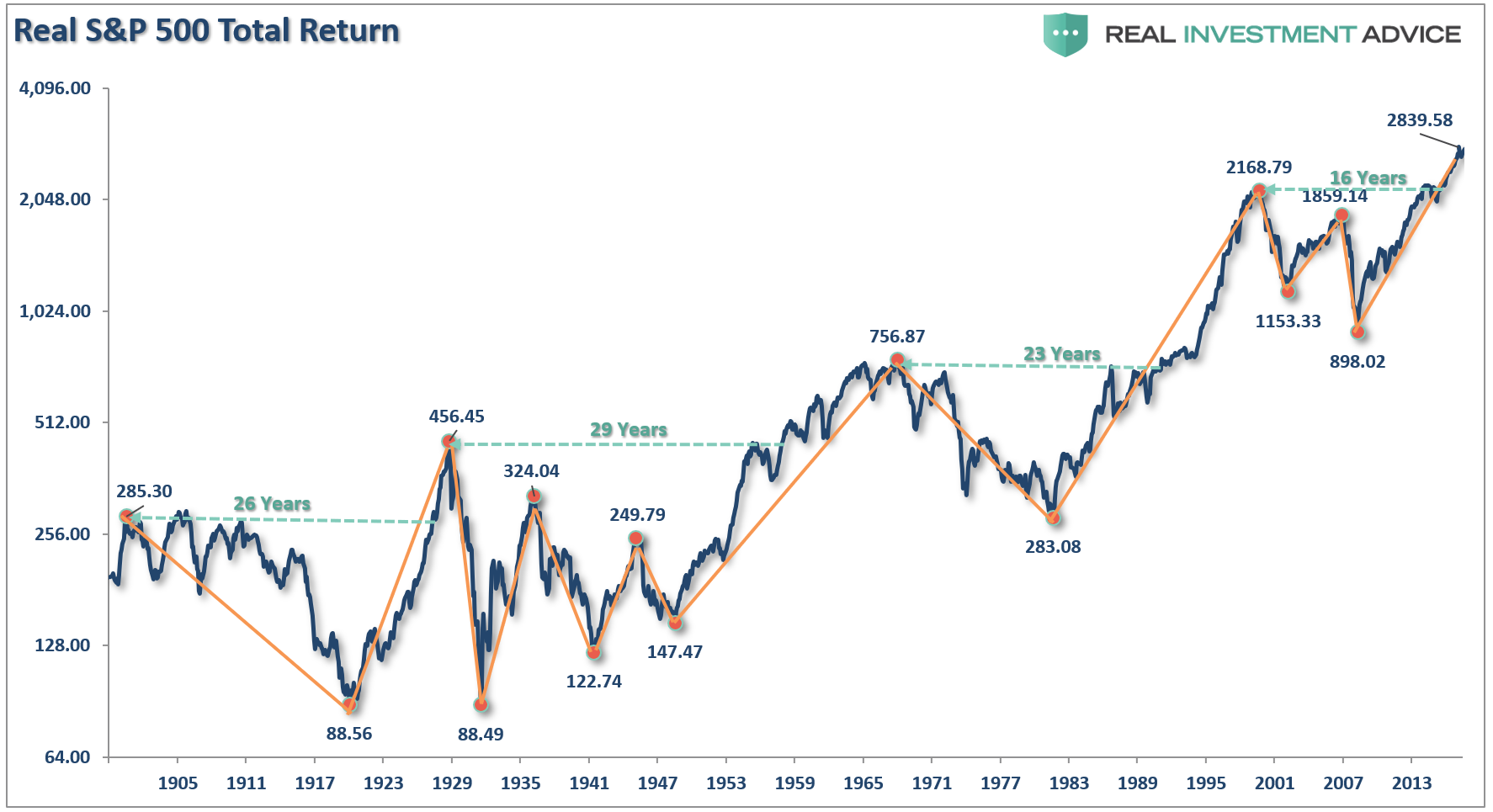

“First, “record levels” of anything are records for a reason. It is where the point where previous limits were reached. Therefore, when a ‘record level’ is reached, it is NOT THE BEGINNING, but rather an indication of the MATURITY of a cycle. While the media has focused on employment, record stock market levels, etc. as a sign of an ongoing economic recovery, history suggests caution.”

In the “rush to be bullish” this a point often missed. When markets are hitting “record levels” it is when investors get “the most bullish.” Conversely, they are the most “bearish” at the lows.

It is just human nature.

“What we call the beginning is often the end. And to make an end is to make a beginning. The end is where we start from.” – T.S. Eliot

Despite the best of intentions, a vast majority of the “bullish” crowd today have never lived through a real bear market. You know such is true when you read a comment like this:

“What all equity investors need to do — is to be mentally prepared for a temporary (maximum 2 year) 33-50% drop. 90% drops like the Great Depression aren’t going to happen ever again. You may have a 50% drop but it will come back in two years max.”

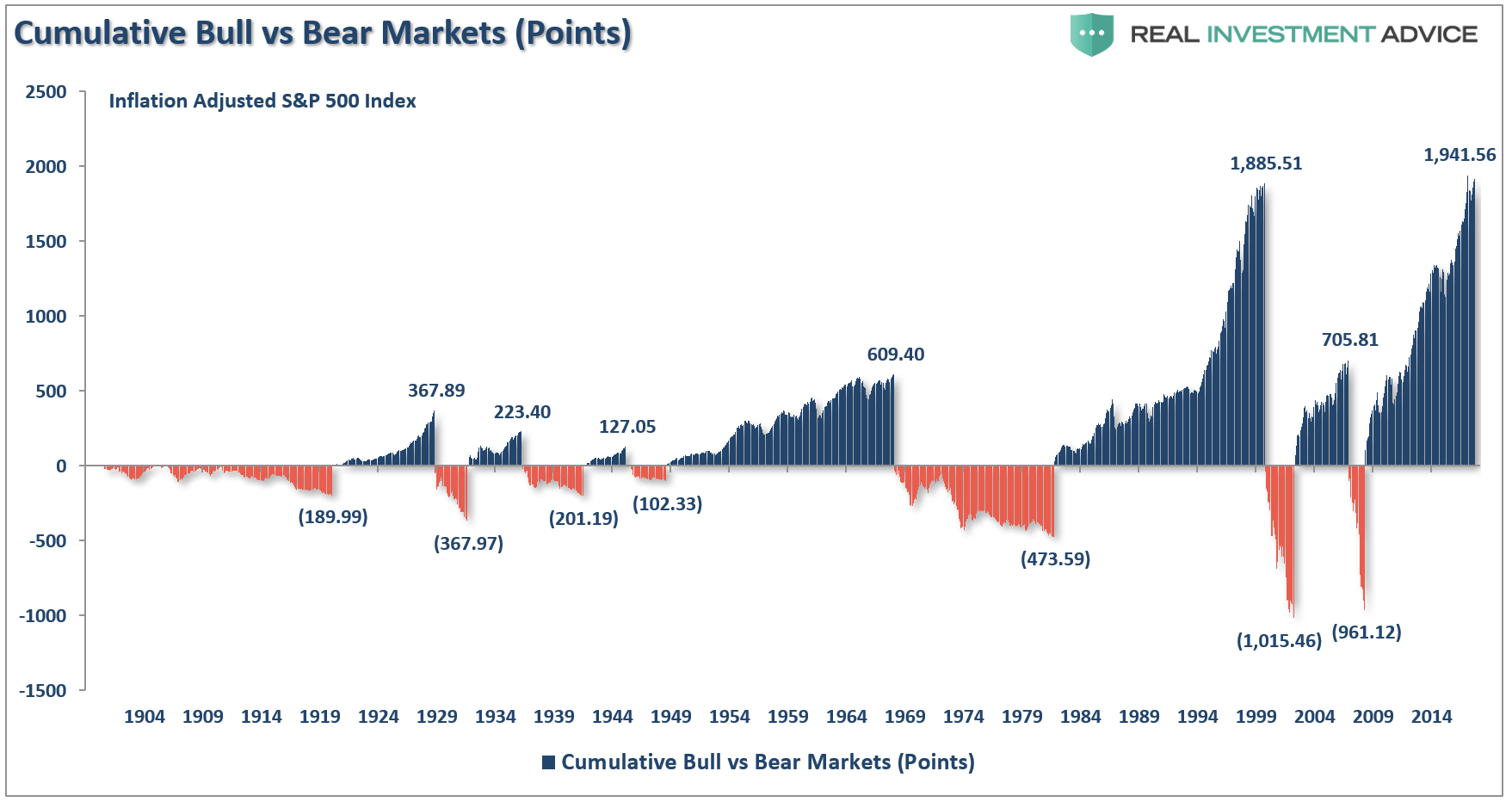

Two charts show the ignorance in that statement.

Bull markets, with regularity, are almost entirely wiped out by the subsequent bear market.

Another comment showed equal ignorance of market dynamics.

“A common fallacy is that ‘every bullish trend results in an equally bearish trend,’ or that bull and bear market seesaw EQUALLY, like yin and yang. But nothing is further from the truth. Bull Markets last 6 TIMES LONGER and rise 10 TIMES HIGHER than bear markets do.”

Yes, they do seesaw and, for the most part, are almost always equal in nature. (a 100% gain and 50% loss are the same thing) For every bull market, there will be a bear market. But, as shown above, it is clearly not the case that bull markets rise 10x higher than bear markets fall.

Market participants never act rationally. Neither do consumers.

The Instability Of Stability

This is the problem facing the Fed.

Currently, there is a very high level of complacency with a strong belief in the motto “The Fed can do no wrong.” Or should I say, there seems to be a very large consensus the markets have entered into a “permanently high plateau,” or an era in which price corrections in asset prices have been effectively eliminated through monetary policy.

Interestingly, it is that very belief on which the Fed is dependent. With the entirety of the financial ecosystem now more heavily levered than ever, due to the Fed’s profligate measures of suppressing interest rates and flooding the system with excessive levels of liquidity, the “instability of stability” is now the biggest risk.

The “stability/instability paradox” assumes that all players are rational and such rationality implies avoidance of complete destruction. In other words, all players will act rationally and no one will push “the big red button.”

Again, the Fed is highly dependent on this assumption as it provides the “room” needed, after more than 9-years of the most unprecedented monetary policy program in U.S. history, to try and extricate themselves from it. The Fed is dependent on “everyone acting rationally.”

As I noted in last week’s newsletter, Fed Chairman J. Powell is depending upon the everyone buying into the current narrative he provided:

“There is good reason to expect that this strong performance will continue. I believe that this gradual process of normalization remains appropriate.“

However, there are concerns about the durability of that backdrop as “everything is as good as it can get.”

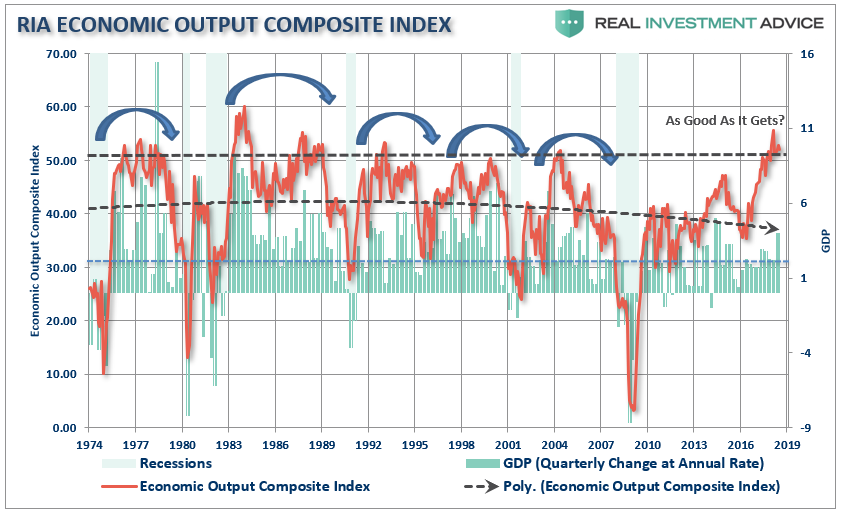

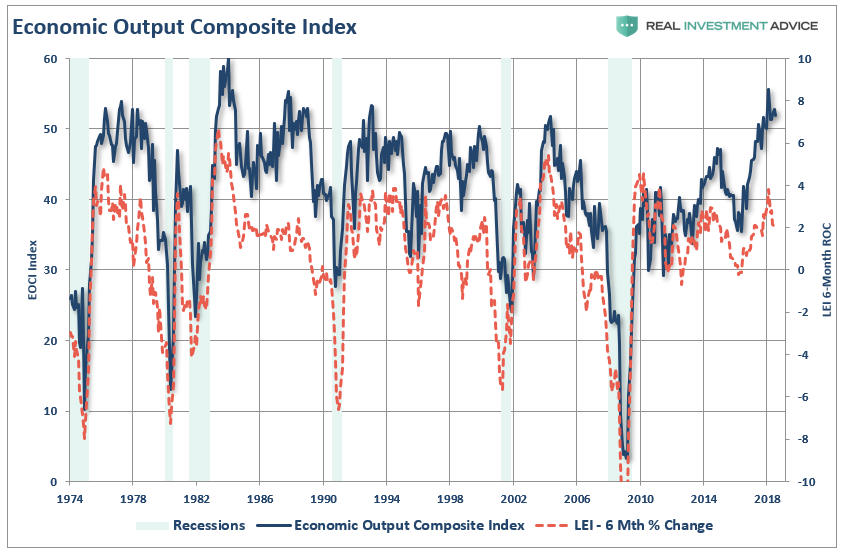

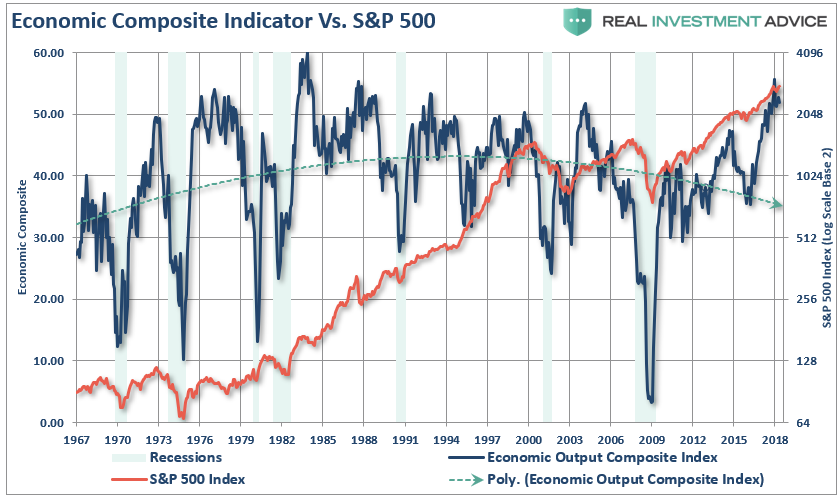

To understand this we can look at our own RIA Economic Output Composite Index (EOCI) which is an extremely broad indicator of the U.S. economy. It is comprised of:

- Chicago Fed National Activity Index (an index comprised of 85 subcomponents)

- Chicago Purchasing Managers Index

- ISM Composite Index (composite of the manufacturing and non-manufacturing surveys)

- Richmond Fed Manufacturing Survey

- New York (Empire) Manufacturing Survey

- Philadelphia Fed Manufacturing Survey

- Dallas Fed Manufacturing Survey

- Markit Composite Manufacturing Survey

- PMI Composite Survey

- Economic Confidence Survey

- NFIB Small Business Index

- Leading Economic Index (LEI)

All of these surveys (both soft and hard data) are blended into one composite index which, when compared to U.S. economic activity, has provided a good indication of turning points in economic activity.

Currently, the index has peaked from it’s second highest level on record. In every previous period where the index achieved current levels, it had been near the peak of that economic cycle.

It is also worth noting the 6-month average of the Leading Economic Index (LEI) has recently turned down and this index reliably leads the EOCI by a couple of months.

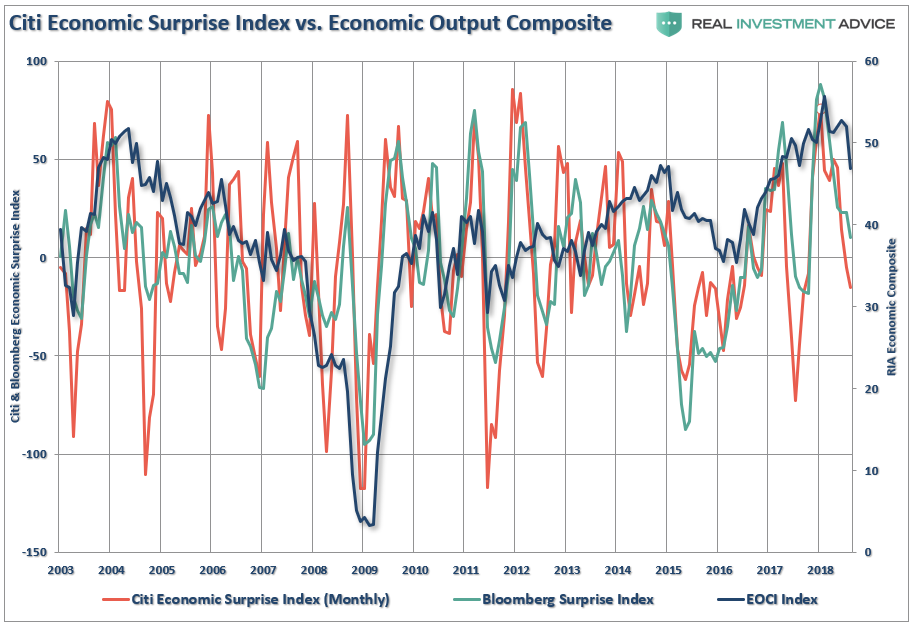

The Citi and Bloomberg Economic Surprise indices, which also tend to lead our EOCI have turned sharply lower following the recent “natural disaster recovery” surge from late last year. This was the point I made recently:

“But the cracks are already starting to appear as underlying economic data is beginning to show weakness. While the economy grinds higher over the last few quarters, it was more of the residual effects from the series of natural disasters in 2017 than “Trumponomics” at work. The “pull forward” of demand is already beginning to fade as the frenzy of activity culminated in Q2 of 2018.”

It is here we find the biggest potential risk for the Fed.

There are already signs that forward economic activity may be significantly weaker than currently expected. Yet the Fed is making policy decisions based on the current trend of activity. As Tim notes:

“This raises the bar for a pause. Powell and his fellow policy-makers need to see a definite change in the numbers that leads them to believe that economic activity has moderated and financial conditions have sufficiently tightened to justify the pause. In other words, they are not inclined to take a leap of faith and pause as they hit neutral to assess the impact of past tightening. They need to see a reason to stop tightening.”

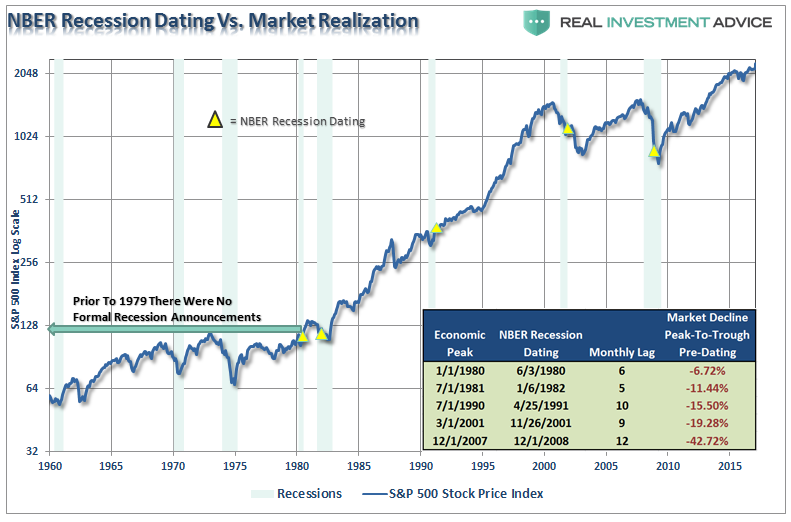

The Fed operates on current economic data as it comes in. However, all economic data is revised in the future, and when those revisions become sharply negative, the results aren’t good. For example, in December of 2007, no one believed the U.S. economy was in a recession. However, after a near 50% plunge in asset prices and the worst economy since the “Great Depression,” the NBER officially stated in December of 2008 the recession had started a year earlier. Such was not an outlier event, but rather the norm for NBER recession dating.

As Tim notes:

“The worst-case scenario is that something actually needs to break before the Fed stops tightening. This is a possibility because of the long and variable lags in the policy process. The Fed could keep on hiking well past when it should stop, or fail to reverse course quickly enough, because the data has yet to catch up with a slowdown already occurring under the surface. This is arguably how expansions end.”

I would disagree with Tim on the last sentence.

It should have read: “This is how expansions end.”

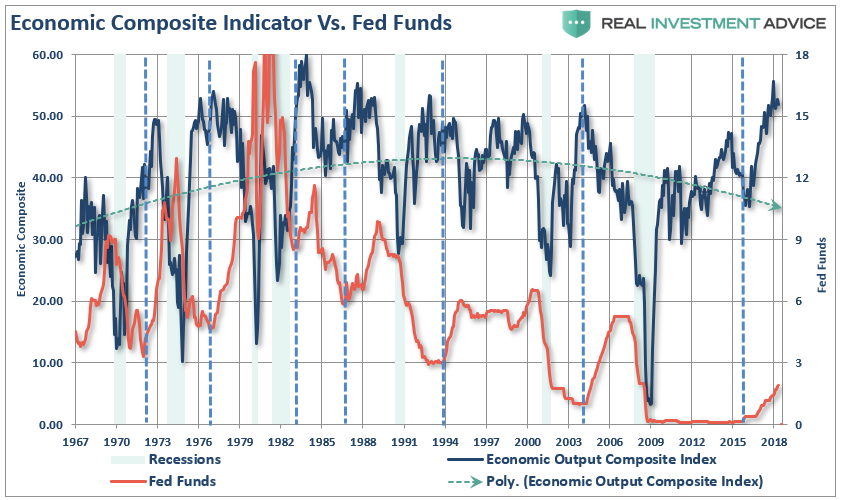

As shown below, when you overlay our EOCI index with the Fed funds rate, we see that every rate hiking campaign denoted the “beginning of the end” of every expansion period. Unfortunately, as Tim notes, by the time the data is revised, it will be well after the point at which the Federal Reserve should have stopped their rate hike campaign.

Unsurprisingly, when the Fed eventually “breaks something,” the downturns in the EOCI index also coincide with a stock market contraction as well.

The Single Biggest Risk To Your Money

All of this underscores the single biggest risk to your investment portfolio.

In extremely long bull market cycles, investors become “willfully blind,” to the underlying inherent risks. Or rather, it is the “hubris” of investors they are now “smarter than the market.” As Doug Kass recently noted:

“In reality, if one listens to the business media (presumably one of the guiding sources of investor opinion) there is little recognition of any negatives these days. There is, to most of the media, no ‘wall of worry’ at all. Here are a few of my concerns – not one of which was the subject of discussion in the business media today:

- Growing economic ambiguities in the U.S. and abroad: peak autos, peak housing, peak GDP.

- Political instability and a crucial midterm election.

- The failure of fiscal policy to ‘trickle down.’

- An important pivot towards restraint in global monetary policy.

- An unprecedented lack of coordination between super-powers.

- Short-term note yields now eclipse the S&P dividend yield.

- A record levels of private and public debt.

- Near $3 trillion of covenant light and/or sub-prime corporate debt. (eerily reminiscent of the size of the subprime mortgages outstanding in 2007)

What, me, worry?”

At the moment, there certainly seems to be no need to worry.

The more the market rises, the more reinforced the belief “this time is different” becomes.

Yes, everything certainly is “as good as it can get.”

But therein lies the single biggest risk to the Fed and your portfolio.

“Bull markets” don’t die of pessimism – they die from excess optimism.

Unfortunately, by the time the Fed realizes what they have done, it will be too late.

Copyright © Clarity Financial